A Uniquely Antiquarian Problem

There are some problems that only happen with antiquarian books. Namely, that sometimes you can collect a single work in bits and pieces. Yes, that book that looks so interesting may not be one book at all. It may be just the first half of that book, or the first published piece of that book, or some alternative and incomplete version of that book — and then there you are with a very annoying problem.

Granted, I suppose one could just forget about the book in question and give up, but that wouldn’t be very fun would it?

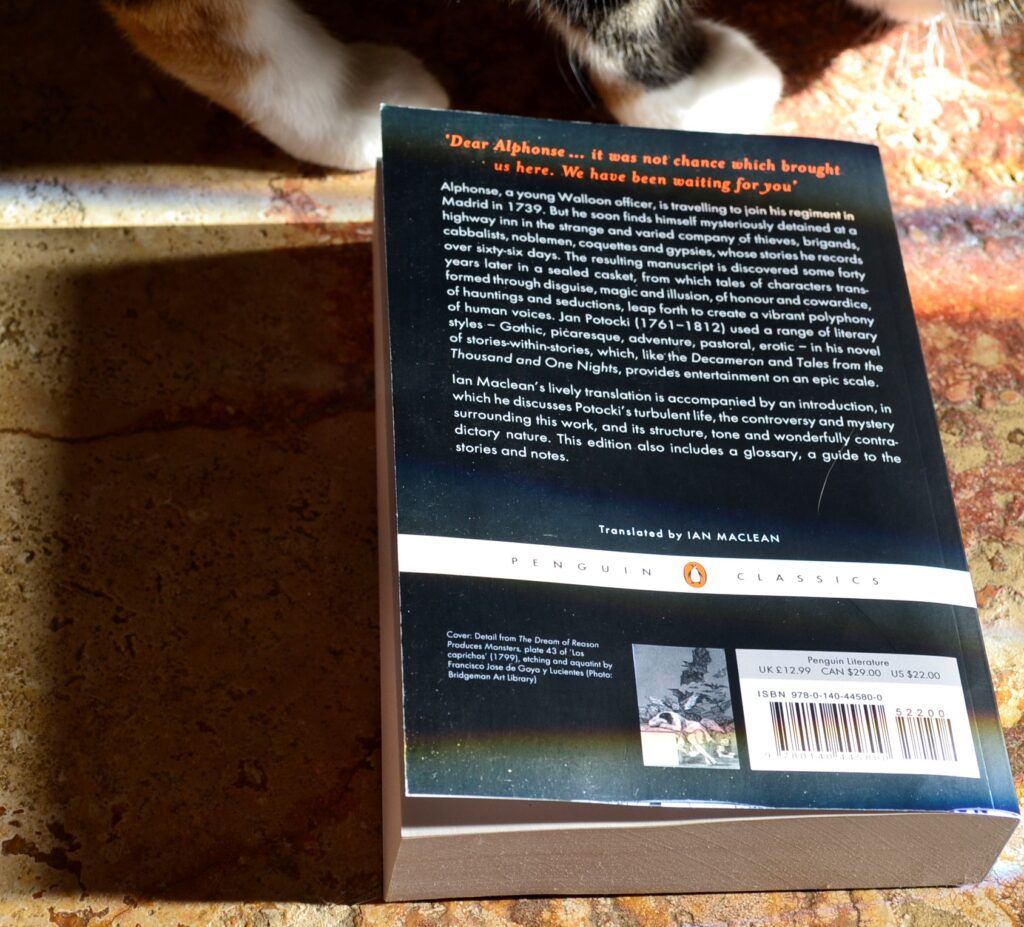

The Manuscript Found in Saragossa (Manuscrit trouvé à Saragosse) was recommended to me both because I was trying to read more work from Polish authors and because I have read Boccaccio’s Decameron. (The Manuscript Found in Saragossa is also sometimes called The Saragossa Manuscript or The New Decameron.) I didn’t much like the Decameron, but I do like a collection of short stories and I had hopes that Potocki’s attempt at the Decameron’s format would be better.

However, when I got home and opened the cover to read said volume, I realized that the narrative started at Day Fifteen.

Oh.

No.

