Noir in July

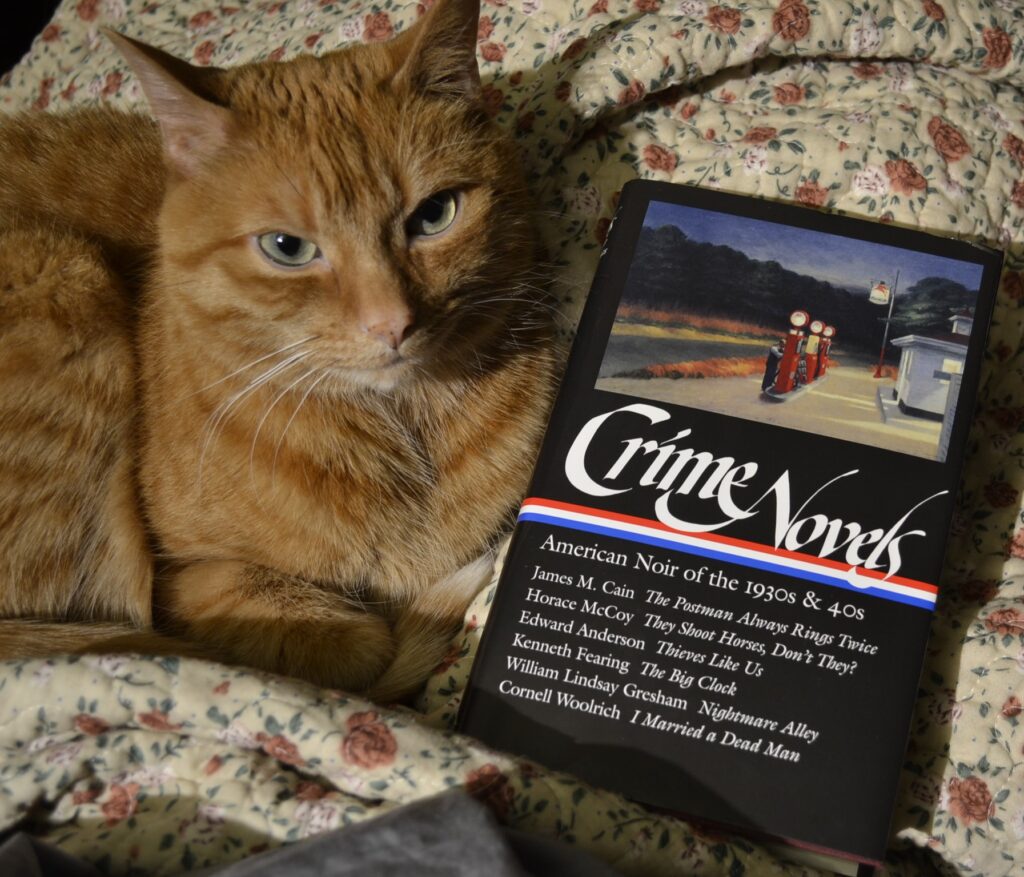

I’ve spent the last three weeks reading a whole lot of noir novels, since my lovely spouse was indulgent enough to gift me with the volumes of them published by Library of America. Each novel was carefully selected and each book is very beautiful with onion skin pages, a ribbon bookmark, gorgeous design, and sturdy binding. These books are meant to look fantastic on the shelf, but also to feel incredible in your hands, and to be a delight visually.

Normally, I tend to avoid single volumes that contain multiple novels, but Library of America has reprinted several lost or hard-to-find classics and has chosen books with the aim to spark more reading and interest in the genre. Like noir? Consider getting these. Love these books? Read more from the writers included here. Opening up one of them is like taking a trip into a well-loved black-and-white film.

For July, I’m going to take a deep dive into American crime noir novels from the 1930s to 1960s, give them a bit of context, and maybe mention a film or two along the way.

Some Context

So, what is noir?

That is not an easy question to answer, and academics don’t necessarily agree — and neither do noiristas. But I’m going to attempt to give a rough definition here. Noir is a genre of literature defined by its devotion to dark subject matter — usually violence. It can focus on a victim or on a perpetrator or it can follow a crime or the procedure of solving it. While it is not synonymous with hard-boiled detective fiction, it does often feature detectives, amateurs or otherwise. It is also not synonymous with film noir. Both share common content and foci, but film noir is also about a specific style of cinematography.

