A Long Read Need Not Be Many Pages

I’m going to admit it right off the bat, Doctor Faustus (Doktor Faustus) is not an easy read. For the first three hundred pages it is a difficult slog up an impossible mountain that one cannot see the peak of. Rarely does writing make me cry with frustration. In fact, I cannot think of any other book that has made me leak bitter tears of ‘where in the name of all things sacred does this interminable philosophical conversation end?’

I’m going to go ahead and warn you that you need to invest 300 pages in this book before you start to gain your footing. It will be difficult. It will be frustrating — especially considering that the book in its entirety is not much more than 500 pages in total. It will also take you a long time. Normally, I can finish a book of this length in a few days or, at most, a week. I had to take a week-long break from reading this one which brought my total reading time to a bit inside of a month.

It was very difficult but, when I look back on it, I can’t say that it was a bad book. Mann meant it to be challenging and to challenge your idea of how a novel progresses and what you can hope to get from it as a reader. You need to be able to read the words on more than one level and be willing to be patient in order to reap the rewards of Doctor Faustus.

Not a ‘beach read’. Not that anyone would be likely to make that mistake.

A Comparison to Goethe

The first Faust I read was Goethe’s, and Mann’s Doctor Faustus draws on Goethe’s work. Both novels feature a deal with the devil, and both end with the main character’s realization and regret at the choice they made and the consequences of it.

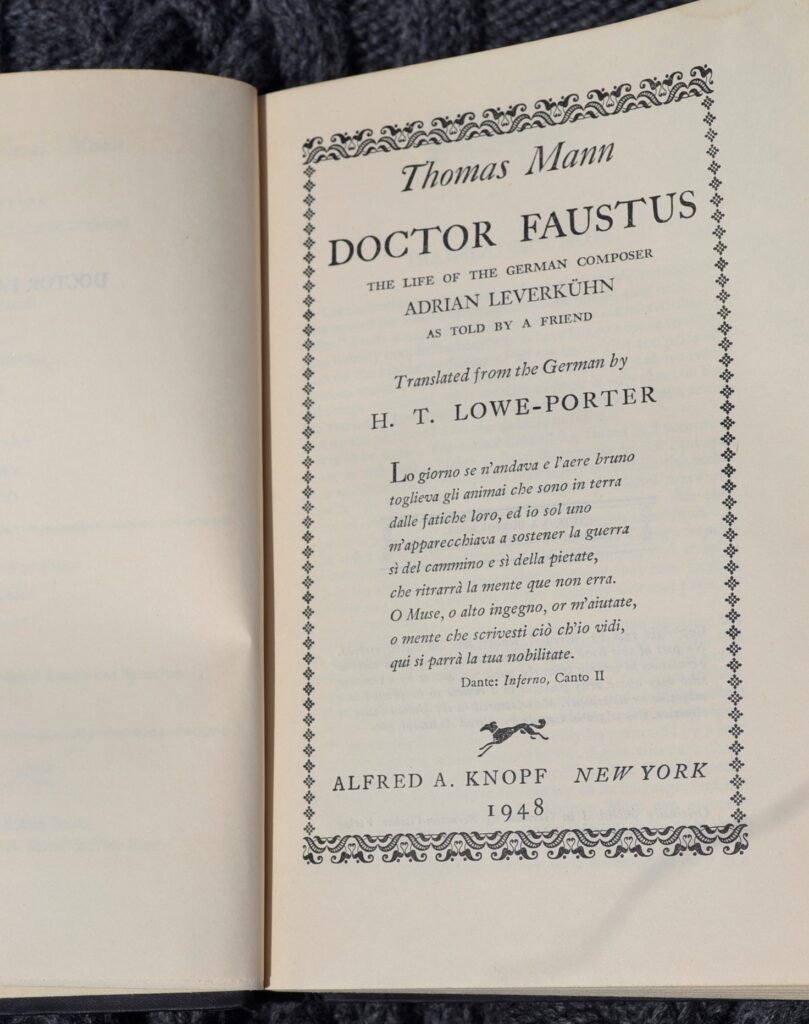

Mann’s Doctor Faustus is the account of one Serenus Zeitblom who is writing a biography of his childhood friend Adrian Leverkühn. Leverkühn becomes a composer, but makes a bargain with the devil. For twenty-four years of creative genius, he trades his soul — or, more specifically, his ability to love.