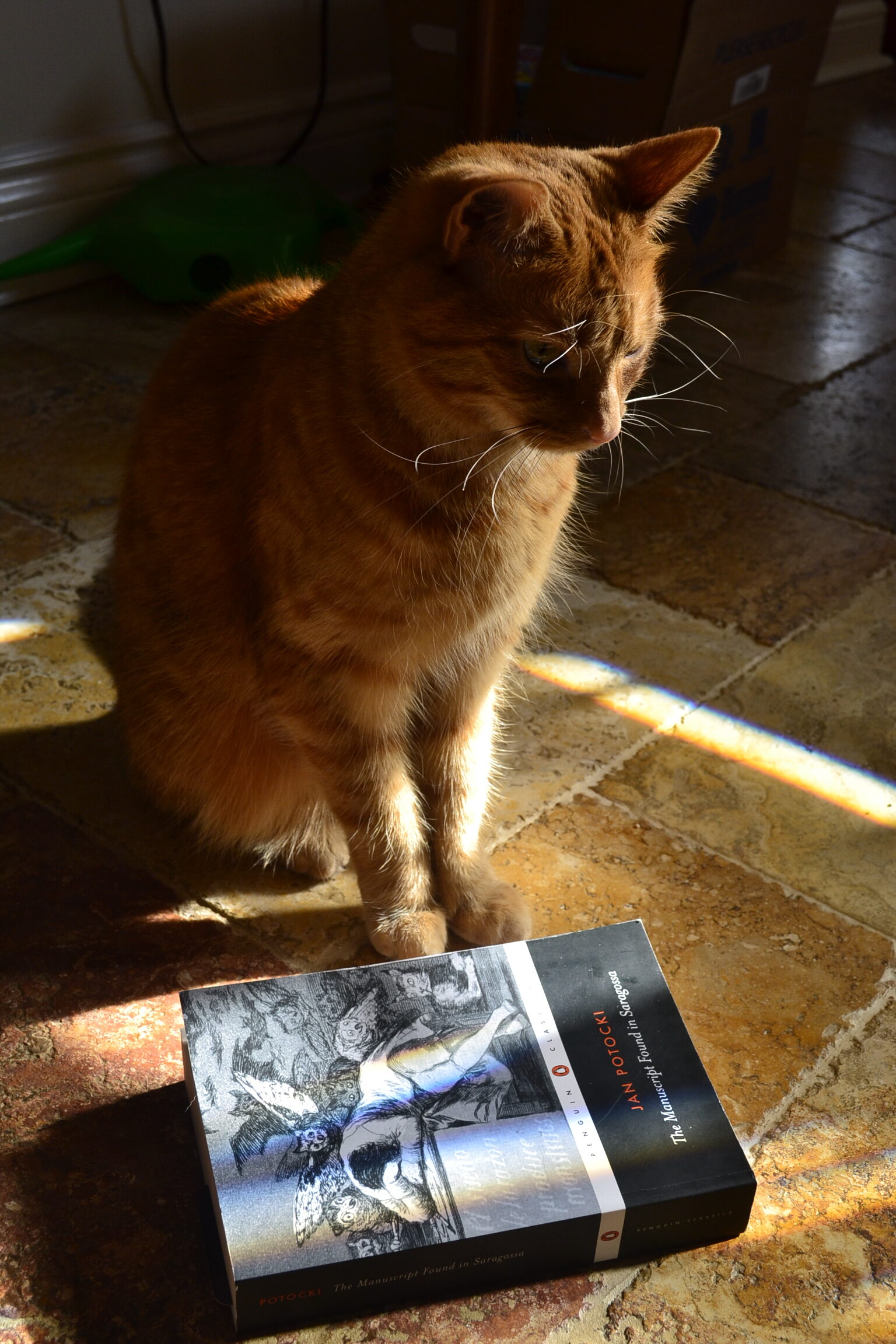

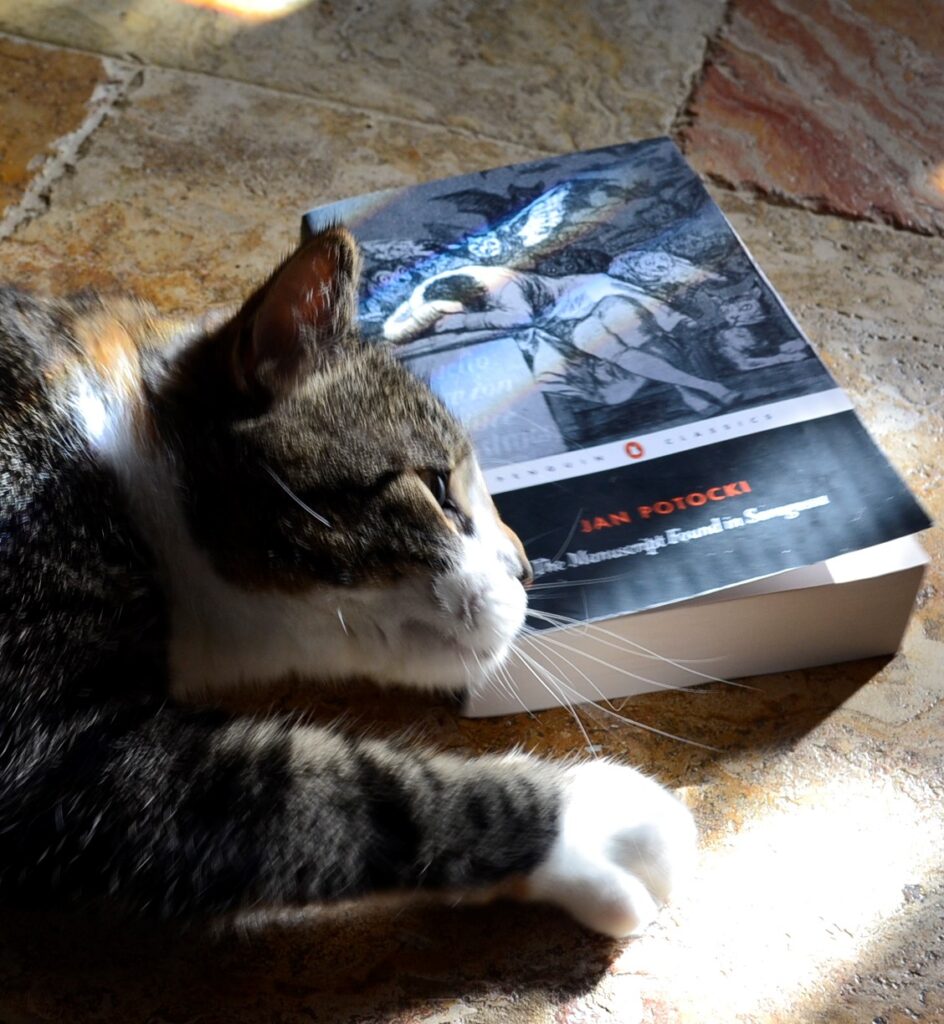

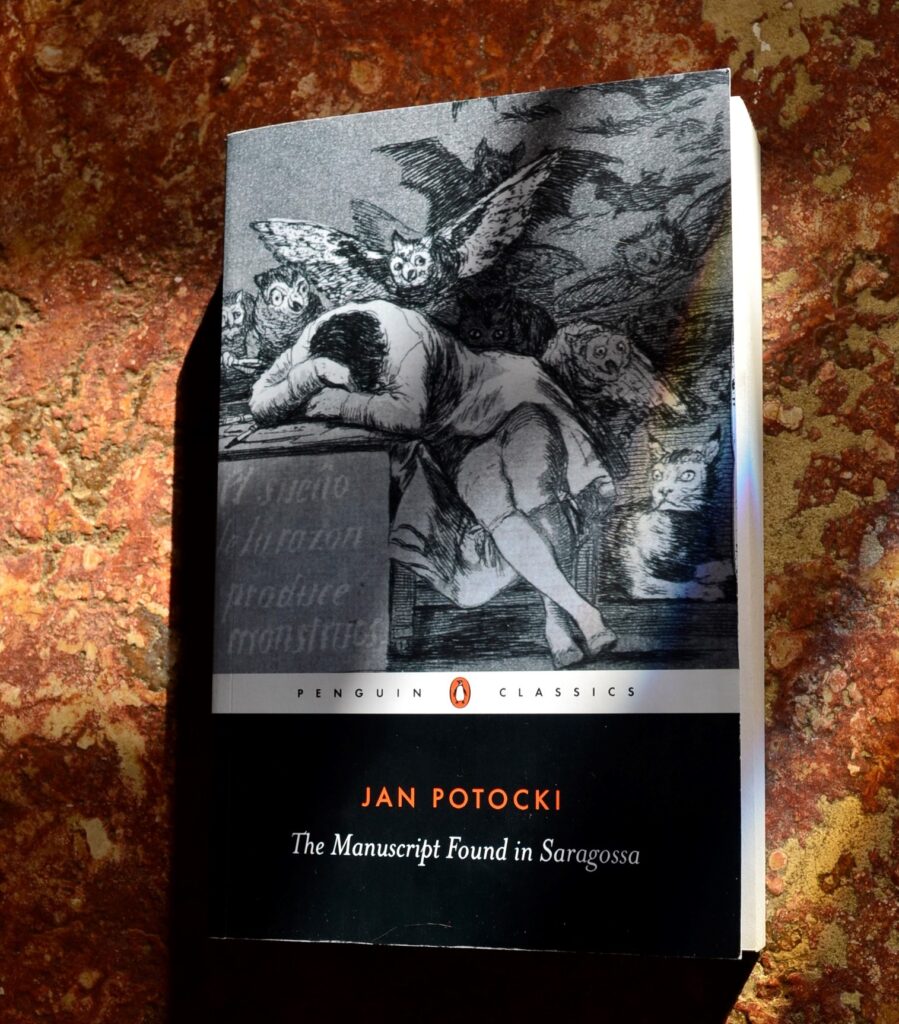

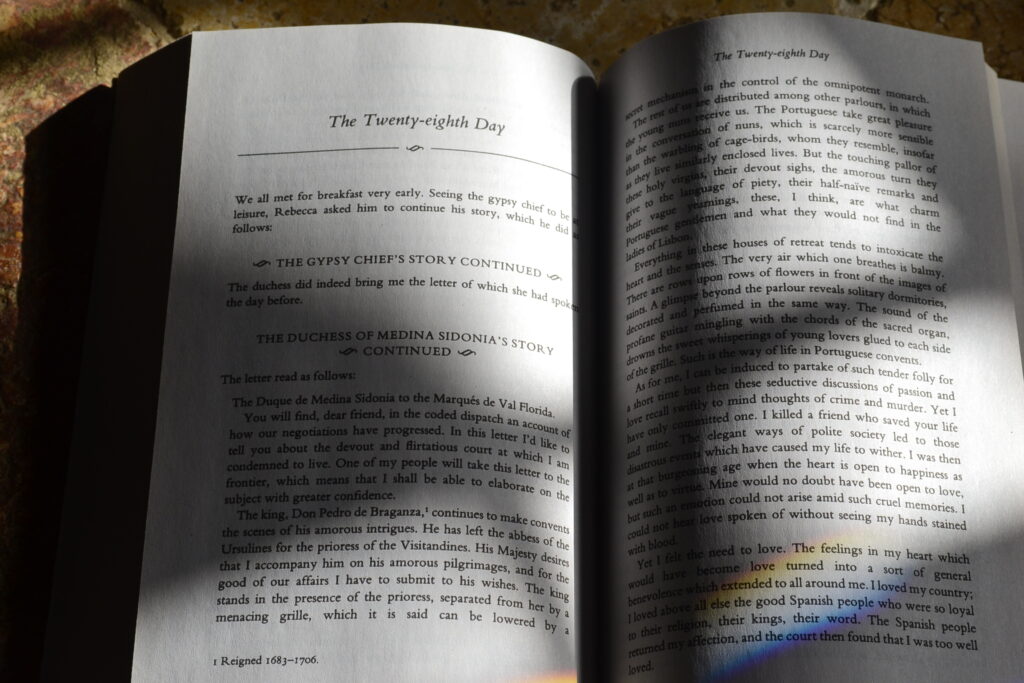

I thought about giving up, but once I read a bit about Potocki’s biography, I decided to resort to looking for a complete copy online and was happy to find the Penguin Classics edition, complete with Goya’s The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters on the cover.

