Used Does Not Mean Cheap

One of the first things you should know about the wide world of antiquarian and rare books is that, though they may be used, they will not necessarily be cheap. Yes, there are those rare bargain basement finds that sometimes happen, but for the most part, you can pay either the same amount as a new book or sometimes more for what many would consider to be a ‘used’ book.

You’re paying for a book that is more than that. You’re paying for a little, rare piece of history. I can’t describe the feeling of holding something in your hands that a fountain ink inscription tells you someone got for their twenty-first birthday in 1922. You’re paying for beautiful plates drawn by talented artists. You’re paying for printing that wasn’t digital. You’re paying for something you can’t get at a big bookstore.

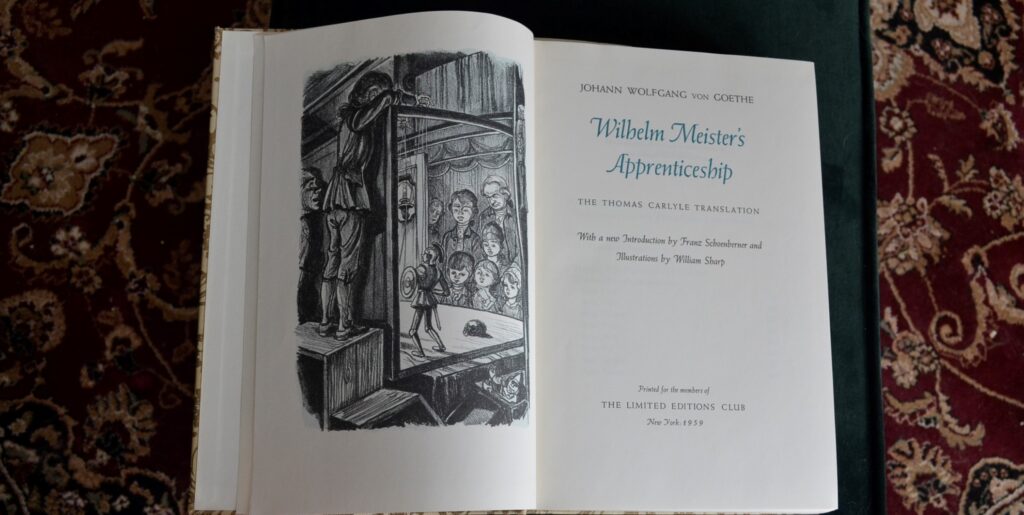

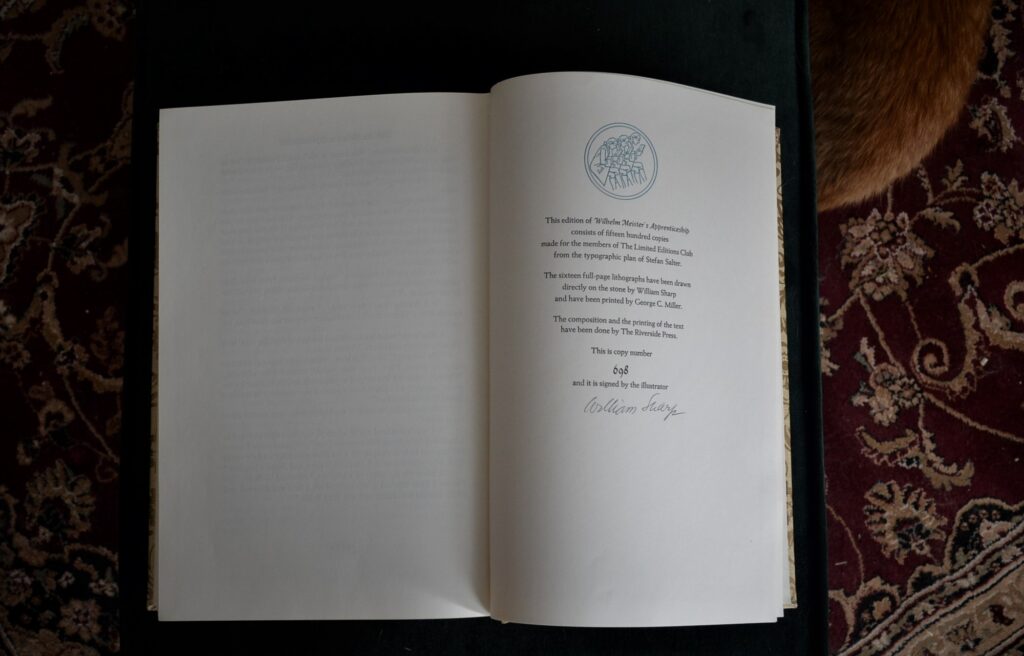

My particular copy of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre) was by no means cheap, nor should it have been. It was published in 1959 as part of the Limited Editions Club — limited to 1500 copies and signed by the illustrator, William Sharp. Beautiful binding, beautiful full-page plates combined with simpler illustrations throughout, it’s an amazingly pretty book.

