Last of the July Noir

I can’t believe July has flown by already, and the clerk at the local feed store where we get birdseed agrees with me. Maybe it’s been the heat, or maybe it’s been our packed schedule, but it feels like fall is just around the corner and where did the theatre season go? Though, so far, our season has been a bit sporadic because for some reason I decided to pack August with four different plays. Why? I don’t know. I’m sure that I had a reason but it is utterly lost to the sands of time.

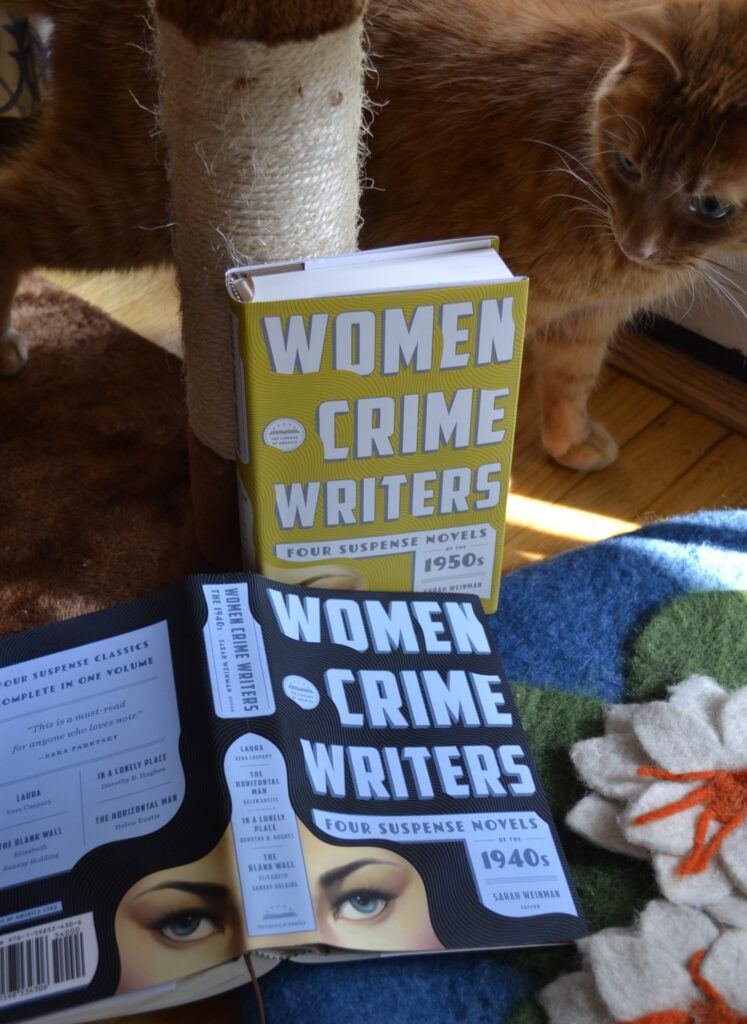

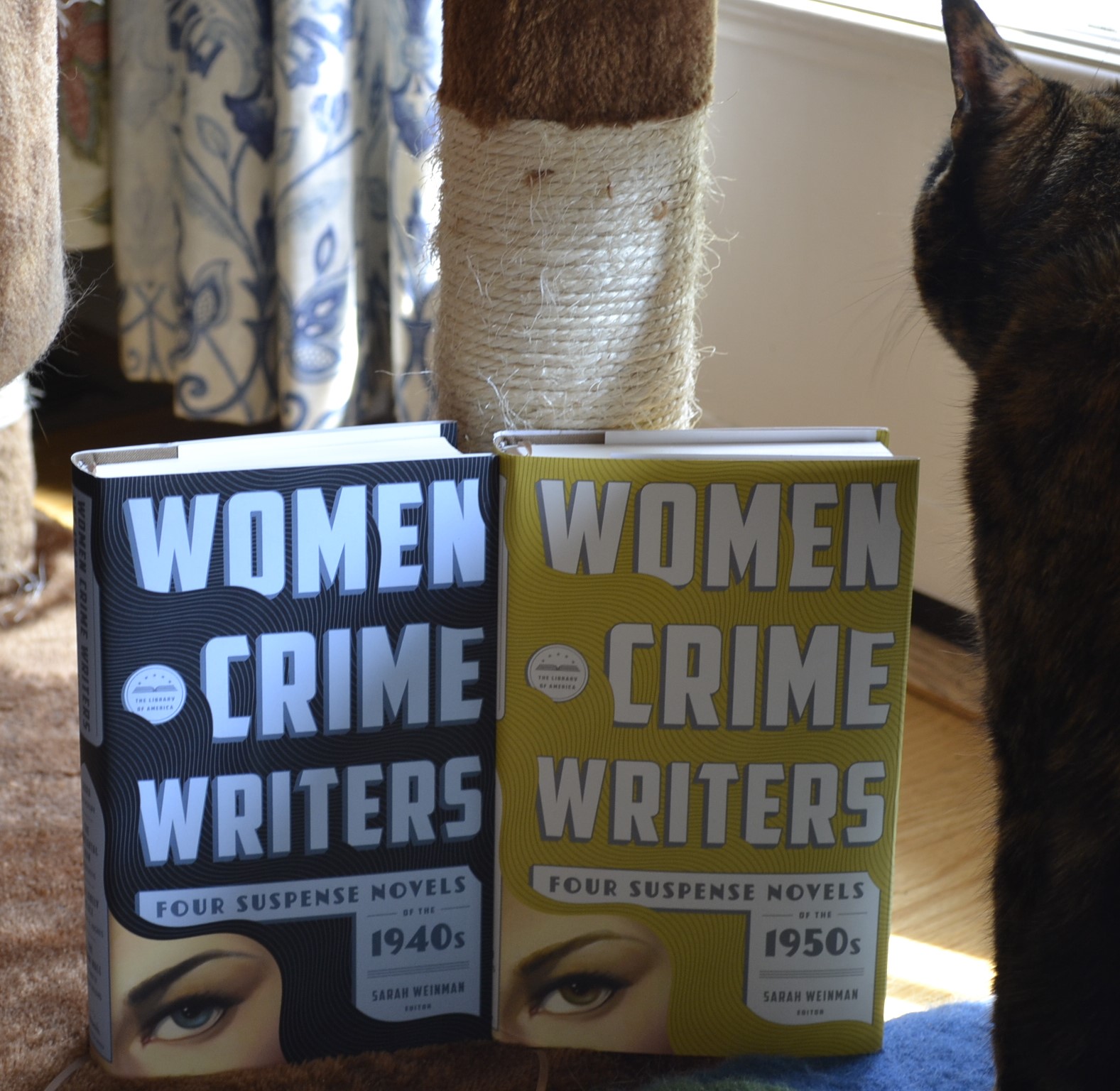

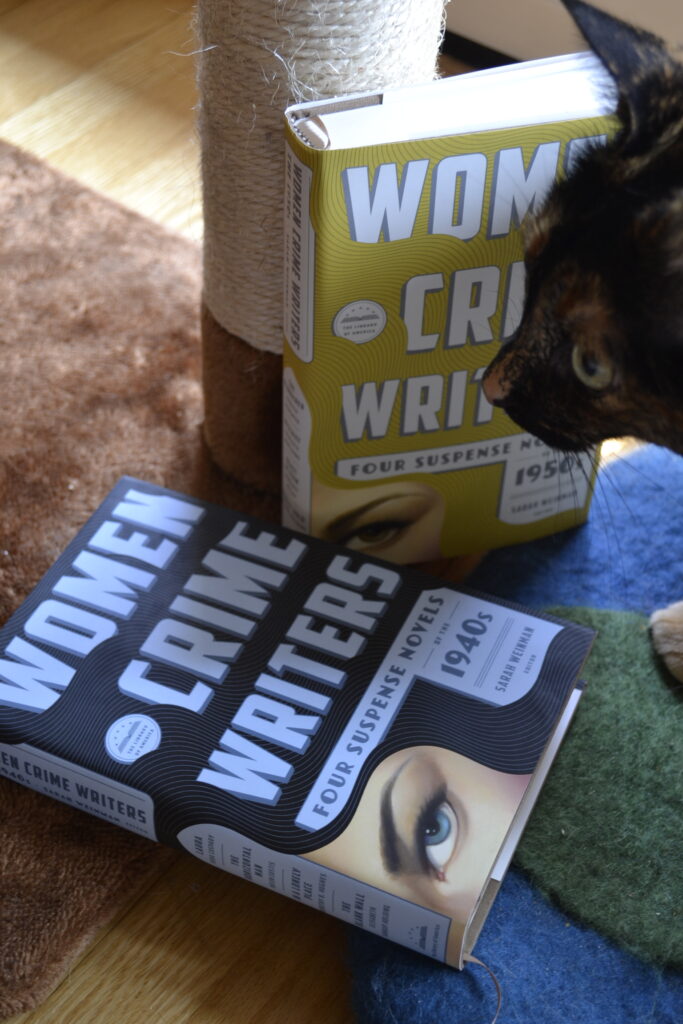

