Don’t Try This at Home

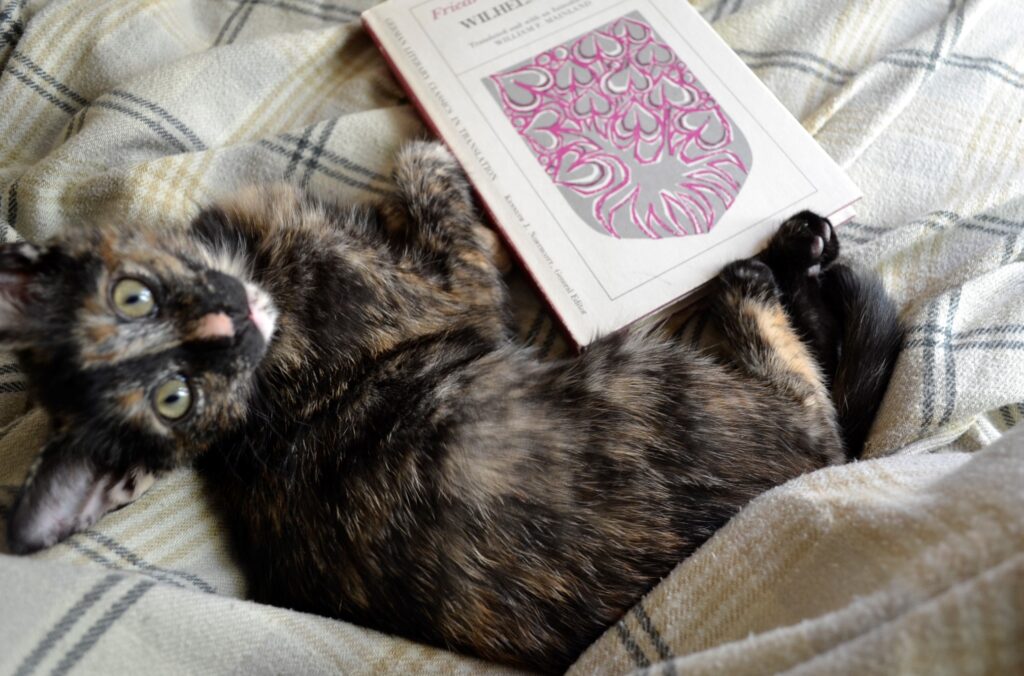

The first time I remember seeing an incidence of the ’William Tell’ archery game, was when I was far too young to know what it was. I was just a kid, watching The Swan Princess and seeing the prince shooting an arrow into an apple balanced on the head of his trembling lackey. It was many more years, and many more exposures to arrows splitting apples in half while leaving skulls intact, before I actually looked up Wilhelm (William) Tell. And it was only just recently that I was able to obtain a copy of Schiller’s play Wilhelm Tell.

In my research, I’ve also discovered the shockingly numerous criminal cases involving rounds of ‘William Tell’ gone wrong. It’s not a game to be played at all. Ever. Even when one is an expert marksman and completely sober. But I marvel at how many individuals decide to drink and then play it.

Just, please, don’t try to play this game at home.

A Hat on a Stick

Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell is a five-act play that tells the story of Wilhelm Tell, a hunter and marksman, who played a role in the Swiss fight for independence from the Habsburg Empire. Gessler, the governor, forces Wilhelm Tell to shoot an apple off of the head of his son as a cruel punishment for not showing due reverence to a hat that the governor has placed on a stick to test the loyalty of the people.

Tell manages to split the apple and not his son’s head, but admits that if he had failed he would have killed Gessler. Gessler therefore tries to imprison him and this leads to a general uprising of the Swiss Cantons and their fight for independence.

The play is a brisk-paced story of revolution and patriotism. It details the way a conflict doesn’t just involve those at the top of the political ladder but also those who have nothing to do with politics and are just living their normal daily lives and trying their best to stay out of the fray. Tell doesn’t directly join the cause but offers his help when needed and then becomes involved when Gessler’s cruelty nearly kills Tell’s own child.

Revolution

This play is not just about politics. It tells the story of a personal revolution in the character of Wilhelm Tell himself. He is a hunter that doesn’t want to get involved in the political strife around him, but that strife comes to him and he realizes that he is compelled to act. Tell kills Gessler for a mixture of both personal and political reasons, melded together into an inseparable force.

Something similar happens to the character of Rudenz, who at first is one of Gessler’s party, but rapidly changes allegiances when his intended, Berta, makes it clear that he won’t win her heart by supporting Gessler’s cruelty. Again, there is the presence of both personal and political reasons for his change of heart — and the reader is left wondering which is the primary motivation for his actions. Which reason is more powerful? Which should be?

Schiller makes the audience consider the idea of revolution is more ways that just the obvious one. He shows the facets of it proceeding in an individual psychology, as well as binding together and uniting a group of individuals. That alone makes the play worth the read — for it takes a lot of skill to accomplish that in the course of a 140-page play.

A Sense of Non-Ending

One criticism I would offer for Wilhelm Tell is that I found the ending a bit abrupt. Tell helps the murderer of the emperor flee after denouncing his crime, which said assassin has compared to Tell’s killing of Gessler. Schiller leaves enough space for the audience to consider if the murders are indeed similar — since both involve an aspect of revenge. However, Tell’s killing of Gessler had a cause behind it that the emperor’s murder lacks since it was primarily for the profit of the murderer.

I do appreciate the question that Schiller is encouraging the audience to consider, but at the same time I felt that the ending didn’t give the sense of finality that I expect at the end of a play. The letting go of the emperor’s murderer overshadows the final few lines of the play that do include what should feel like finality — Berta and Rudenz’s marriage and Rudenz’s freeing of his bondmen.

However, these events seem rushed and don’t provide a feeling of ending after the conclusion of the ‘William Tell’ portion of the narrative.

Too Short? Too Long?

Wilhelm Tell needs at least five acts to accomplish what it does and I don’t think there is a way to make the play shorter. Neither do I think there is a way to make the play longer — though, perhaps the last act could use a bit of an expansion.

Apple Picking is a Much Safer Activity

Why shoot arrows into apples balanced on the heads of your friends and relations when you could just go and pick said apples off of a tree instead? Add some hot chocolate or a trip to a nearby antique market and it sounds like a perfect afternoon during which no one is accidentally killed.

Every year, my lovely spouse and I go apple picking at one of the local orchards. Last year we had a basement disaster that meant we missed out on our yearly ritual, so I’m extra excited for it this year. Now we’re just waiting for the perfect day to dawn crisp and cool and for the leaves to have just the right amount of fall colour in them before we set off to get our winter’s supply of apple goodness.

And not a single one of them will be used for any form of target practice.