Nights Out at the Opera

One of the outings that myself and my lovely spouse enjoy most are trips to the opera. We love music. Listening to it, talking about it, seeing it on stage. Spotify is always playing in our house, filling our sitting room with everything from opera to jazz to lilting piano. We’ve been to the Met, and we’ve been to the Four Seasons Centre, and every time we sit there, side by side, in awe of the music and the spectacle that is opera, it’s so much more than just listening to music. It’s seeing it and letting it sweep over you in a way that is unique to the venue and the composition.

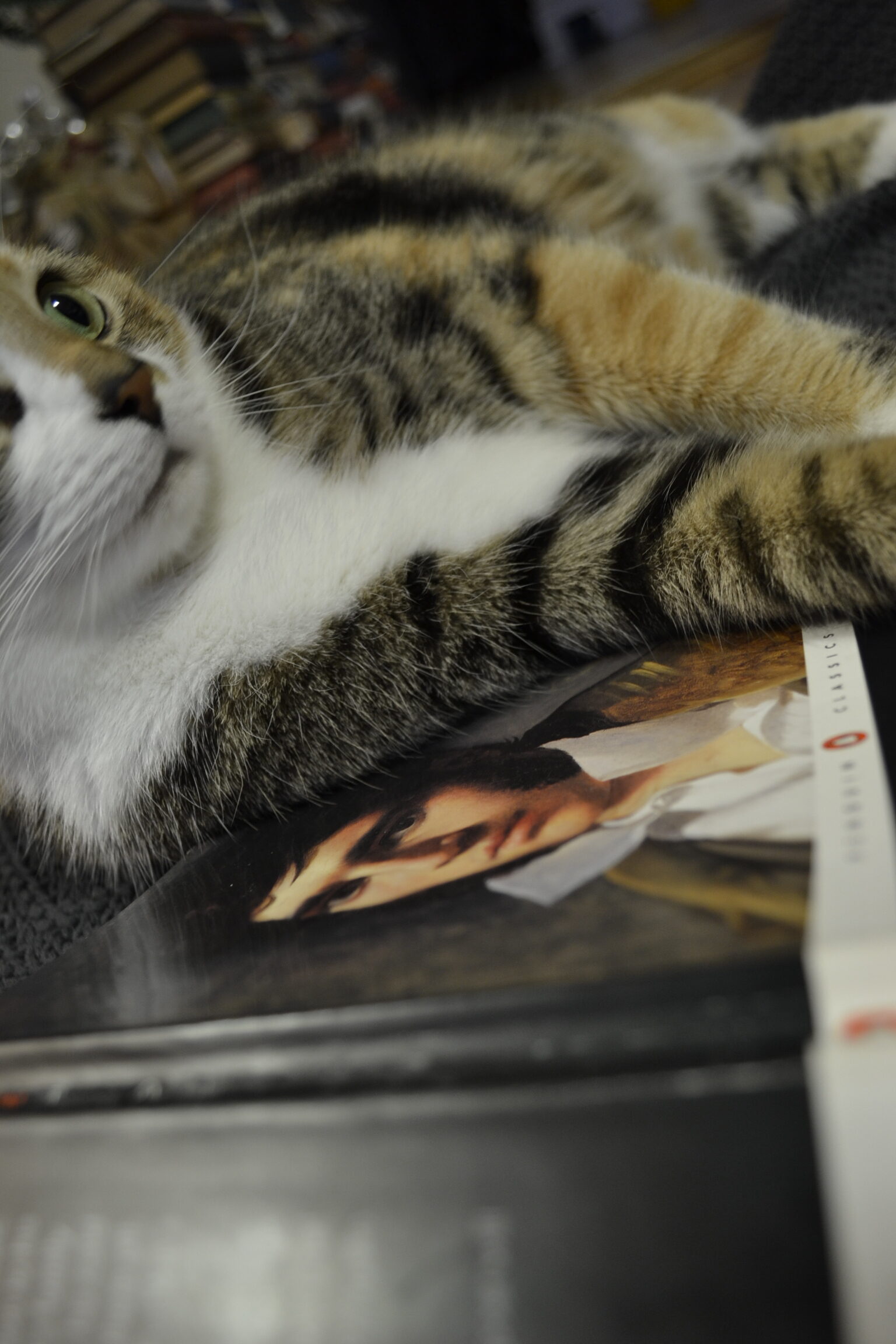

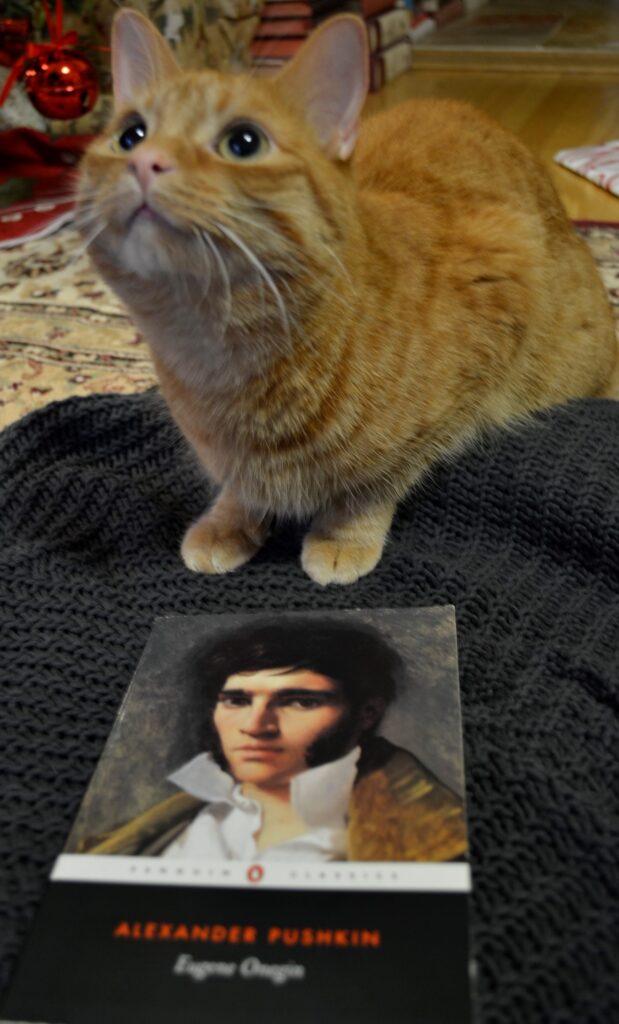

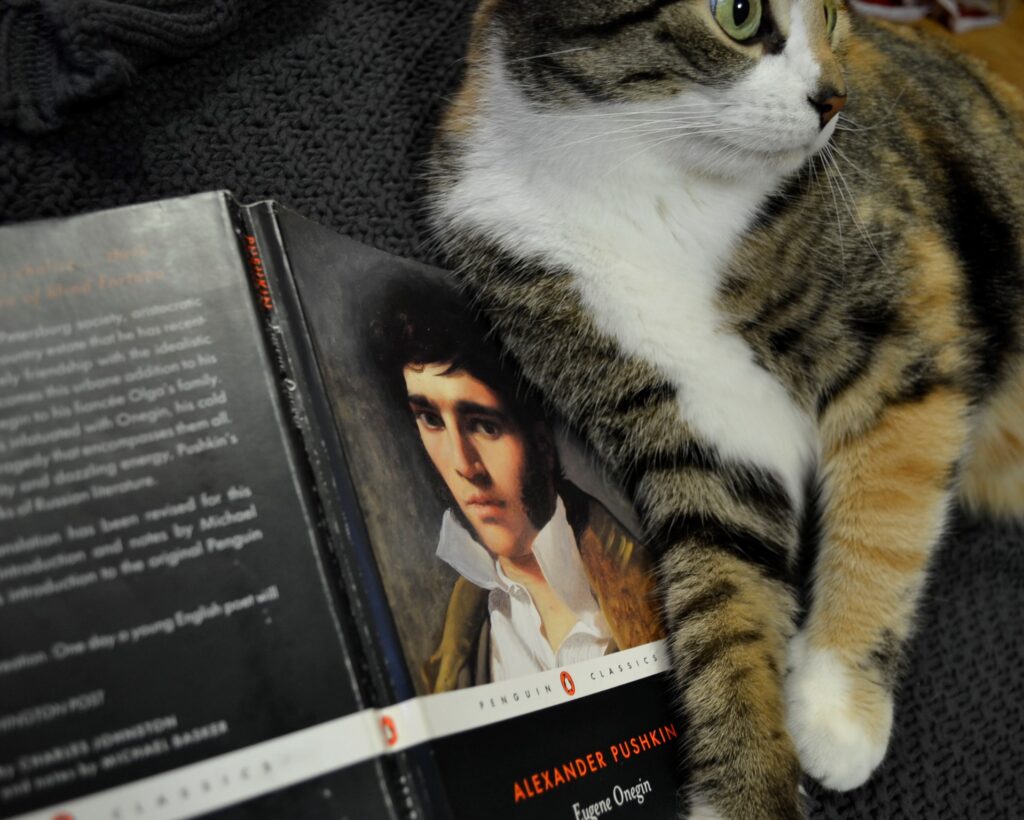

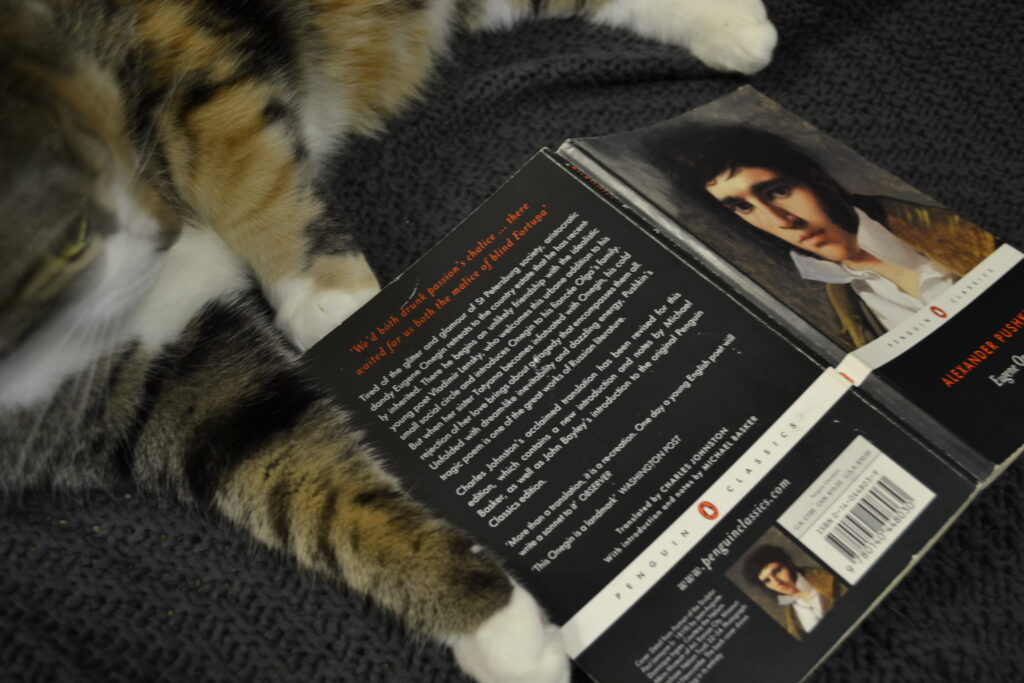

My lovely spouse and I have also seen operas far outside of the opera house, in live or repeat broadcasts in cinemas. That’s where we saw my favourite opera — Massenet’s Werther — and it’s also where we saw Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, which is based on the Pushkin novel. Even though we weren’t provided with subtitles to the Met’s production from 2007, the imagery and the music were capable of conveying the story in and of themselves. Whenever I see fall leaves in piles on the ground, I’m reminded of the set design.

A Novel in Verse

Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (Евгений Онегин) is actually a novel in verse which details the failed romance of Eugene Onegin and Tatyana Larina. Onegin is part of an aristocratic circle in St. Petersburg whose life consists of balls, intrigues, and luxury. He grows bored with his life and goes to the country only to be confronted with the rural version of the society he’s left behind. Tatyana falls in love with him but is rejected. Onegin instead pursues her sister, a duel ensues, and years pass. Onegin stumbles across Tatyana again and decides that now he will pursue her, only to be rejected in turn.

