Where You Least Expect to Find it

I’ve never really been one for poetry when it comes down to it. Occasionally there are exceptions to this rule. I enjoy Pushkin and Tennyson, but it’s rare that verses move me the way that novels do. However, when I do read a line that I like, it sticks with me.

My spouse and I were watching Jojo Rabbit, which ends with Rainer Maria Rilke’s words,

Let everything happen to you; beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

I can admit that the words made me cry. A lot. I live with an anxiety disorder and I’ve been through two health scares in the last two years. As a result, I deal with a lot of fear on a constant basis. It’s a battle to live in the moment without being terrified of what disaster might or might not happen in the future. Rilke’s words reminded me to keep going and keep living despite the worry and the fear that dog my steps most days.

Just keep going. No feeling is final. Not even fear.

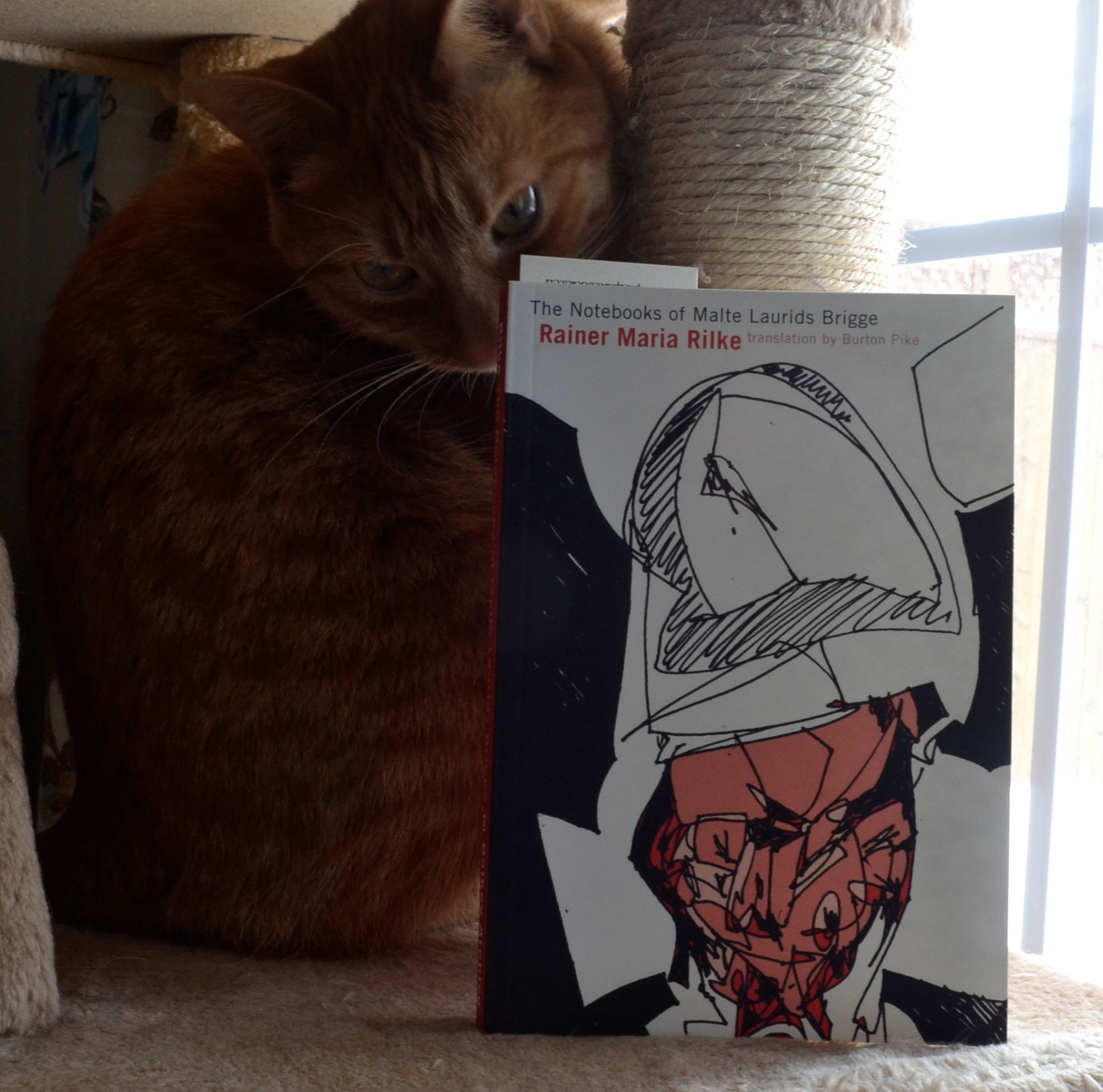

Looking in my stacks, I saw that I’d bought Rilke’s novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, and I decided that now was the perfect time to read it.

