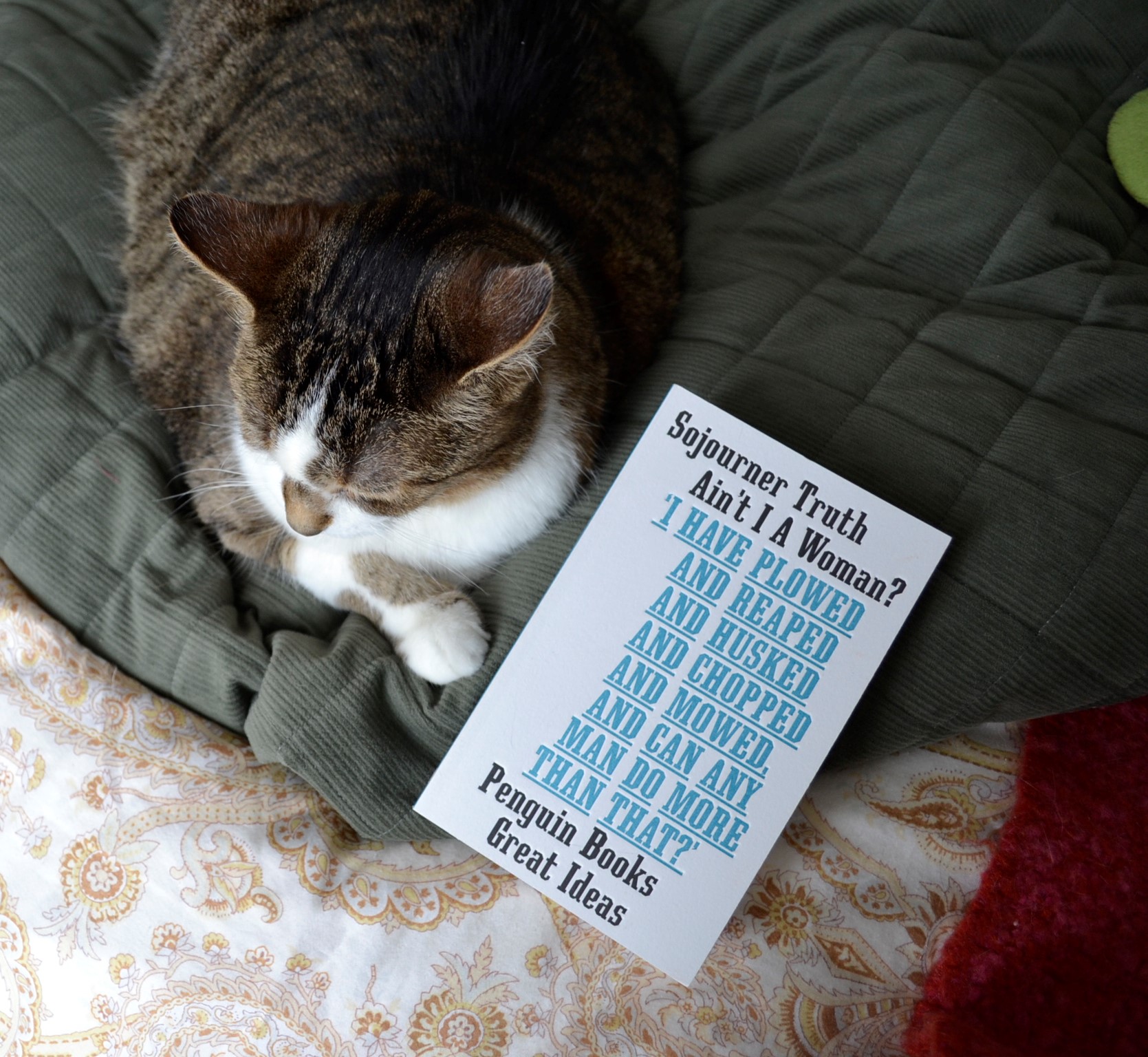

Ain’t I a Woman?

A modern reader will perhaps be struck by the religious bent of her speeches and arguments that hinge on some outdated ideas, but it’s important to realize that Truth was an essential starting point for the fight for equality for women and for suffrage. She was the beginning of the evolution of what that fight became and how it continued.