Watching for Rain

The weather in the last week has felt very apocalyptic in a lot of ways. We were fortunate enough to be far away from the wildfires, but I extend my deepest sympathy to anyone who was affected by them. It was scary enough just seeing the haze in the sky and staying inside in order to follow all of the air quality warnings — I can’t imagine what it was like to live in the areas most affected.

It’s been so dry that lawnmowers in our neighbourhood are mostly churning up dust with a bit of straw in it. We’ve been watering the plants, but leaving the grass to itself and hoping that we’ll get rain soon. It’s been a long wait. And a lot of looking at the weather app and sighing when things change and showers get further away. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to like the rain and to appreciate all of the wondrous things it does to the landscape and life in general. Droughts no longer mean more days for the child that I once was to swim in the lake. Droughts mean worrying about plants and crops and wildlife. Droughts are worrying about fire. Droughts are watching for the sky to darken. Droughts are waiting for rain.

The Confessional Novel

The confessional novel as a genre began with literature taking a cue from confessional practices linked to religious practices. In the eighteenth century, Rousseau published his Confessions, but one could also find historical roots in Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions as well. Narratives in confessional novels use a style and structure centred on the narrator’s inner secret emotions, revelations, and immoral or subversive behaviour. This style of novel has roots that are centuries old, but really blossomed in the Modern and Post-Modern era and is still popular in contemporary literature.