The Perils of Modernism

Literary modernism began in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and it was a movement in literature that sought to stretch the forms of both poetry and prose works to the utmost. The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge is an early modernist novel and, as such, one should be aware of its lack of traditional structure before one embarks on the task of reading it.

The novel concerns the observations of a young poet, Malte Laurids Brigge, who is teaching himself to see the world around him and write about it. He is also trying to interpret his childhood through adult eyes and is struggling with who he is and his place in society.

These are the themes that bind the novel into a cohesive work, though the structure of the book does not include a plot or a driving action per se. Instead, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge reads like notebooks — full of the beginnings of stories, diary entries, and memories. The reader is exploring Brigge’s brain as he is trying to make sense of what he sees, what he writes, and what he remembers, as well as old fears that begin in childhood and come to call later on in life.

A Different Kind of Reading

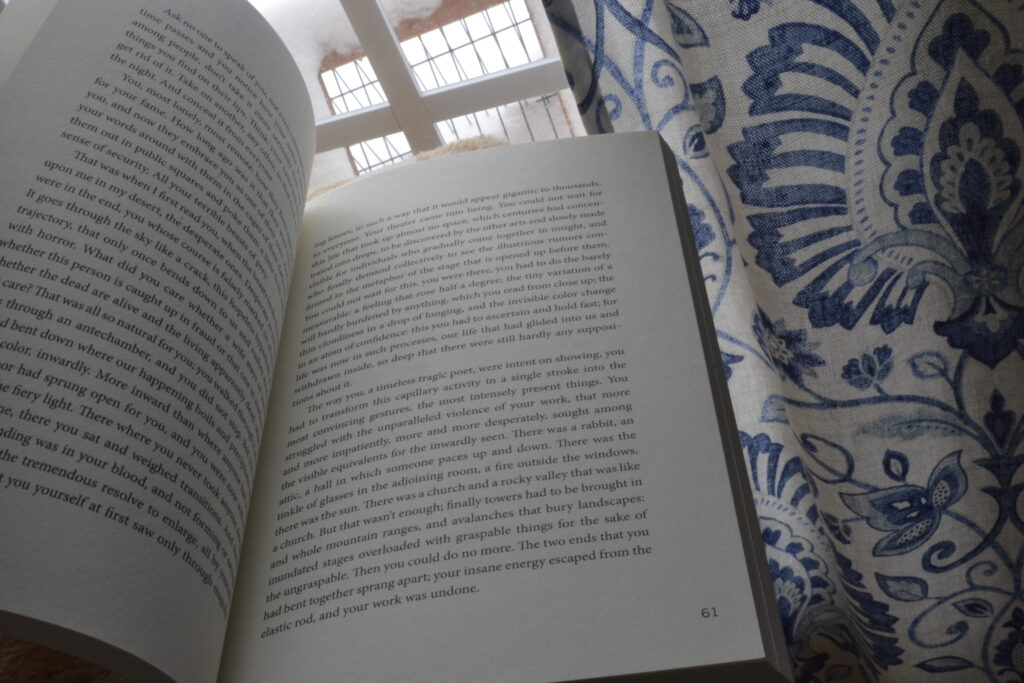

Reading Rilke — and most modernists — involves a bit more of a time investment than traditional novels. Not so much because the writing or content is more challenging, but more because of the richness of the technique involved. Rilke’s writing is very lyrical and uses language, turns of phrase, imagery, and metaphor to their maximal effect and it takes careful attention from the reader to appreciate fully what he is saying and how he is choosing to say it.

Particularly, I was drawn to his passages describing the feeling of mortality as a death that we carry inside us that eventually manifests and finds expression when the time of death arrives. The death of Brigge’s grandfather is thusly a ‘loud’ death full of pain, screaming, rages, and demands that swallows who the man was and takes over the last of his life.

A brief example:

Cristoph Detlev’s death had now been living for many, many days at Ulsgaard, and spoke with everyone and demanded. Demanded to be carried around, demanded the blue room, demanded the small salon, demanded the large hall. Demanded the dogs, demanded that people laugh, speak, play, and be silent, and all at the same time. Demanded to see friends, women, and those who had died, and demanded himself to die: demanded. Demanded and screamed.

