Portraits and 18th Century Authors

The back flap of a modern hardcover book usually has the typical blurb and the typical author photograph. Sure, there are some variations on the typical picture — faces obscured by a sweater, the inclusion of a copious amount of houseplants, or pets, but, by and large, readers know what to expect.

As someone who reads classical literature — a lot of which was around before cameras were common or in some cases existent — instead of photographs, I see a lot of author portraits when I do research. They also fall into a usual pattern. Dark background, white powdered wig, stoic expression. Yawn.

But then you see Laurence Sterne’s portrait. The expression! The eyebrows! The stance! The hand on the hip! The portrait itself is almost as hilarious as Tristram Shandy. Whenever I read a work from the 18th century, I automatically think of this portrait.

And usually I laugh out loud no matter where I am, and that probably looks very strange.

The Birth of the Novel

The 18th century was the time of the birth of the novel as we now know it and is populated by writers such as Fielding, Sterne, Richardson, and Defoe. Reading work from this time is like reading the process of writers trying out techniques in a quest to determine what form a novel could or should take. What should a novel be?

There are experiments in form and pacing. Metaphor and allegory. You can see the influences of the other arts — many of which were going through similar developments. In Fielding’s work, the reader can obviously see the influence of the theatre. In Richardson, the influence of letter writing practices and correspondence. There are a hundred other examples.

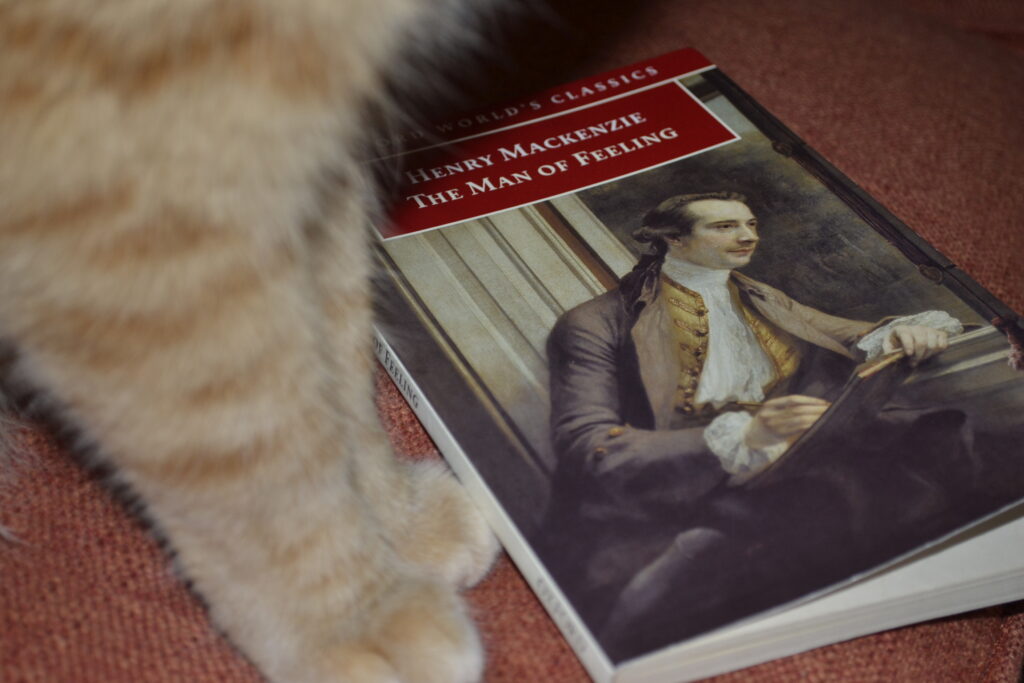

It was also a time when novels became wild successes. One of these successes was Henry Mackenzie’s The Man of Feeling. It was so successful that Mackenzie was still discussing it years later and publishing appendices for it. Additionally, it enjoyed popularity into the Victorian era as well.

The Man of Feeling

In form, The Man of Feeling is a novel that is set to mimic a ‘found’ manuscript, meaning that it is incomplete and starts in the middle as opposed to the beginning. It is also fragmentary in nature and can be understood best as a collection of vignettes on the theme of modern life and the place of sentimental feeling in modern behaviour.

Unlike other writers of the time, Mackenzie does not shy away from the political and social controversies happening around him. He discusses ideas of education and the European-tour-as-educator concept, dubbing it as trip the young go on to procure myriad new fancy snuffboxes. He also talks about the economy and the colonization of India and its governance.

At the same time, Mackenzie also uses The Man of Feeling to talk about the perils of city life and the modern age, lamenting the fact that card sharpers and con men abound, ready to take advantage of those that want to think the best of their fellow man. He both warns against thinking too much with sentimentality over common sense, but at the same time mourns that he has to give such a warning to the well-meaning.

Is This Satire?

Unlike Sterne or Fielding, Mackenzie’s satire is not as obvious nor quite as humorous. Yes, there are parts of the novel that are funny, but for the most part the text is tempered by what I would call a profound disappointment. Mackenzie is disappointed with the times he lives in and is disappointed that at this point in history those that believed in taking people at their word and being kind were mocked as being sentimental and naïve.

Mackenzie pokes fun at the protagonist Harley’s propensity for tears and foolish lack of insight into other characters’ motives and true personalities. But, at the same time, the author clearly wishes that one didn’t have to be so guarded and could trust people to be truthful and act morally. Mackenzie also clearly didn’t think much of London or of the practices of the modern age.

He longed for a simpler time that I’m not convinced ever truly existed. Every era and every person’s experience of modernity is full of good and bad. The problems change with the time period, but there just are never going to be less of them. All we can hope for is that there aren’t more.

A Vicarious English Degree

My lovely spouse is the one that introduced me to the works of the 18th century. Her degree is in English and, when we were in university, I got to hear about what she was studying. I listened with rapt attention and, though my studies didn’t leave me a whole lot of spare time, I wanted to read every book she was reading. I wanted to discuss them all with her.

Now that we’re long out of school and I’m helping her with her business, I finally have the time to catch up with all that reading I wasn’t able to do with her years ago. And my spouse is just as excited as I am to share it all with me.

There are a few things I have yet to catch up on — notably Richardson’s Clarissa — but I know that my spouse will be eagerly waiting with a warm cup of tea and an hour or more of conversation with every book I do finish.

[…] have mentioned Laurence Sterne’s famous portrait before, but I think now is the time to actually talk about his magnum opus and how I came to read […]