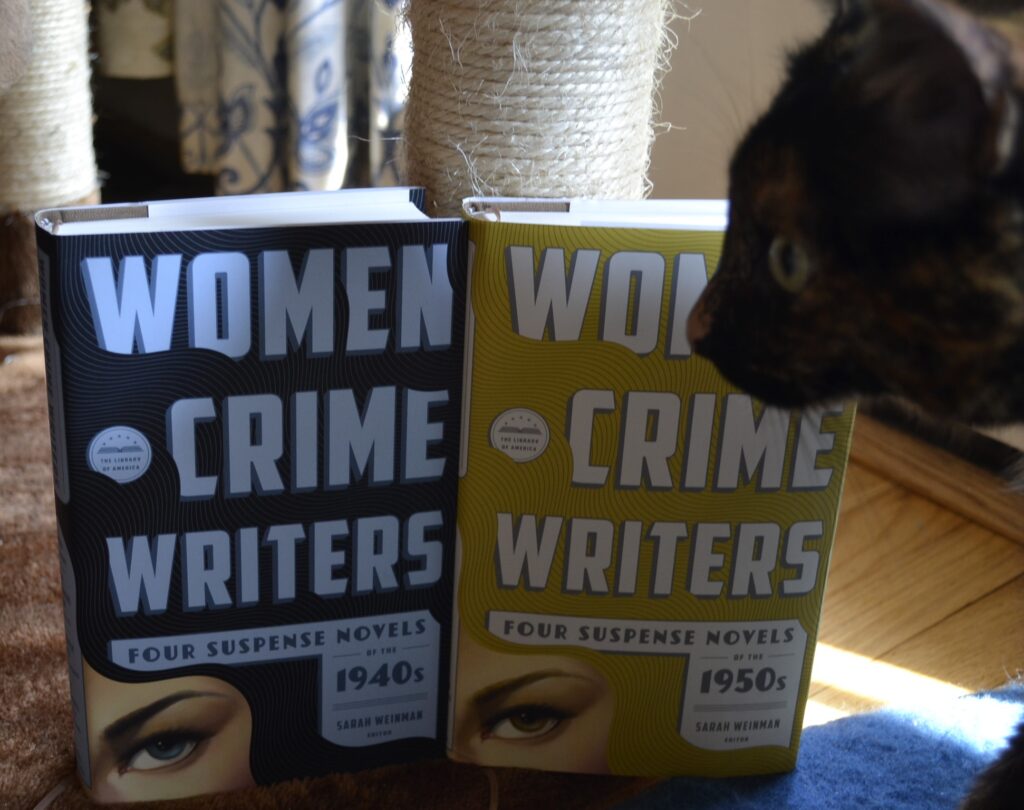

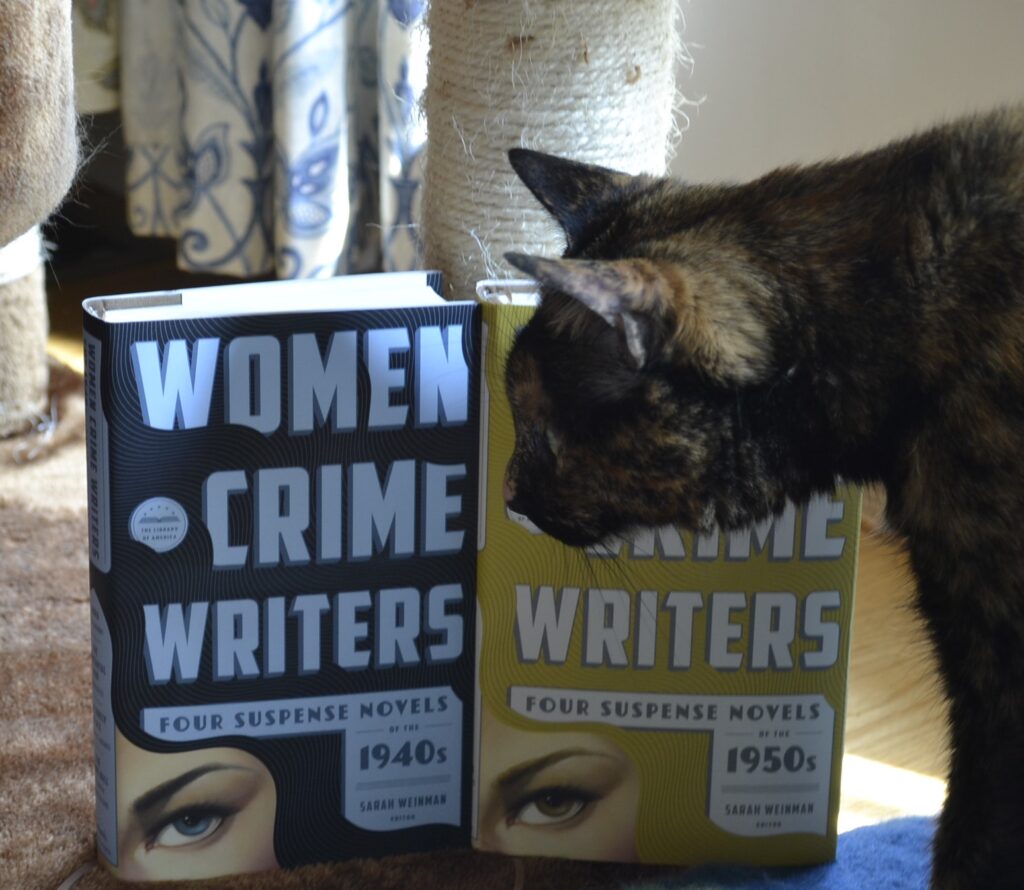

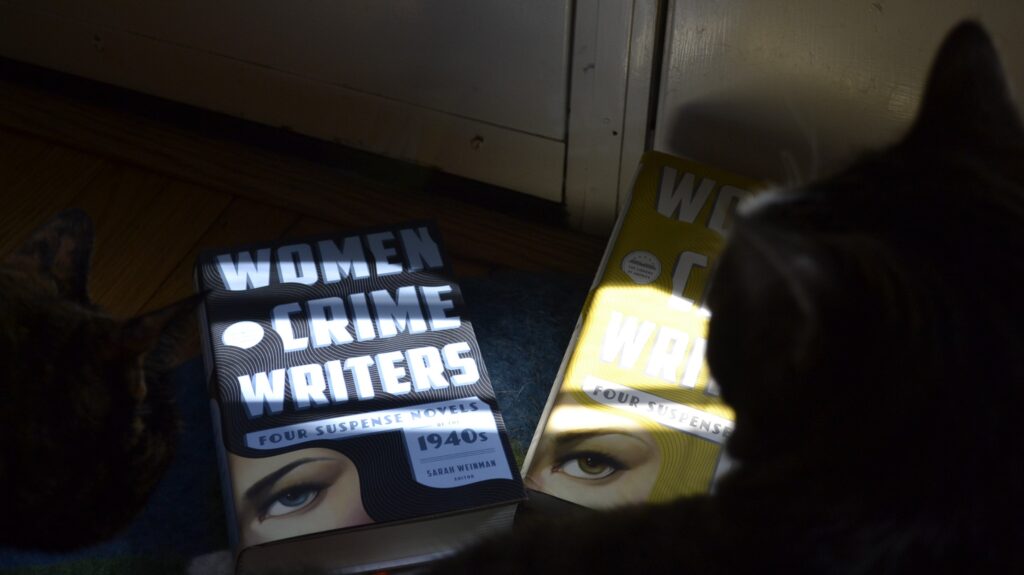

As July ends, so does my noir feature. I really learned a lot reading through the Library of America collections, and linking my reading to the films that I love. Its inspired me to maybe branch out a bit more into film in the future, but that’s another story. I cannot emphasize enough that these collections are a great starting point, but I hope that if you enjoyed them, you’ll be inspired to delve deeper and look farther for more noir. I also hope that preserving these classics will mean more preservation efforts in the future.

