The Rise of the Little Birds

I’ve had a lot of blue jays coming to the feeder and pigging out on peanuts, but in the last few days the littler birds have started to make their presence known as well. The chickadees are battling the big blue feeder hogs for a share of the peanuts, and the dark-eyed juncos are hopping around the porch in greater numbers, chirping amongst themselves and twittering to the cats who are safely behind the door. Then you add in the mourning doves on the birdbath that try to pick up every stray bit of millet.

It’s extra magical to see the large variety of birds after we had a combination of snow and rain yesterday then another sharp taste of the winter to come this morning when I had to break up the ice in the frozen birdbath. I love this slow transition to the snowy season, but I know it can be difficult on the wildlife — especially when the temperature fluctuates so much.

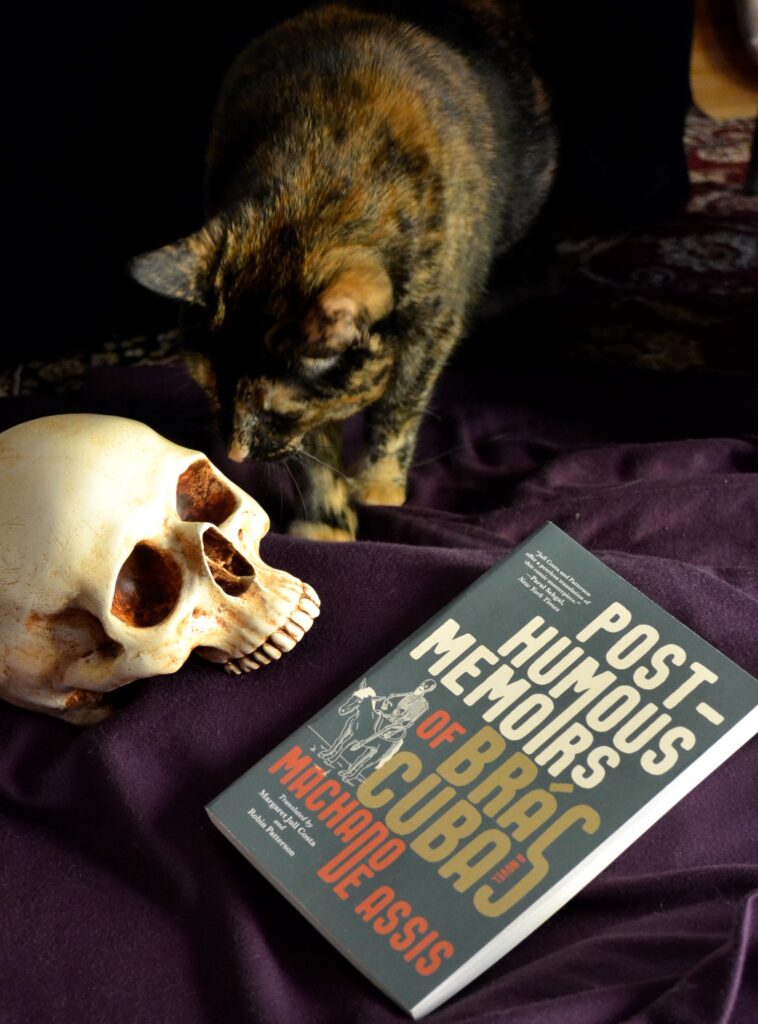

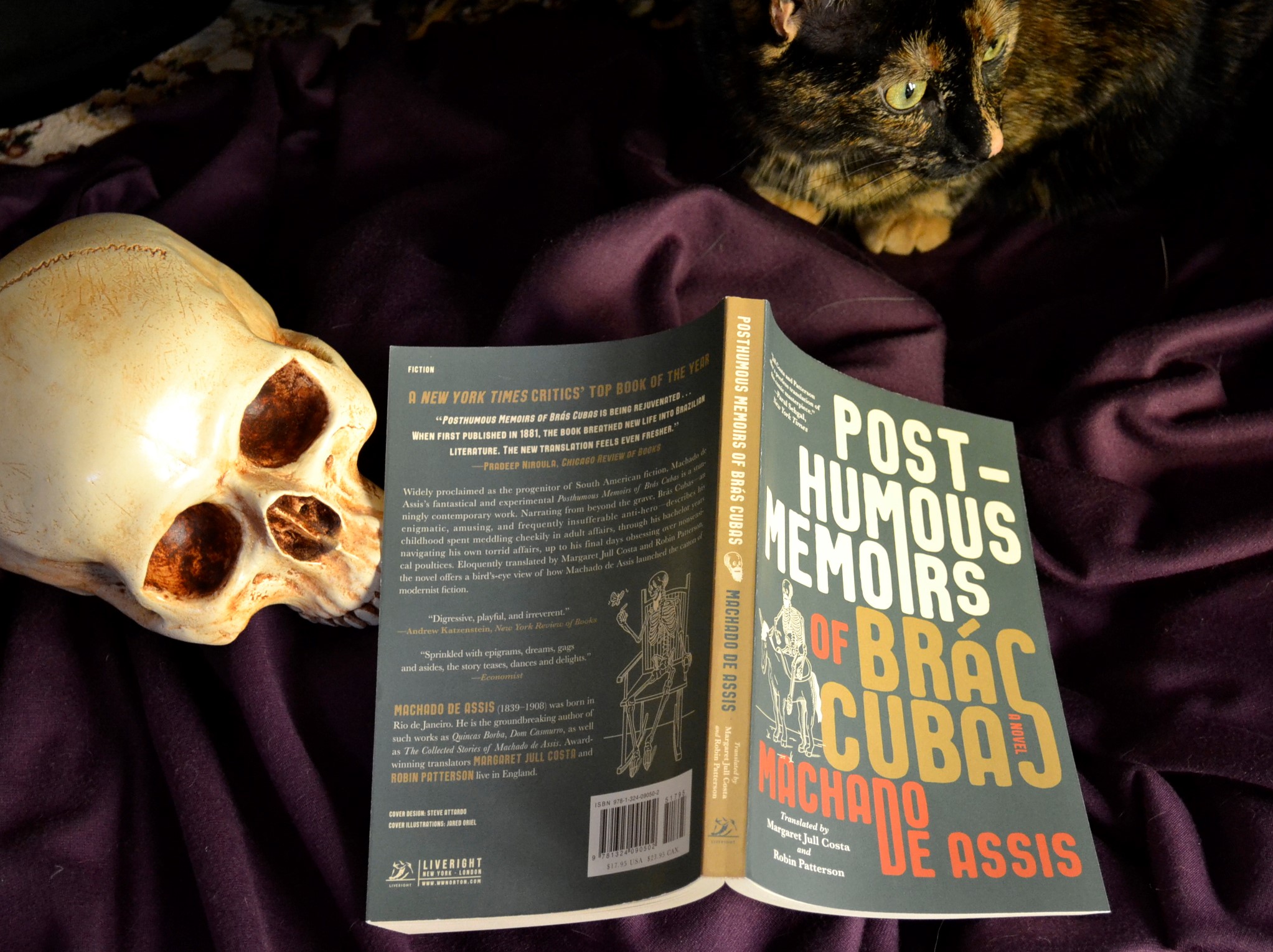

A Homage to Sterne

What I like most about this book is the homage it pays to one of my favourite books, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. Short chapters, leaps to different subjects, a story that goes at breakneck pace and rambles at intervals — all of that good stuff. The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas (Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas) is an entertaining read that can be devoured quickly and easily in two or three sittings.

And, of course, it has the spooky premise of a man writing his memoirs after he has died in a tone that is jovial, but at the same time sharp and insightful. I will say that I wish there was a bit more content related to Cubas’ death and later life, but overall this book doesn’t make a claim that it fails to deliver on.

What Stands Out

For something published in 1881, this novel is incredibly accessible and readable for a modern audience. The technique and structure are far ahead of their time, while still emulating material and ideas from the past. The conversational tone draws the reader in as the chapters fly through your fingers. One minute you’re reading an extended metaphor about moths, and the next you’re musing about the function of legs along with the narrator before being pleasantly plopped back into the story.

It really shouldn’t all work together, but in some very magical way it most definitely does. No amount of words can really describe how it does either — and that’s what happens when a writer is a master of style, technique, and keeping the reader engaged with the prose.

