Growing Up is Hard

Sometimes when the New Year is young, it’s easy to look back on other times of transition. I know a lot of fiction describes a moment where suddenly one transitions from childhood to adulthood, but I think the reality is that childhood ends in a series of moments, realizations, and formative events. Things suddenly look different. You think about them differently or you have a different role than you used to have before.

One of the things I specifically think back to is my time at my grandparents’ cottage. When I was a kid, all I could think about was the lake and the endless summers swimming in the cold water that I couldn’t get enough of. Family sat on the shore and talked while dinner was cooked inside, every weekend a pot luck of salads and familiar dishes that were always brought and we always ate with relish. Bonfires, talking, card games, even lawn darts. It was so magical for so long.

Then, slowly, it changed. Slowly, I stopped going out to the cottage. I had to work or I had homework. I wasn’t comfortable enough in my own skin to wear a bathing suit. Something changed. I was no longer the little girl that nearly breathed lake water for three months of the year.

Now, my family will soon be parting with the cottage. I haven’t even seen it since the year or so after my grandfather’s death. I know it’s the same place, but it’s not the same now. I can’t go there without seeing his ghost and all of the time that’s gone by. Without thinking about how much I miss him and how much I miss what the lake used to mean to me.

I hope whoever buys the property will enjoy it as much as I once did. Because even if the magic is lost to me forever, I know that other children can find it and that the lake will welcome them just like it did me.

A Dysfunctional Family

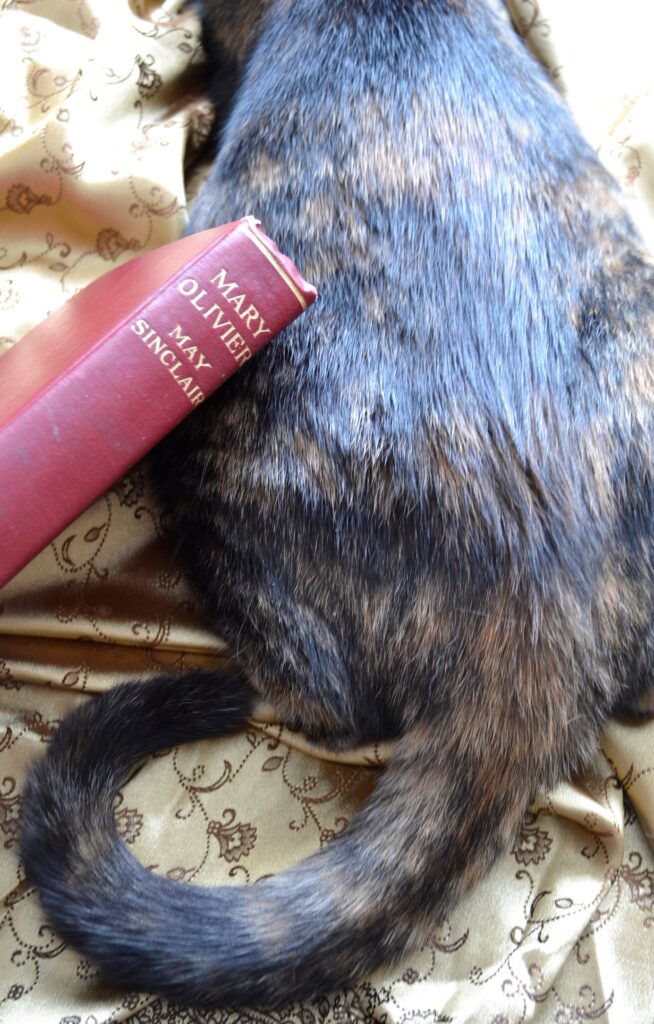

May Sinclair’s Mary Olivier is a novel about a family growing in the Victorian era and specifically follows the life of Mary Olivier as she tries to find her own identity and deals with the increasing strife in her family. Mary is the youngest of four children and doesn’t quite fit in no matter how hard she tries to. Fiercely intelligent, she seeks knowledge and truth and to find both of those things for herself instead of listening to the ideas or fulfilling the expectations of those around her.

Mary struggles to find a connection to her family but is often left disappointed if not outright rejected as she attempts to be a good daughter and sister, without losing what’s most important to her: herself. Sinclair has written a compelling book about a very dysfunctional family with complicated relationships that existed in a very restrictive world that didn’t favour the open discussion of thoughts, feelings, or anything considered ‘dark’ or ‘difficult’.

Sinclair writes about subjects that would have been very different and bold for 1919, including the idea that women had much to contribute to scholarly study and the intellectual world. For that alone, this book is worth the read.

Mother and Daughter

Mary is constantly confronted with a painful truth that eventually destroys her life and the lives of her siblings. Mary’s mother has a favourite in the oldest son, Mark, and doesn’t have any affection for any of the other three children. Mary, Dan, and Roddy each deal with this fact in different ways but each of their lives are profoundly impacted by it.

Mary feels particularly conflicted. She loves her mother, but at the same time she hates how controlling, unsupportive, and selfish she is. Mary wants her own life and wants to get away from her mother, but at the same time feels duty bound to take care of her. The war inside of her leaves her to a kind of paralysis that stops her from realising her dreams and instead keeps her by her mother’s side. Sinclair is pointing out that Mary is wasting her life trying to make her mother happy when she never will be and will never even minimally return any of her affection.