Noir in its essence is about the underside of a world that appears to be in order. It explores violence and crime, not just at the individual level but also systemic violence, corruption, and the shortcomings of a society that allows so many to fall through the cracks.

In the 1930s and 1940s, noir took its focus on the aftermath of the rise of organized crime and the idea of suburbia that would become more prevalent in the 1950s. It examines and reacts to the disillusionment of a generation that has been through one world war, anticipated, and then went through a second. It’s a question of where the American dream was headed, and if it was ever truly real.

The Novels

The Postman Always Rings Twice

The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M Cain was published in 1934 and is the classic story of murder gone wrong and murderers that ultimately cannot live with what they’ve done or each other. This was made into a fantastic film starring Lana Turner and John Garfield which was released in 1946. The book is rather different, and it is a lot more brutal. It is not for the faint of heart, but Cain’s style cannot be imitated, nor easily forgotten.

They Shoot Horses Don’t They?

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? is Horace McCoy’s compact masterpiece from 1935, that was also later made into a film in the late sixties (though I haven’t seen it yet!). It’s a complex tale of a murder done at the victim’s request, all with the backdrop of the strange world of marathon dance competitions. This is by far my favourite of the collection, and was written beautifully as well as being a dark exploration of mental health and its lack of treatment, social responsibility, and performance versus the gritty reality under the surface.

Thieves Like Us

Thieves Like Us was written by Edward Anderson and published in 1937. Its plot follows a group of bank robbers and escaped convicts who are all looking for a big score and a better life. The novel partially delves into the reality of the career criminal attempting to stay constantly a few steps ahead of law, but it also is a statement about the corrupt systems and lack of education that fails those that need them the most to escape bad circumstances, systemic racism, and poverty. It’s not the fastest read, but it is interesting to see just how many times Anderson manages to use the phrase ‘thieves like us’ in one short book.

The Big Clock

Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock was published in 1946, and its claim to fame is its examination of the new and burgeoning magazine publishing industry of the mid 1940s. It features an outlandish structure with multiple viewpoints that increasingly overlap. Fearing, unfortunately, does not have the skill to differentiate the voices as much as they needed to be, and I found that more than once I forgot whose head I was in — despite being reminded at the beginning of each chapter. Honestly, this novel was quite boring and the protagonist was innocent of the crime but so detestable that I wanted him to be punished anyway. Not a pleasant read.