What Stands Out in Less Beneficial Way

As much as I enjoyed all of the random asides and twists of narrative, it couldn’t hide the heavy presence of sexism, racism, the slave trade, and various other horrible things. All of it was bad, but the sexism was especially lurking at almost every corner of the plot and expounded upon at length by the main character. Female characters are mostly the same and none serve any real function other than to flatter the protagonist or be an object. This isn’t something unexpected in a novel published at that moment in time, but I found the writing style particularly accented it in this case.

When you read his biography, you quickly learn that Machado de Assis was actually an abolitionist descended from freed slaves. He was of African descent. He was taught with and by women and treated his wife extremely well. But, unfortunately, he also kept all of his personal politics out of his writing and chose instead to write books that more aligned with the public opinion at the time. It’s quite disappointing.

The other problem I had with the novel was its lack of any real point. Part of that is completely intentional. The reader is supposed to view Cubas as a man who has wasted his life, but I found that unlike Sterne, Machado de Assis doesn’t quite manage to make this into something the reader can feel. Unsatisfactory endings can be extraordinary, but they have to be carefully crafted to be so. In the case of this novel, I didn’t get the ‘pointlessness as point’ feeling enough when reading the prose. Instead, I was just left wondering if I missed something or if the whole purpose of the narrative was to examine the protagonist’s affair with a married woman.

There is a philosophical component to the book as well, but I personally didn’t feel like it was integrated well enough to serve the purpose it was intended to in the plot or the authorial statement.

Cleaning The Windows Part II

The cats are plastered to the sitting room windows for large portions of the day, and it’s great to see them enjoy the outdoors from the safety of the indoors. However, this is the time in the year when I notice that all of those chirps and snorts and snuffles have left a lot of dried cat spit on the glass. We’ve already done the hard part of cleaning the outside of the windows, but clearly I cannot neglect the inside.

I had no idea five cats could leave so much spit, but the bottom of the panes are nearly opaque in places.

Ew.