When It Rains

This week has been a minor version of hell, and I don’t think I’m exaggerating this time. My lovely spouse lost a family member. A family member of mine is having health issues and will need my assistance soon. Rain, lots of it with thunderstorms, is coming and that makes me so upset and frightened and picturing more repairs and more chaos.

So I went a bit excessive with the weather apps this week and gave myself another migraine and am in no way prepared for more family to visit in the next few days. It’s time to put down the weather doomscrolling and actually do a little self-care. Get some sleep. Read some happy things. Remind myself that even when it feels like life is hurling lemons at you from one of those tennis ball machines and it’s scary, it won’t be like this forever. Feelings are like the weather. They are not the climate.

How to Live

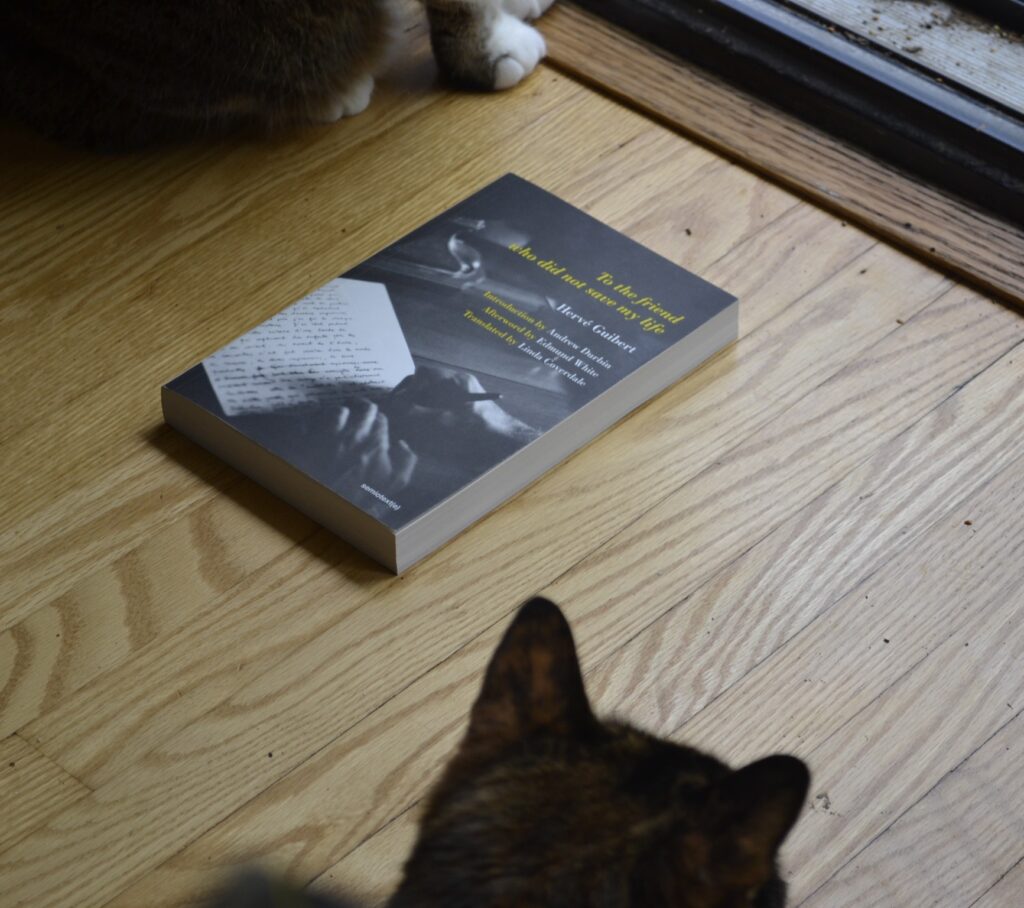

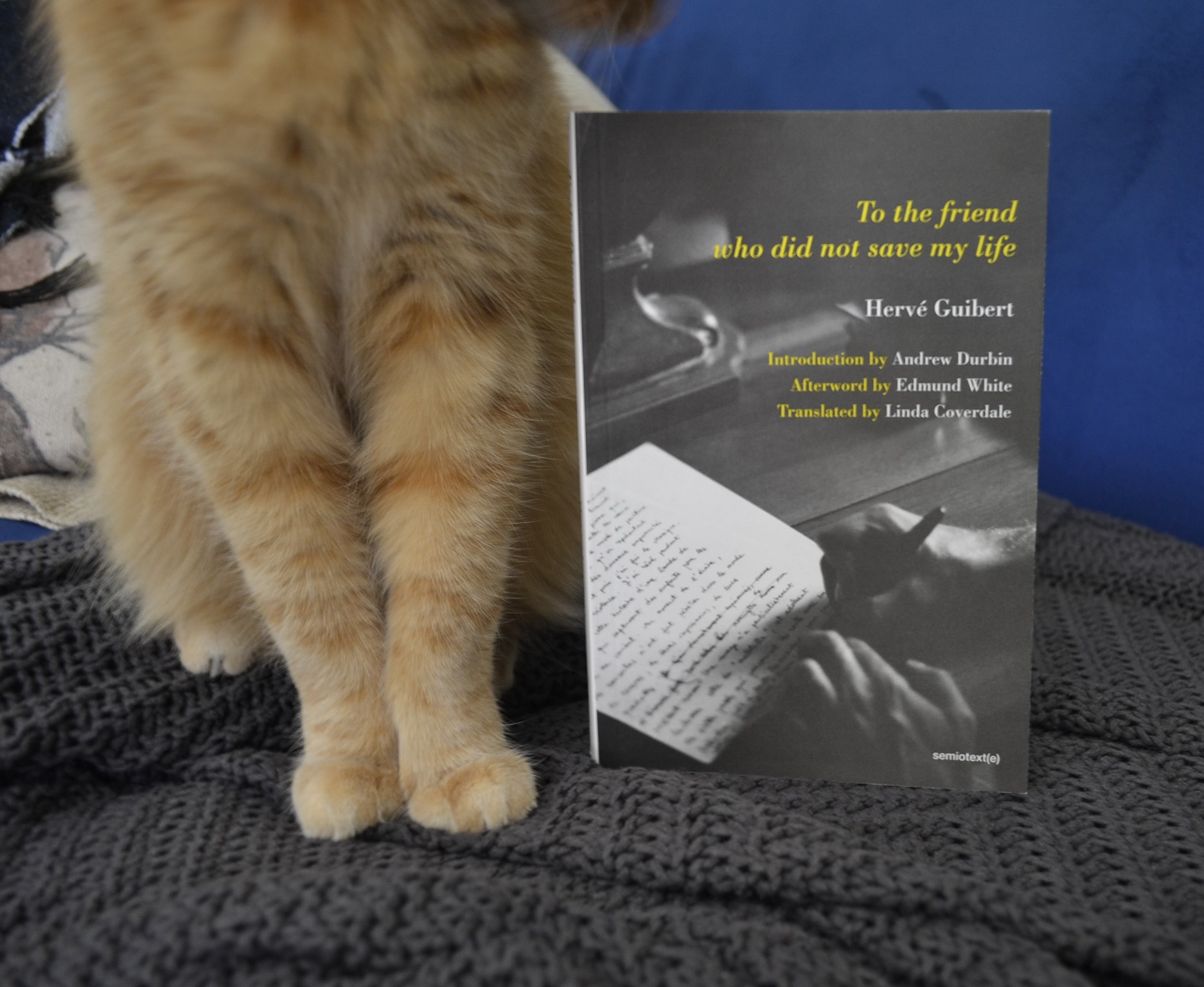

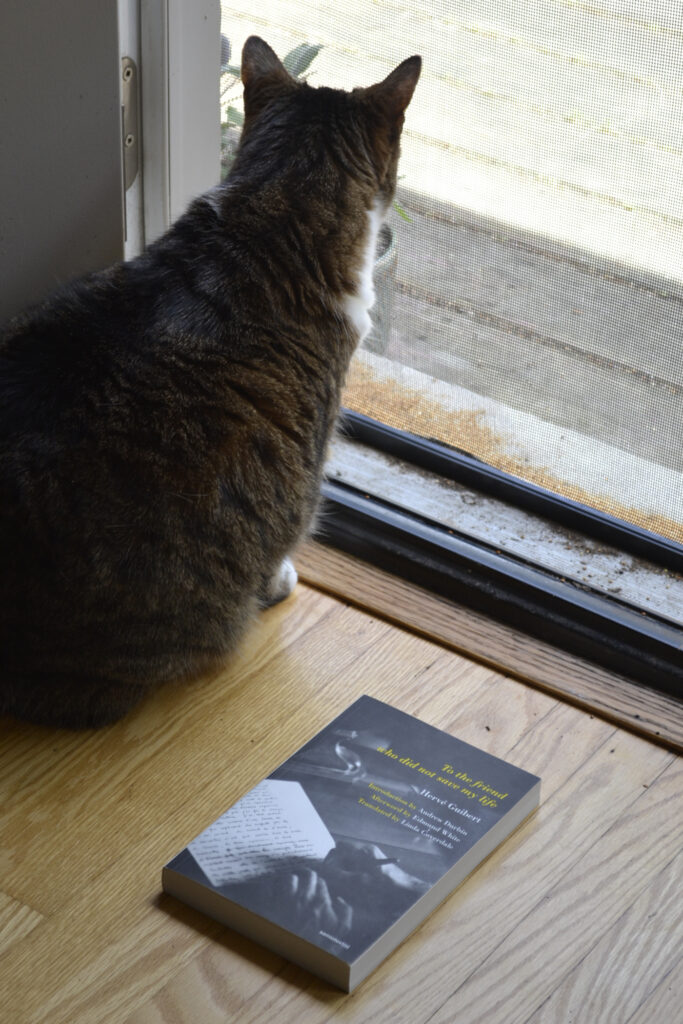

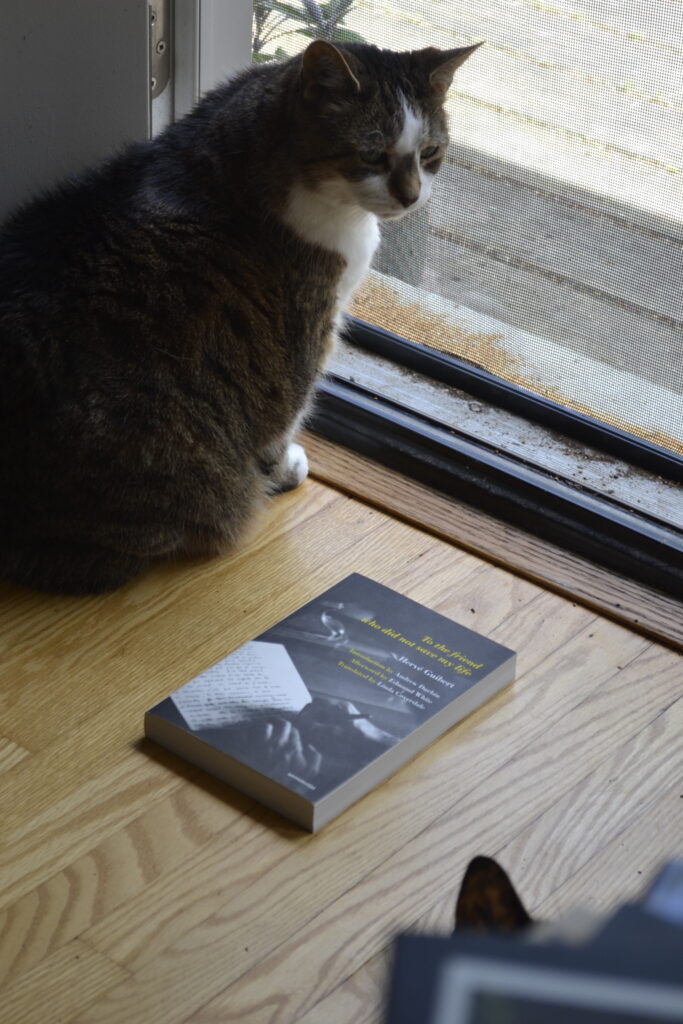

Herve Guibert’s book To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life made a big impact when it was published in France in 1990. There are several reasons for that. The first is that French media was scandalized to recognize Guibert’s friend ‘Muzil’, who is a major character in the book, as the very famous Michel Foucault. Guibert was propelled into the spotlight and the work became a bestseller. It’s a very honest account of Guibert’s experience getting diagnosed and treated for AIDS as well as what his close friends went through as he watched helplessly.