Also? I’m kind of hoping for a 1970s noir or neo-noir Library of America volume at some point in the future.

Some Context: Part One

Female writers have always had more of a challenge getting published in literature, but when it comes to genre the uphill battle can be even steeper. This is especially true in genres that were thought to be ‘for men’ and were thusly aimed at men. However, there were women who pioneered what noir could be and were instrumental in creating narratives that had more grit and depth than was previously thought possible.

In the 1940s, female writers were still largely trapped by pressure to be a housewife or to write about family or the domestic sphere. But even the whitest of picket fences can hide a twisting darkness. And that very pressure could itself serve as one of the most complex themes of noir — that of dreams deferred and decisions made with extreme regret.

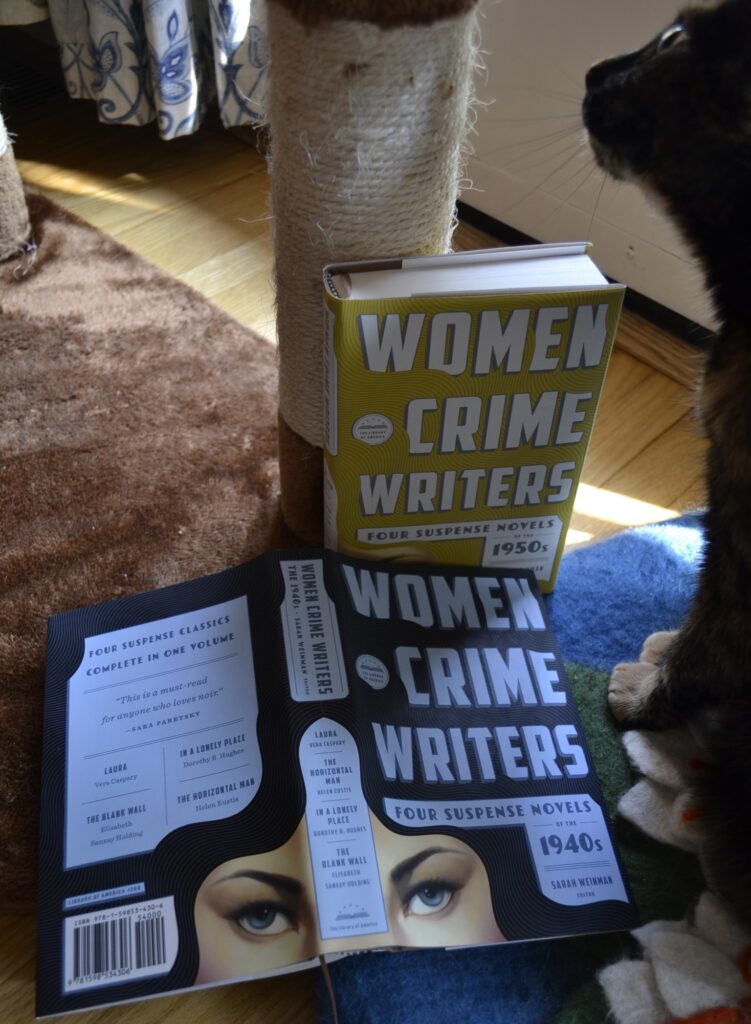

The 1940s

Laura

Laura by Vera Caspary was published in 1943, and it is probably more well-known as the book that inspired the film made by Otto Preminger in 1944 starring Gene Tierney, Dana Andrews, and Clifton Webb (and my favourite actor, Vincent Price). It’s a novel that begins with a murder, but turns topsy-turvy when the assumed victim shows up alive. What Caspary is really doing is presenting the reader with the pressure felt by women to get married and have a family even when they are happy being single and enjoying successful careers. She delves into the harsh reality that women of the time had to be better workers and more successful people in order to be seen as worthwhile in an office setting. Very biting and very worth the read.

The Horizontal Man

Helen Eustis’ The Horizontal Man from 1946 delves into the world of a women’s college. It’s a murder-mystery but also a critique of academia and its insular environment. It’s a harder read because it includes some very outdated treatment of mental illness and a very cringingly cheesy romance narrative, but it does have some moments of jaw-dropping twists.

