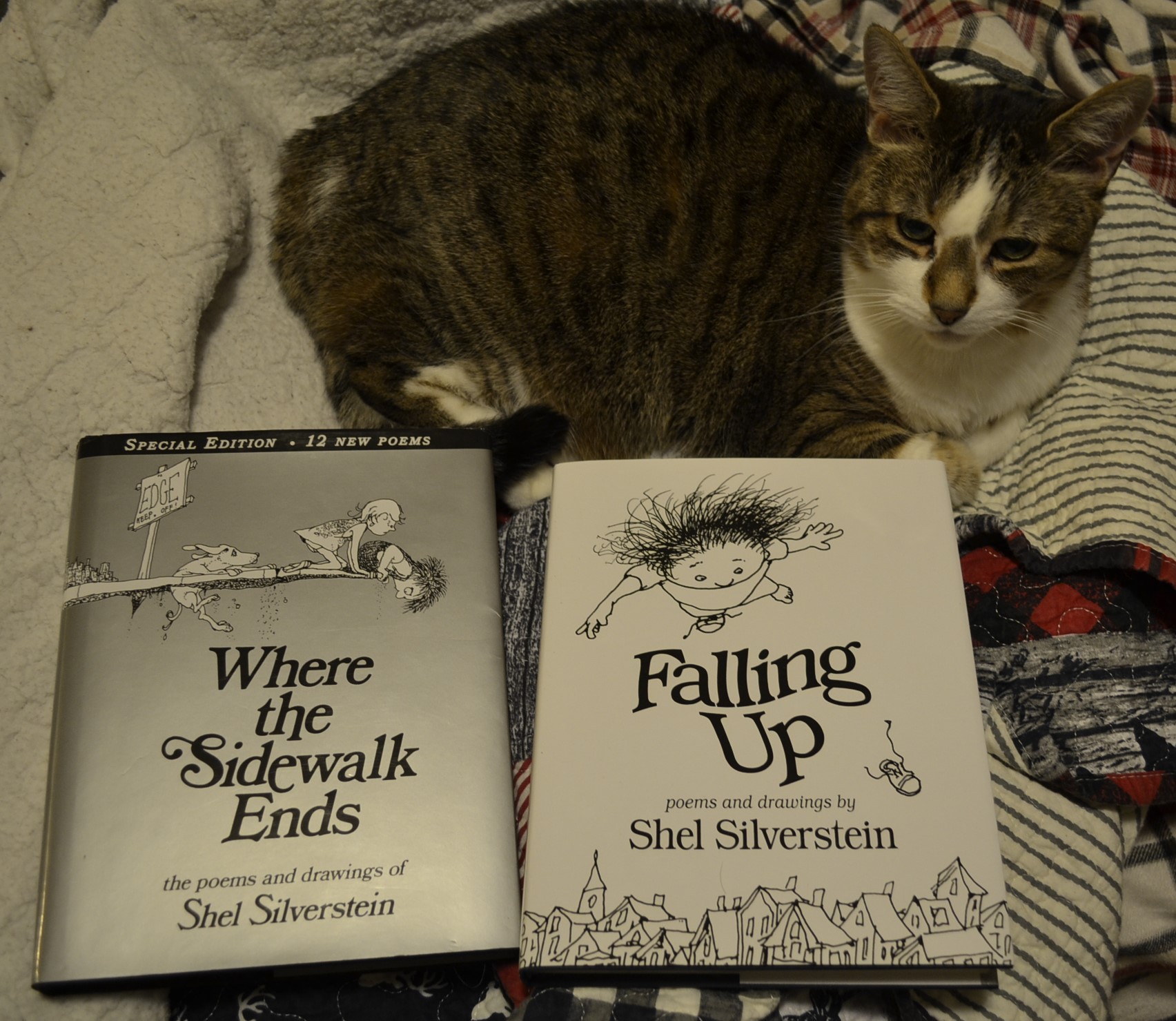

Where the Sidewalk Ends & Falling Up

There’s something very comforting to me about children’s books that rhyme. I grew up with Dr Suess and Mother Goose and I was read to before bed every night. It was rhyming stories that rocked me to sleep and it was rhyme that I first learned to read before I was formally taught to.