Leverkühn’s bargain can be interpreted as both literal and metaphorical. There is an account of him speaking to the devil, yes, but the reader can never be sure whether this happened or whether he has dreamt the event. Or if the devil he is describing is his own intentional contraction of syphilis and the degenerative aspect of the disease.

Either way, Leverkühn is a solitary figure lost in his craft as those around him suffer through the perils of the time, and those closest to him — including the narrator — fail to really know him at all. Those that he has any affection for meet a series of tragedies.

An Ode to Music, Academia, and The Arts

Doctor Faustus is without a doubt Thomas Mann’s ode to his love of music. Music, musical theory, instrumentation, and history are detailed extensively and woven into the core of the plot. I have a bit of a background in music. I’ve taken a few courses in university and I used to play piano and clarinet, but in no way do I know enough about music to appreciate the amount of description that Mann puts into this aspect of the novel. It wasn’t inaccessible per se, but I did feel like I could only scratch the surface of several parts of the books because I didn’t have the education to get at any of the deeper facets.

However, I do have experience in working within academia and the arts, so those parts of the novel were familiar. Mann describes the salon culture and social habits of the intellectual class of this time. He goes into student culture as well. There are lots of written discussions of philosophy, theology, art, and culture. Some of the discussions are more engaging than others, but in general, the novel provides a good basic understanding of how salons worked and the kind of talk that members of one could expect at a gathering.

Concerning Post-War Germany

In a lot of ways, Doctor Faustus is also Thomas Mann’s discussion of WWII and the nihilism that swept German intellectual circles. Through Zeitblom, Mann questions the guilt of the everyday German for the actions of the German state. If the intellectual class should have seen what was coming and would it have been possible to stop it. He expresses disgust at the idea that what happened was seen by some as inevitable.

Through Adrian Leverkühn, Mann mirrors the corruption, deception, and ultimate collapse of Germany. He sees the country at first wrapped up in an arrogant, blind nationalism that dissolves into a craving for destruction and war before sinking into the depths of horror, suffering, and wanton violence before at length becoming an empty shell labouring under the shame of what it has done.

Mann conducts this exploration in a masterly way that gives the reader lots of room to think about what he is saying at the same time as the way he is choosing to say it. Like all post-war literature, Doctor Faustus struggles with both the war and its horrors as well as its aftermath and who should bear guilt for its travesties. And again, like most post-war literature, it doesn’t arrive at an easy or complete answer.

The Cost of Genius

The cost of genius is a theme that literature returns to time and time again — and for a reason. It’s a complex question of sacrificing for art, but not sacrificing humanity. Also there is a question of what art is and whether it can be defined by what is commercially successful.

Part of being in the arts is constantly searching for and trying to define the nature of it. It is also the constant quest to produce something that both is commercially successful and artistically meaningful. As a writer, I’m always thinking about writing, about literature, about how to push my work further while at the same time chisel out a career.

Leverkühn searches for the same things in regards to his music, but in the end sacrifices his soul for lasting impact and genius. Mann is making the point that the price he pays is far too high. That without a soul, his work is not his work at all. It is merely the devil’s notes written by his hand.

Perhaps Not the Best Start

As I was having such a difficult time with this novel, I did what I usually do when I feel like I’m struggling with a book. I went to the internet and figure out if other readers struggled as well. The answer was an emphatic yes.

I do have several works of Thomas Mann’s in my library and apparently I chose his most difficult novel to start with. Well, that probably wasn’t the best choice, but I can at least look forward to an easier read next time I chose pluck one of his books from the shelf.