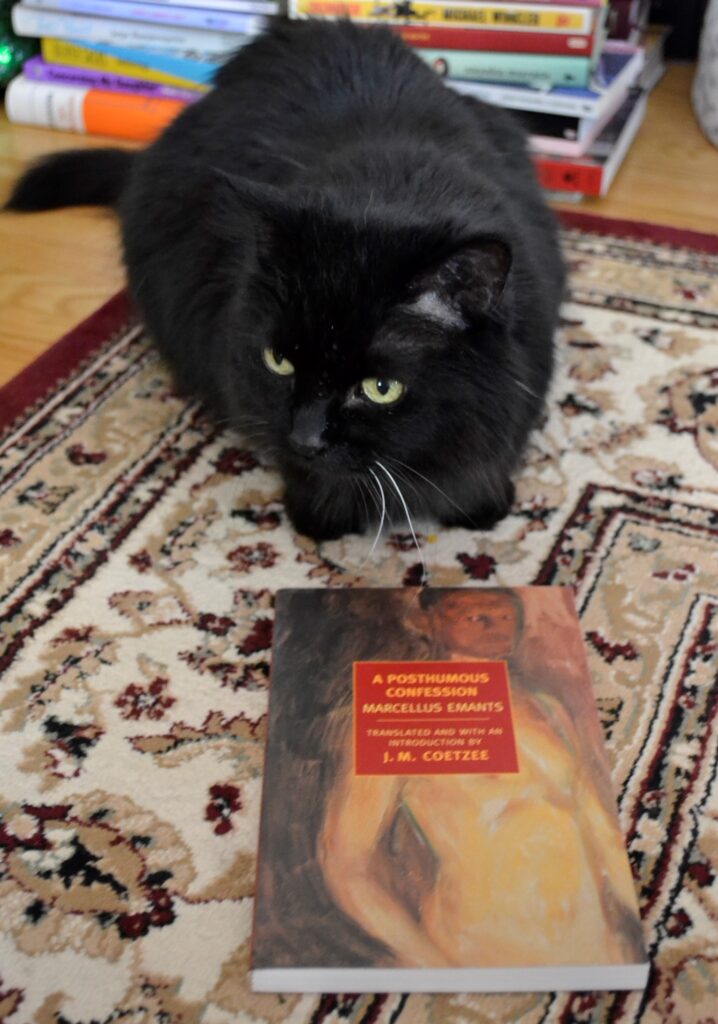

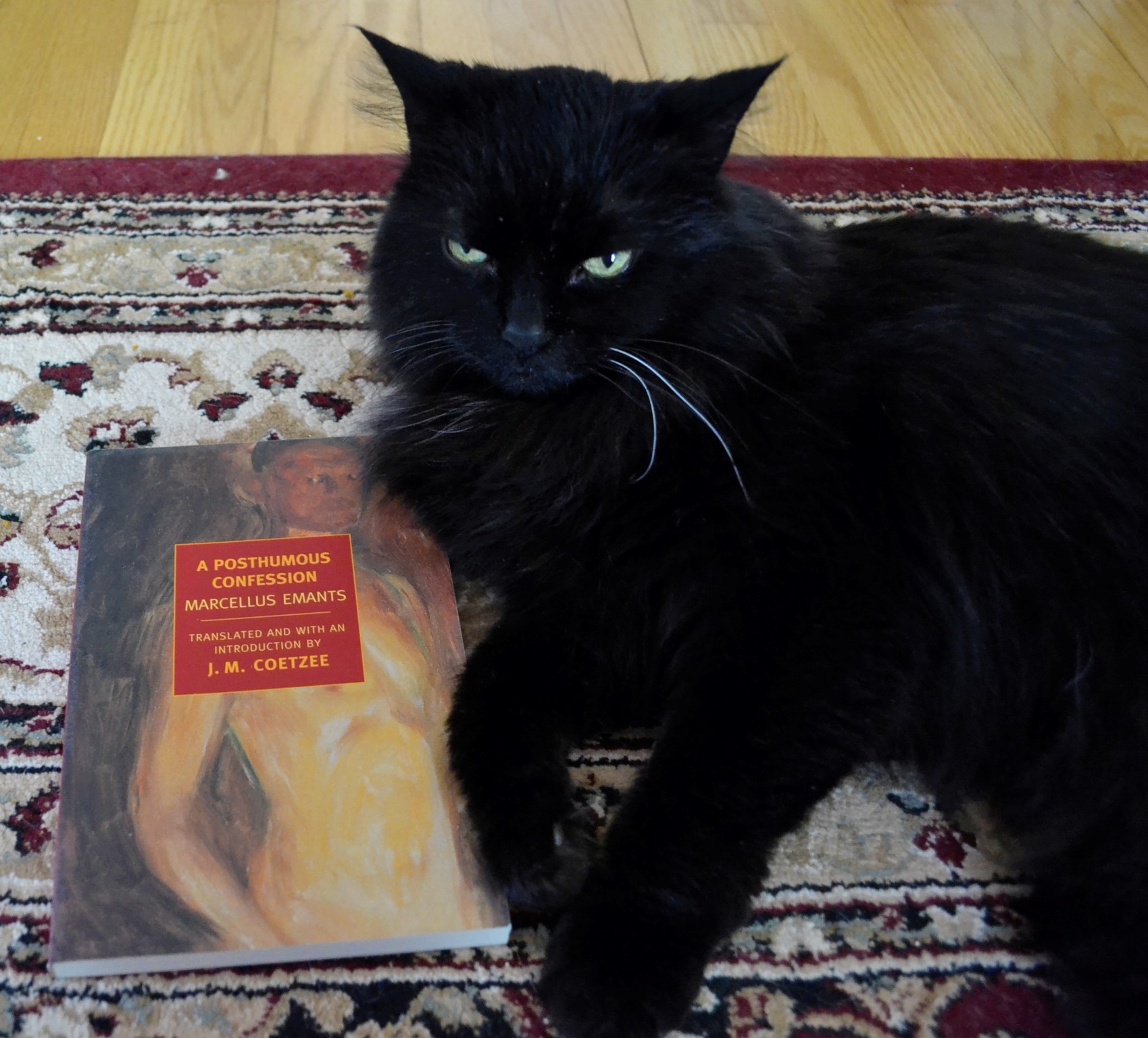

Emants’ A Posthumous Confession is indeed quite a pure example of a confessional novel — the back copy of my NYRB edition does not lie. Termeer is a man who cannot experience empathy and who is crippled by cowardice. He makes decisions based on whim, gain, and societal expectations and he is continually miserable because of it. Then he gets married and is even more unhappy than he was before. The solution? He murders his wife. The book serves as his confessor to all of the thoughts, feelings, and parts of his history that he cannot utter out loud to any other human being. It is Termeer writing away his urge to confess what he has done to anyone he bumps into.

A Dissection of a Marriage?

I honestly thought that the book would be more about Termeer’s marriage to Anna, the daughter of his financial guardian. But I think the real meat of the narrative has to do with Termeer speaking to the reader about who he is and what factors in his life formed him (in his own opinion). Most of the page count is racked up before he even meets Anna or her family. While the content isn’t exactly dull and the writing style is masterful, I was left with the feeling that Anna is not really much a part of a story that is supposedly focussed on her. Termeer’s childhood and the incidents in his life leading up to his marriage were important for developing Termeer’s character, but this was perhaps a case of too much development and too much word count in what is otherwise a very concise book.

However, Emants does use this overinflated beginning to further illustrate how self-involved, self-important, whining, and cringing Termeer is — so I can’t say that it isn’t done for an effect that ends up being very successful.

Noir Overtones

Termeer is a horrible man that marries a women he doesn’t love, kills her, and then he astonishingly gets away with it only to be wracked by a very shallow yet nagging guilt. Yes, you might see some similarities with Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment here. However, Termeer does not feel any real sense of remorse. In fact, in the end, he doesn’t at all change any part of his behaviour. His is no dark night of the soul. He’s a horrible man who did something horrible and does not in fact care about his act, the destruction of it, or what it means in terms of his own monstrosity. Instead, he simply goes back to a mistress that only wants his money, in the false hope that she must love him somehow.

It reminds me of the plots of some very compelling noirs, actually. And while I know this is published far too early to be a part of that genre in the truest sense, the novel does resonate as a crime story. The caveat being that the crime is not as detailed as it should be to truly fit with that notion. But even the ending is so beautifully bleak and hopeless.

In short it makes me want to break out all of the Mitchum and Bogart films I can and escape into reruns of TCM’s Noir Alley for at least a day or two.

The First Few Sprinkles

This morning my lovely spouse went out to feed the birds for me and we were both grinning as she told me she could feel some raindrops. It’s not the downpour I wanted (or that the vegetation clearly needs), but it’s a start. Plus I am heartened by a week of rain in the forecast.

I can’t wait to see the grass get green again. I just may have to restrain myself from going outside barefoot in order to feel some of the dirt turn to mud between my toes.

As a side note — Rusalka is the only one of our cats that actually likes being out in the rain. Not pouring rain, but she does like getting sprinkled upon every once in a while.