The emotional complexity that Sinclair details as well as the facets of this mother-daughter relationship that hinges on duty and disappointments is written masterfully and with an uncommon amount of insight — especially for literature of the time period.

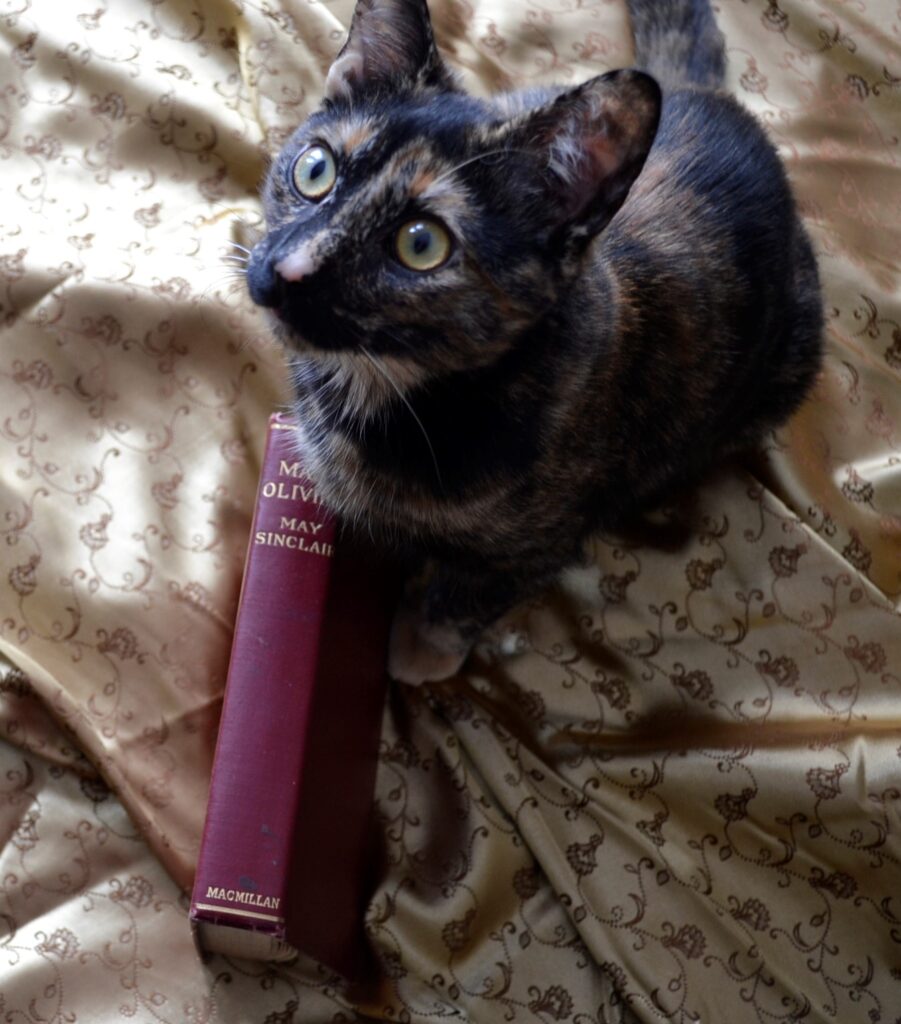

Part of the reason I love antiquarian books so much is that I can see how much they blazed a trail for the literature that followed and I always appreciate finding a novel that wasn’t afraid to discuss issues that were taboo at the time in which it was written.

My copy of Mary Olivier is a first edition from 1919 that I found in a bargain basement shelf in a large used bookstore. I bought it knowing nothing about it, but I’m so happy I took that leap of faith. New York Review Books published an edition of the novel in 2002, and I’m glad that they are keeping this work from disappearing into obscurity. Published alongside James Joyce’s Ulysses, Mary Olivier has an important place in the history of literature that shouldn’t be forgotten.

Victorian Sensibilities

One of the dominant themes in Mary Olivier is how much was left unsaid in Victorian family life. Familial affection was rarely expressed. There were subjects that weren’t talked about. Mental illness was unpleasantness that was kept as a deep dark secret. The Olivier family has three alcoholics in it and no one mentions where they are, that they are drunk when they are drunk, or the destruction they are reaping on everyone around them.

Sinclair touches on the various expectations that Victorian children laboured under. Their occupations were chosen for them — often based on nothing but gender and birth order. They often had to deal with unsubtle favouritism, cruelty, and belittling comments. The author describes just how destructive these things are and how much they can alter an individual’s destiny. She points out just how much pain these children went through and how they carried that pain into adulthood contrary to the Victorian idea that it somehow went away or was forgotten.

Knowing that makes this book a very powerful read indeed, and quite a statement about what kind of damage some malformed Victorian ideals had on an entire generation of children and subsequently adults.

Not Everything Changes

Even though going to the cottage gradually changed for me, my memories of the place remain the same. The pictures remain the same. Every once in a while, I’ll have a dream that is set there. I can still remember the feeling of the water or how the sunset looked on the lake. I can still remember my childhood and how it felt in those moments when summer was so long that I thought I knew what eternity felt like.

As an adult, I still am drawn to water. I’m glad that we live in a town with a river that we can take walks beside and see the ducks enjoying. Maybe someday I’ll see the lake again, and I’ll be able to see it as it once looked.