It’s an account that isn’t without humour and a balance of the harrowing moments with those of near absurdity. While it might sound like a difficult read, it isn’t. Guibert’s voice remains strong even as his body is starting to weaken and more fear dominates his days. The structure in itself is also compelling as the narrative unfolds in a series of shorter and longer vignettes.

How to Die

The reader follows Guibert to his medical appointments and stands next to him for both bad news and good. For hopes and crushing realizations. Guibert fears death and the kind of death that AIDS causes. He debates whether he wants to take control and end his life on his own terms. He struggles alternately with the impossible belief that he will somehow survive, and the grim reality that he doesn’t know how much longer his quality of life will endure.

In the midst of all this are beautiful comments on what makes life worthwhile and all of the things that are worth holding on to for as long as possible. While Guibert desperately hangs on to every moment and every scrap of laughter and sunlight, the reader realizes just how precious they are.

A Note on Style

As I said, this book is best described as a series of vignettes, but there is a through line struck amidst them — that being the friend who does not save Guibert’s life. This friend is an American that supposedly has access to a miracle drug or vaccine that will hopefully be the cure to AIDS and Guibert’s salvation. It is what Guibert stakes his hopes on in his darkness moments. But as this hope evaporates, Guibert is left with the ashes of the future which he knew all along that he wouldn’t get to enjoy.

While the book takes its name from this series of events, I wouldn’t say that they are what make the book or are even the main focus of it. Instead, this is really about Guibert and his diagnosis with a lot of insight into the medical system of the time and the procedure of treatment. It is about what it feels like to be given the death sentence that was AIDS in the 1980s, and, really, it’s about life that carries on. No matter what.

It Has to Get Better

I know that it will get better. That I won’t feel like this forever. But everything in me wants it to get better, faster. I cannot rush the randomness of the universe, but, wow, I want to.

Therapy has shown me that I have a lot of problems with patience and the quest for certainty, always. That’s never going to happen and I need to accept that. And again, I need to stop checking the weather apps because that is not the same as certainty, no matter what my brain is trying to tell me.