In a Lonely Place

In a Lonely Place was written by Dorothy B. Hughes and published in 1947, and it is the most famous novel in the volume. Made into a film by Nicholas Ray (who also directed Rebel Without a Cause) in 1950 which starred Humphrey Bogart, it’s a title that is sure to ring a bell. But the book and the film are two very different entities. In the book, Hughes takes us inside the head of serial killer and rapist who hates women. He is often rejected or feels that they are out to get him and has paranoid delusions about women as some kind of force that is out for his ultimate destruction. In the film, the same character is innocent. Women fall all over themselves over him. Wow, what a different and worse story. While the film has its merits, it simply cannot compare with Hughes’ novel and I would strongly recommend reading the book before even going near the film.

The Blank Wall

Lastly, Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall from 1947, might seem like a simple domestic thriller on the surface, but it rapidly becomes a wild ride through the prejudices of wartime America and a demonstration of how far an individual may go to defend their own. Sanxay Holding also throws in a critique of the lost of identity that often occurred to women of the time period when they married and had children. Their past, their preferences, their personalities, and their individuality was consumed by being someone’s wife, someone’s mother, and someone’s daughter-in-law.

Some Context: Part Two

As the 1940s subsided into the 1950s, women began to experience broader roles in society and broader roles in noir — even if the restrictions and/or pressures of domestic life were still very much present and very much a part of the story. Finally, women were not restricted to being the victims of the story or having roles in the narrative that were heavily defined by men or commitments to family. Now, there were noir novels where the woman could be the perpetrator and where female characters could express rage, grief, and other extreme emotions.

The 1950s

Mischief

Charlotte Armstrong’s Mischief was published in 1950 and features a female perpetrator. The evening in question starts innocently enough, with the babysitter arriving at a hotel room to take care of a little girl while her parents go to a party. But what follows is a descent into chaos with an unhinged killer whose motives are as cloudy and unpredictable. This novel was also made into a 1951 film called Don’t Bother to Knock directed by Roy Ward Baker and starring Marilyn Monroe and Richard Widmark. It’s not a bad film, and it features a rare unglamorous role for Monroe — although the screenplay differs quite a bit from the novel in order to made the role more flattering and less violent.

The Blunderer

The Blunderer was written by Patricia Highsmith and published in 1954. There were a lot of Highsmith novels in these collections, and it was a bit disappointing. The Blunderer wasn’t Highsmith’s best. It’s a very complex story about a man who commits a murder and a man that doesn’t. Two wives are dead and either both men will be declared innocent or both will pay the price. I found the description of the wives inherently misogynist, and that Highsmith continually defended the actions of two men that were both bad, albeit in different ways. There were several logical errors and, in general, the book went on too long.

Beast in View

Margaret Millar’s Beast in View was published in 1955, and it is a book that feels very ahead of its time. At the centre of the narrative is a woman who has left a dysfunctional family behind, but now finds herself the recipient of some disturbing phone calls. Events unfold quickly and lead to some strange places including a brothel and a disreputable photographer. There’s also a female perpetrator in this one, and a complexity of character that is very compelling. As a heads-up, there is some very outdated attitudes concerning mental illness, as well as the homophobia that was all too common in the 1950s.

Fools’ Gold

Fools’ Gold was written by Dolores Hitchens and published in 1958. It follows two young boys — who have already had trouble with the law — through a robbery that shortly goes completely off the rails. The writing in technically good, but I found the plot less compelling than it could have been. Hitchens intends the reader to go on a character study of the two main characters and contrast them. But what ends up happening is a frustrating look at a perpetrator who refuses to grow up and to acknowledge that there are people on the planet that are not him. Inadvertently, Hitchens has achieved a relevance to the current age where literature is discussing male privilege, and a lack of accountability, empathy, and impetus to mature in members of that population, and how society can sometimes encourage this.

Augh-tober!

Now it’s time for August which means TCM’s Summer Under the Stars feature — a mainstay in our household. Plus, it means that spooky time begins both on the blog and in the house. The décor is coming out, more décor is being added, and the books have been piled. I’ll be reviewing spooky selections all month long, and maybe talking about a few films along the way. Stay tuned!