Pushkin’s narratives moves quickly but with an artistry and descriptive power that is unique to the author. Don’t let the fact that the novel is in verse intimidate you. The verse is not cumbersome or over complicated. It instead sets the pace and enhances the flow of the story to the extent that I couldn’t really imagine Onegin in a purely prose form. My edition of Onegin actually preserves the original rhyming structure of the verse, which is amazing. I would recommend looking specifically for that component when choosing a translation to read.

The Superfluous Man

The superfluous man is a concept in Russian literature of the 19th century. The concept is personified in a character that is aristocratic and educated, but who is selfish and useless to society, as he does nothing, accomplishes nothing, and lives an idle life full of balls and extravagances. Eugene Onegin is the archetype of this character. He’s selfish and self-involved and doesn’t think of anything outside of himself, what ball he is attending, and his image. In the end, he winds up alone and steeped in regrets from his life that has been wasted.

People are only pawns to the superfluous man and, when all is said and done, his end is one of loneliness, regret, and paying for his actions.

Why is it Essential?

The presentation of the superfluous man in Eugene Onegin was so effective that the archetype was retroactively applied even to characters from novels published before it, such as Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time. Eugene Onegin is essential because it represents a pivotal shift in Russian literature and is essential to the study of Russian literature in general. Pushkin is an author whose work continues to be discussed and to influence not just Russian writers but writers from across the globe.

Also, Eugene Onegin continues to be re-imagined in the form of plays, operas, ballets, musicals, and films. It is a work that is translated over and over again in multiple languages and is studied extensively by countless scholars throughout history.

Eugene Onegin is a work that will be continue to be read long into the future and that one who studies literature should have in their to-read stack no matter what their particular specialty may be.

Nights In at the Opera

This year, our nights at the opera have looked a lot different. We don’t go out to the opera. Instead, the opera comes to us via our laptop and the Met’s free nightly streaming program. We sit on the couch under our favourite throw blanket, get out the popcorn, and enjoy the music. In some ways I like opera even more this way, because it’s a more comfy, cozy experience. We’re also getting the chance to see more performances than we could ever afford to see in person. This year alone we’ve seen Peter Grimes, Pagliacci, Lucia di Lammermoor, Salome, Manon, and Die Walküre — just to name a few. But, of course, I always miss going to the opera house at least a little bit.

But it won’t be forever. Someday there will be trips to the theatre, and the opera house again. In the meantime, it’s best to enjoy the moment and be grateful to be healthy, happy, and comfortable in our little house in our little theatre town.