I was impressed with it as soon as soon as the bookseller brought it out from amongst all of the other rare volumes at the back of the store. My spouse bought it for me as soon as she saw my eyes light up on seeing all of the plates.

And so I read Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship.

A Note on Ease of Reading

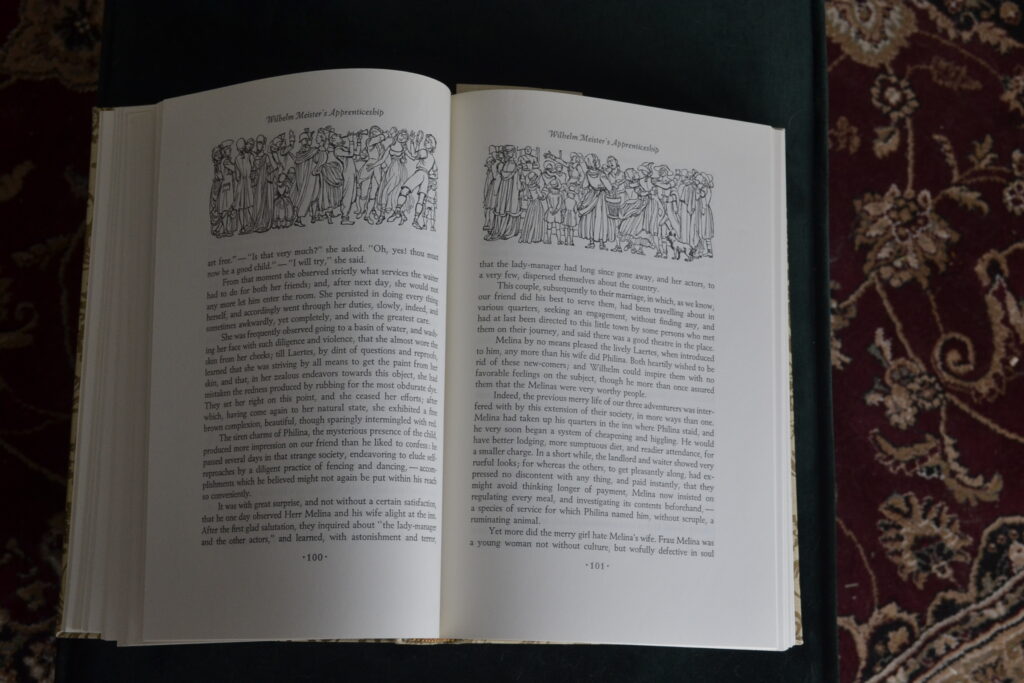

Obviously, this book is a little larger than your typical Penguin paperback and thus it can be a bit cumbersome to get comfortable in your favourite armchair whilst reading it. Specifically, I always find that I have to keep shifting my hold on the book because the pressure on my wrists makes my fingers go numb after a while. I set the book on the arm of my chair and lean over it but then my neck gets stiff.

All of these problems are worth the pure luxury of reading an edition like this, though, and I’d hate to see the illustrations squashed into a smaller format.

Bildungsroman

Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship was a pioneer work of bildungsroman. In the story of Wilhelm Meister and his quest to become an actor and his disillusionment with the experience of being one, the novel follows the overall structure of a ‘coming-of-age’ narrative. However, it goes beyond that — in the sense that Goethe includes several dialogues on several different topics and studies. He presents theories on the studies of literature, science, theology, and comments on class distinctions and economics as well as the merchant trade, property inheritance, estates, the running of households, and the list just keeps on going.

Reading Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship is like reading both a novel and a textbook at times, with long speeches on very varied topics that stray into the instructional. Admittedly, it can make for some tedious passages.

What I really enjoyed most about this book? I got a chance to learn a lot about the business of running and working in a theatre in the eighteenth century. Goethe was the managing director of a theatre himself and he details extensively what’s involved in procuring engagements for troupes, contract renewals and contents, rehearsals. He even draws a contrast between more professional and less professional companies of actors and their several procedures.

One of the reasons I read classics is to learn about history and daily life in different time periods, so I appreciate a work that allows me to study an aspect of that so minutely.

The More Things Stay the Same

As an amusing aside, there’s a passage in Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship where Goethe is complaining about the printing press inundating the public with subpar writing.

A young author, who has not yet seen himself in print, will, in such a case, apply no ordinary care to provide a clear and beautiful transcript of his works. It is like the golden age of authorship: he feels transported into those centuries when the press had not inundated the world with so many useless writings, when none but excellent performances were copied, and kept by the noblest men; and he easily admits the illusion that his own accurately ruled and measured manuscript may itself prove an excellent performance, worthy to be kept and valued by some future critic.