Ghost Stories in Miniature

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge includes several ghost stories that are compelling in both their adherence and departure from the typical. Brigge’s maternal grandfather’s home features a ghost named Christine Brahe who has a tragic story that is never detailed. Her appearance is sudden and unexpected and so is the fading of the narrative — in that half-finished way in which many stories in childhood don’t have real endings. Brigge never figures out who she is, but the apparition remains a part of his experiences even in this incompleteness. Several figures from Brigge’s childhood have this same sense of incompleteness. Names mentioned but never expanded upon.

Christine Brahe isn’t the only ghostly experience. There are ghostly hands and presences, all ethereal and faded at the edges of Brigge’s recounting of them. It is about their existence, not about explaining them that he focusses on.

Diary of a Young Poet

The novel also includes several passages concerning Brigge’s life as a struggling young poet in Paris who is trying to write what he sees all around him. Detailing trips to the hospital, fevers, and neighbours, Rilke brings an artful complex layering of description to items of everyday life.

For example, he describes the experience of living above, below, and beside other people. Making note and getting used to their habits and noises. He turns this common experience into two different things and two different stories.

One story is a tale of a man in a fight against time. He hears the phrase ‘time is money’ and therefore counts time and tries to save it, thinking of it as a quantity but one that is constantly disappearing in spite of his best efforts. Eventually he lays down in bed and doesn’t move for fear of losing more time and therefore more wealth.

The other story is another ghostly narrative of the ever-present sound of a falling tin lid in a vacant apartment that Brigge imagines is still occupied.

I was fascinated by Rilke’s simple talent of taking something ordinary and stretching it into new perspectives, something that is further emphasized by the novel’s modernist style.

Beauty and Terror

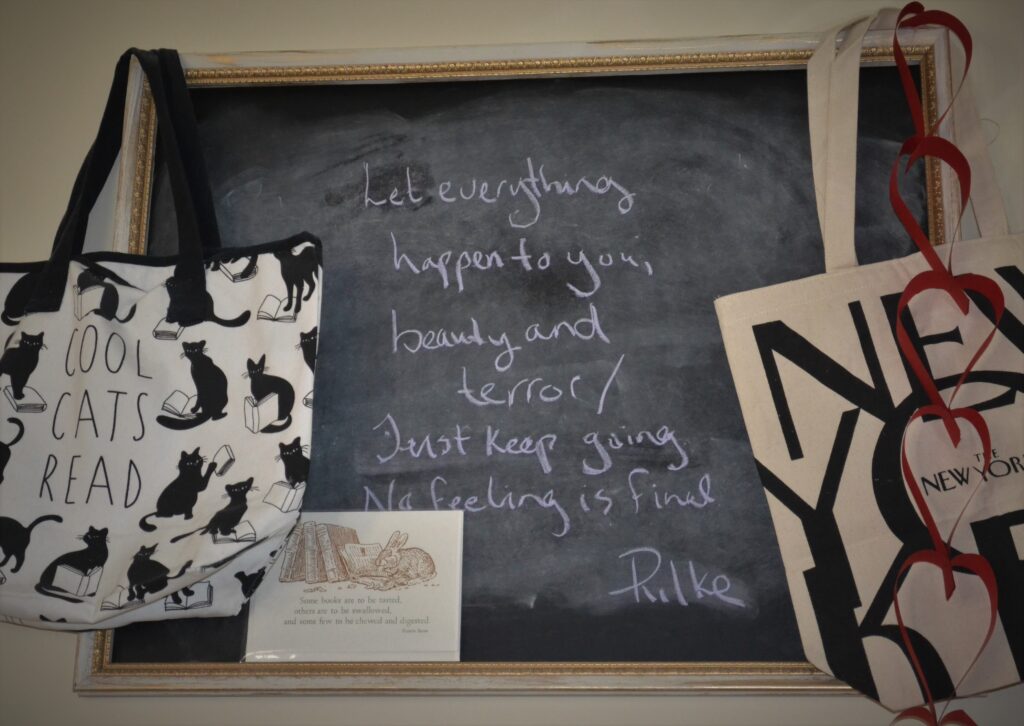

There’s a chalkboard in our living room that I used to use for deadlines when I was submitting stories to literary magazines. It’s seen little use in the last few months after hectic basement disaster renovations, and the health-related stressors because it can be hard to write short stories in the midst of chaos.

So I erased the year-old deadlines and instead I wrote Rilke’s words in purple chalk. I read them at least a few times a day, when I feel the terror of being lost or afraid or hopeless. I also read them when I watch the beauty of birds at the birdfeeder or see my spouse smile.

I feel the beauty and the terror. And I keep going.

I live and try to appreciate every second.