Mission accomplished.

Sixty-Six Days in the Sierra Morena Mountains

The Manuscript Found in Saragossa is a six-hundred and thirty-page novel in which Alphonse, a young officer, is sidetracked on the way to find his regiment by gypsies, thieves, a mathematician, and others who entertain each other with stories in their attempt to get to the bottom of a possible haunting of gallows corpses.

Like Boccaccio’s Decameron, the novel is separated into days and is structured around the telling of various stories. Potocki’s subject matter and interests are varied and he includes tales about science, religious, aristocracy, demons, and even math and ancient texts.

A Word on Count Jan Potocki

Other than general information to help put the work in context, I am not usually drawn to the biography of a work’s author. However, Count Potocki is an exception — not so much because of how he lived, but more so because of the circumstances surrounding his death.

A wealthy man from an aristocratic family, Potocki had the luxury of travelling the world widely when a lot of people never left their respective villages. That travel is apparent in his writing but what is also apparent are the factors that lead to his death. In 1812, Potocki retired to his estates in Poland suffering from various mental illnesses and health problems. In 1815, he committed suicide by fashioning a silver bullet and firing it on himself because he believed that he was becoming a werewolf.

Suffering from mental illness myself, I’m always fascinated to read work from those suffering from mental illness at points in history when much of the workings of the brain was utterly unknown and treatment either non-existent or utterly barbaric. Potocki’s work has a frenetic quality to it as well as an obsession with the occult and mysticism. Knowing the nature of Potocki’s death, one can see how the disorders of his mind influenced the world he created in his manuscript and the twists and turns the storytelling takes. At times this adds life to what he’s writing, but at times it comes at the reader as a rush of ideas that seem fragmentary. There are some loose ends of plots that are abandoned and others that I would argue are carried too far.

Stories Within Stories

Potocki’s manuscript goes above and beyond the Decameron by including more than a set amount of stories each day. Instead, the stories are nested together to make stories within stories within stories, like a matryoshka doll. It’s easy to get lost in the stories and their overlaps, but usually it is in the most pleasant way.

That being said, I would recommend not putting this book down for days at a time or you risk forgetting which layer you’re currently reading.

It’s a structure that can be challenging, and Potocki almost makes it look utterly effortless. However, there are other structural problems that become painfully obvious. For example, at one point a story involves a hundred-volume work that details the extent of human knowledge. Potocki lists what each volume contains — which takes three very, very lengthy pages.

Classification

I initially found this book because I wanted to read more work from Polish authors, but I’m not sure Potocki gave me any further understanding of Polish literature. His writing isn’t tied to any region other than Potocki’s version of Spain. But, beyond that, it’s a work that isn’t tied to any kind of realism. Potocki is writing something for the reader to escape in. A world of magic, mysticism, and the storytelling tropes and clichés that audiences he would have known consistently enjoyed.

Potocki is trying to tap into something universal (albeit in a very limited, eighteenth-century, wealthily aristocratic, woefully limited way), and though he wasn’t the author I was trying to read, I did enjoy the journey the book took me on nonetheless.

Parting Thoughts

Would I choose to read this very large book again? Yes, I would. Though I will warn that though this a slightly weirder Decameron, it is still in essence a Decameron. Knowing that will keep your expectations under control. This is not a novel rife with meaning and flowing prose. It’s a whole different kettle of fish, and it’s much better that way.

If you want a piece of 18th century escapism, then this book will not disappoint — though, honestly, I admit I still prefer Laurence Sterne.*

Some Problems Remain Unavoidable

I’m sure The Manuscript Found in Saragossa is not the last book that I’ll buy in bits and pieces. Part of the fun of collecting and reading old books is the variations in editions, versions, and publication history. My partially complete copy and my complete copy of the manuscript will sit next to each other on my bookshelf.

Hopefully I don’t run into this particular problem often, but when I do, I’ll shrug and sigh, and look for another copy.

* Yes, technically, this book is 19th century/Romantic era in publication date. But Potocki’s attitude and the book itself are very 18th century in mentality — and he did begin writing it in the 1790s.