The Writing Process

The thing about writing is that it’s something that no one can precisely instruct you in. One can give very good advice and one can listen to very good advice, but there’s no set way to proceed as a writer. How you work and your process are unique to you. One of my favourite examples of this is when you look up the work spaces of notable writers.

You’ll see a crowded desk in a corner overloaded with papers, a sofa, a shed, an armchair with a green board across it. I personally write with the help of a bamboo lap desk, curled up on the sofa beside the chattering television. I also tend to sit cross-legged in front of the coffee table that my grandmother gifted to me when I first left home — it’s composed of pressboard and some kind of 1970s ode to mid-century modern.

If I was asked to give advice on how to about writing, the only thing I could suggest would be pretty obvious. I’d say that in order to write, you need to read. But, of course, usually if you’ve decided to write you’ve done plenty of reading already and doing more of it is just icing on the well-written cake.

How This Book Came to Be

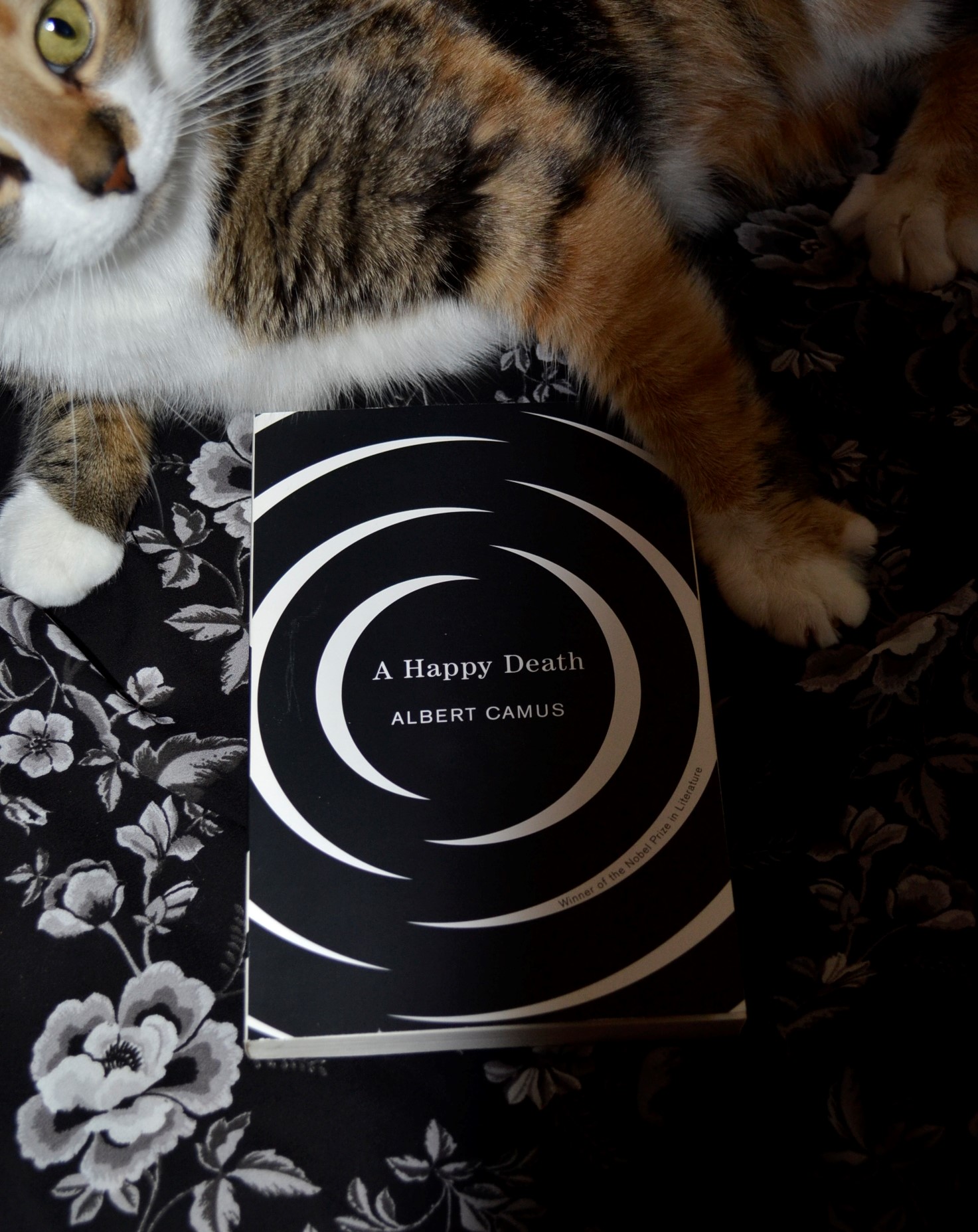

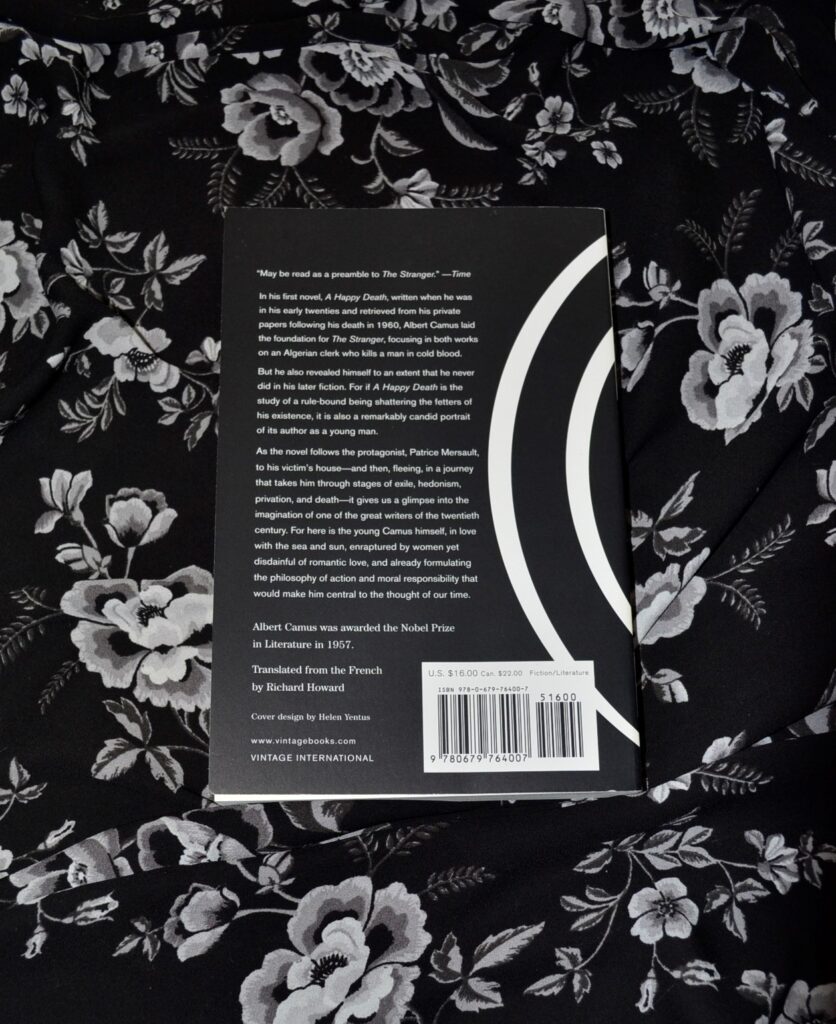

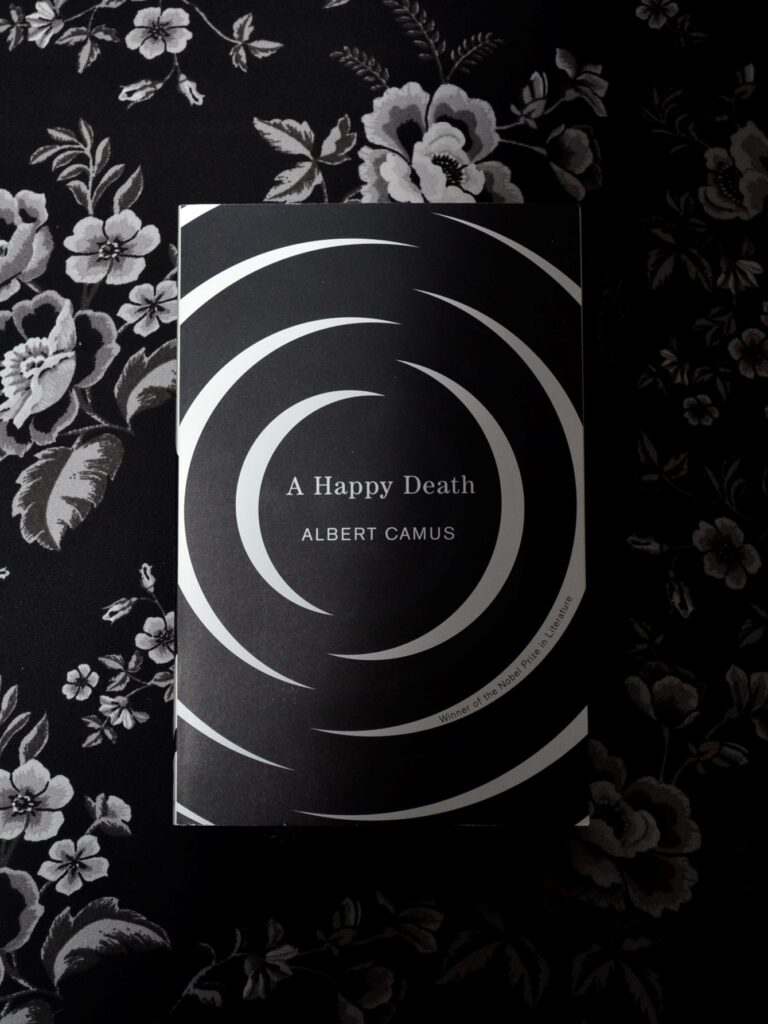

Albert Camus’ A Happy Death (La Mort Heureuse) has a bit of an atypical trajectory from creation to publication. Namely, it was published over eleven years after Camus’ death. It was actually written by Camus in the late 1930s when he was in is twenties, making it arguably his first novel — though it was set aside and found among his personal papers upon his death.

This aspect of the book’s history is important to keep in mind when reading and discussing A Happy Death. Though the novel is complete in terms of narrative, it’s not exactly finished per se. There’s a note in front of my edition that explains that the decision was made to publish the work because reading as much of Camus’ as possible helps readers and scholars understand who Camus was as a writer and his process.