It reminds me of the arguments about the internet, ebooks, and self-publishing, almost exactly proving that history has an uncanny way of repeating itself — sometimes in unexpected ways.

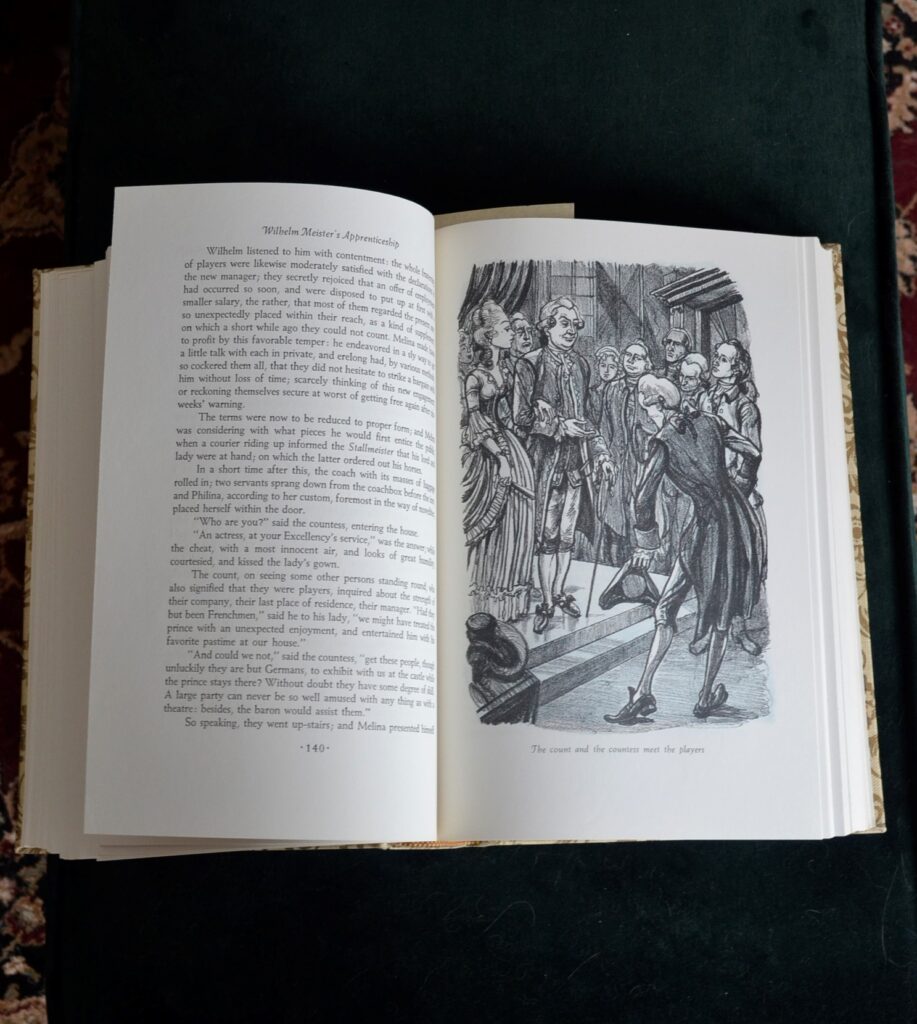

A Note on Illustration

Beautiful plates can really bring a book to life and William Sharp’s illustrations in this edition do just that. He has a style of drawing historical clothing and scenery that renders it close enough for the reader to touch. A way of making the distant age ordinary so that the reader can think in terms of the mechanics and mundanities of ordinary people living two and a half centuries ago rather than the characters seeming lofty or classical. The plates really compliment the goals of Goethe’s novel perfectly; they neither distract from nor do they overshadow the text.

Are You a Collector?

The bookseller who sold me this book asked me if I was a collector, and long after the store I was still thinking about the many facets of that question when it comes to rare books. I answered no because I can’t afford to buy the very rare, very beautiful editions that are only in reach to those with unlimited budgets.

However, I am a collector in the sense that I try my best to stock my library with a wide breadth of work and in the sense that — when the opportunity arises — I am choosy about which editions and translations I purchase.

It’s an eclectic collection. I have books that were translated into English and printed once in 1922. I also have some newer sets of volumes that I chose because I liked the printing. Of course, every once in a while, I do enjoy splurging a bit on one of the more expensive editions and they take a special place on the shelf where I flip through them whenever the mood strikes me. To some extent I would have to say that almost every person who is acquainted with antiquarian books is a collector of some persuasion. Half of the fun is the evolution of the collection and the form it take