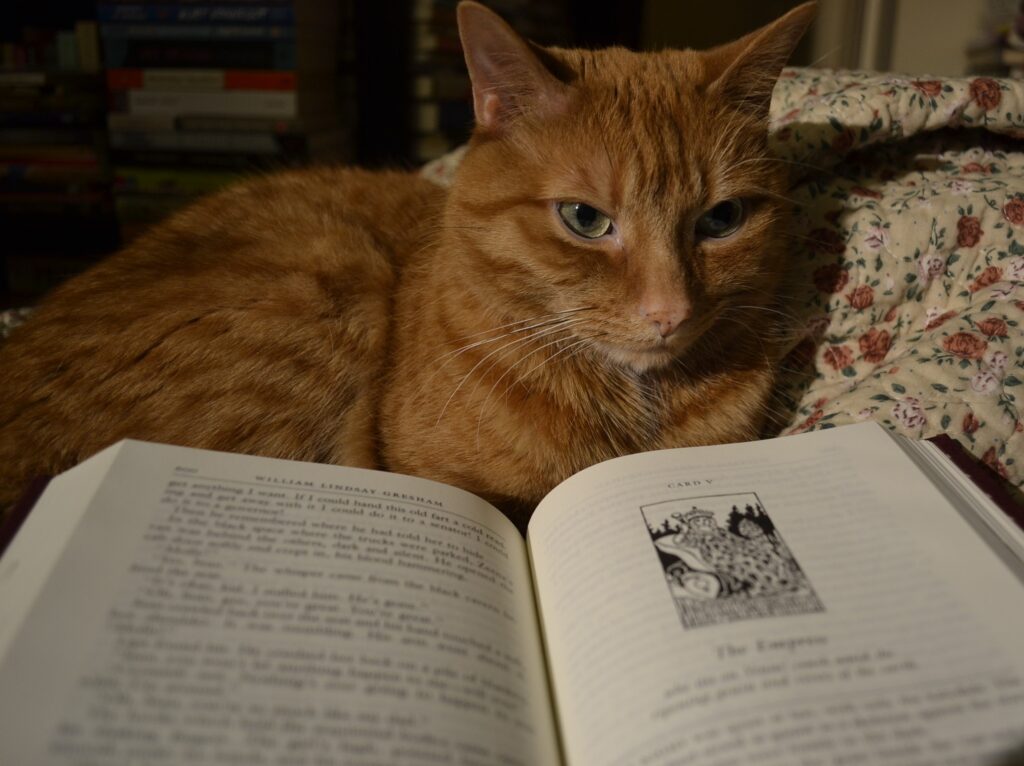

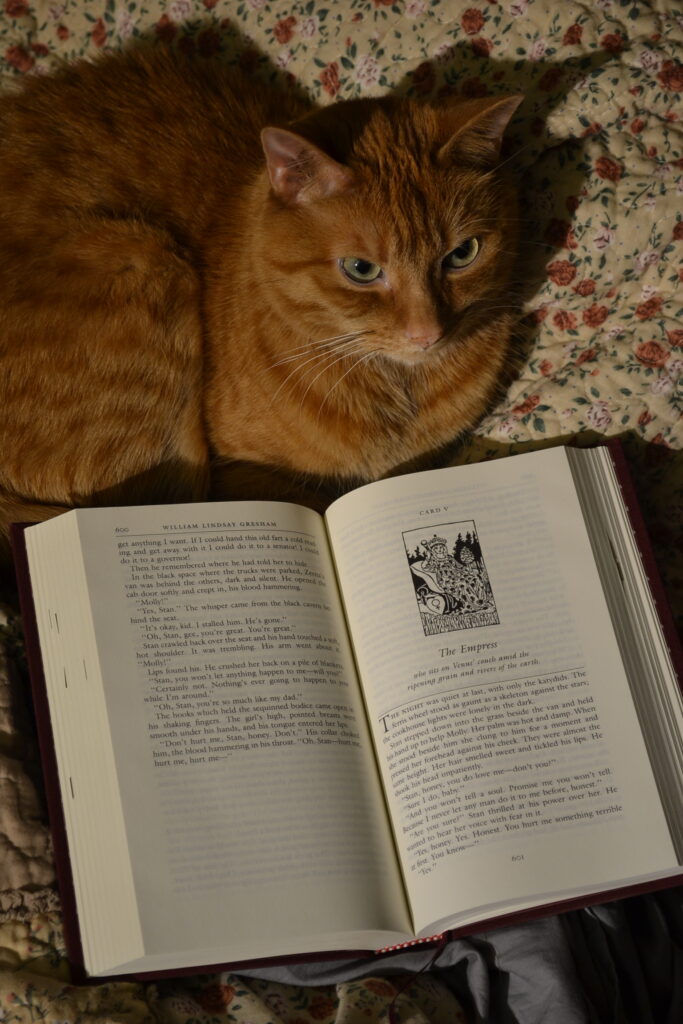

Nightmare Alley

William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley was published in 1946, and I’ve actually already reviewed it on this very blog! As a refresher, it the story of a con man that graduates from working the circus to fleecing the wealthy via spiritualism. A great read, and a great film starring Tyrone Power from 1947. Please ignore the film ending, though. The film’s ending was written by the censors and it is truly awful compared to the Gresham’s.

I Married a Dead Man

I Married a Dead Man by Cornell Woolrich was published in 1948 and, while it is full of twists (including a train accident and a case of mistaken identity that keeps getting more and more complicated), I ended up not caring much for it. Too many of the twists were predictable and the protagonist was both pathetic and annoyingly empty-headed. I would read more of his work, but not ones that feature female main characters. He had a hard time characterizing women in a way that makes them more than flat stereotypes. However, he isn’t stellar at male characters either. There were also some definitely some cringe moments.

Next Week

Next week I’ll be taking a look at the volume collecting American noir novels of the 1950s, which includes more than one very famous title.

Hopefully, I can get the cats to sit still in some dramatic lighting. But they don’t tend to prefer the shadows — at least when I’m trying to get them to sit in them. Usually, that’s the exact moment they cannot be found anywhere in the house.

Maybe I need to somehow locate a cat-sized fedora? I’ll come up with something.