I would generally agree with this statement, as long as the reader is dedicated enough to know and understand the history behind the unpublished work — including why it wasn’t published and its place in the author’s body of work. Vintage press makes that easy with this edition of the novel, which excludes an extensive afterword with analysis as well as a section of notes and variants of the text including corrections made by Camus himself on the manuscript.

A Happy Death

A Happy Death is essentially the story of one man seeking to have a happy death. Patrice Mersault kills a man, takes his money, and then proceeds to try to find happiness. Camus’ style is stark, but compelling. The narrative moves at a brisk pace and there is a sense of not a word being out of place.

The novel is existential, which means that the reader is expected to invest a good deal of time thinking about concept, theme, and idea — but that doesn’t mean that the author can neglect the framework of words, phrases, and flow. Words, phrases, and flow are what the concepts, themes, and ideas are conveyed with and hinge upon, after all. Camus masterfully constructs a framework that the higher concept of his work not only hinges on, but uses as a catapult — striking the reader forcefully, but in a way that compels you to keep reading and keep thinking about what makes for a happy death as opposed to a violent one, or a natural death as opposed to a conscious one.

That’s a pretty impressive accomplishment for a manuscript that is clearly still in need of a final polish.

A Comparison to The Stranger

A discussion of A Happy Death would not be complete without a discussion of its relationship to The Stranger (L’Étranger). Both novels have protagonists that have similar names and several characters between the books have either the same name or similar names. Both novels include a murder and both have a main character who is isolated by an utter lack of empathy and apathy.

In some ways A Happy Death is an early draft of the later book, but in most ways it’s a completely different novel. The Stranger takes some of the ideas present in A Happy Death and builds on them, stretches them further, or else takes them in different directions.

A Happy Death shows a bit of a roughness in Camus’ usually perfectly precise planning and structure, as well as in a few passages, but in general, it’s barely distinguishable as an early draft. Only the missing polishes that finish a final draft of a manuscript are lacking.

My First Drafts

When I read this book, I wondered if I would want my first drafts and abandoned projects published posthumously. Thinking of some of them makes me cringe, but others I wouldn’t mind as much. However, I can say that I would be confident that upon reading even the dredges of my writing, a reader could definitely mark an evolution over time.

That’s what writing is — an evolution. It takes time, it takes effort, and it’s a journey that stretches out over months, and years, and decades. It’s a craft that you are constantly working at, striving not for perfection but for the ability to convey the art that you have in your head onto the paper with ink and words and the skill you’ve worked so diligently to acquire through reading, writing, and honing a style that is uniquely yours.

It takes patience. It takes time. And, most importantly, it takes the determination of knowing that you will always be demanding more and more of yourself and your words no matter where you are on the road to your magnum opus.