Take Your Kid to Work Day

My mother works in healthcare and has for decades. Now, she has stable hours and no longer has to work odd shifts, but when I was a kid she had to. There were times when she wouldn’t be home until after midnight. Days that were broken by phone calls summoning her back in to work. Sometimes she’d have to take me with her into the basement of the hospital, to the imaging department, and give me busy work to do in one of the offices while she worked. I remember the blue glow of light boxes casting shadows on the pages of my activity books, reels of stickers that were given to pediatric patients, and the rustle and clatter of film in the old x-ray machines.

In a lot of ways, the hospital seemed like another world. When I got older and studied health psychology as part of my degree, I realized that’s exactly what it is. Another world with a culture, language, and feel that are all its own. One that can be scary or at the very least intimidating as doctors, patients, families, technicians, and other staff share the goal of treatment and recovery.

The Meaning of Perseverance

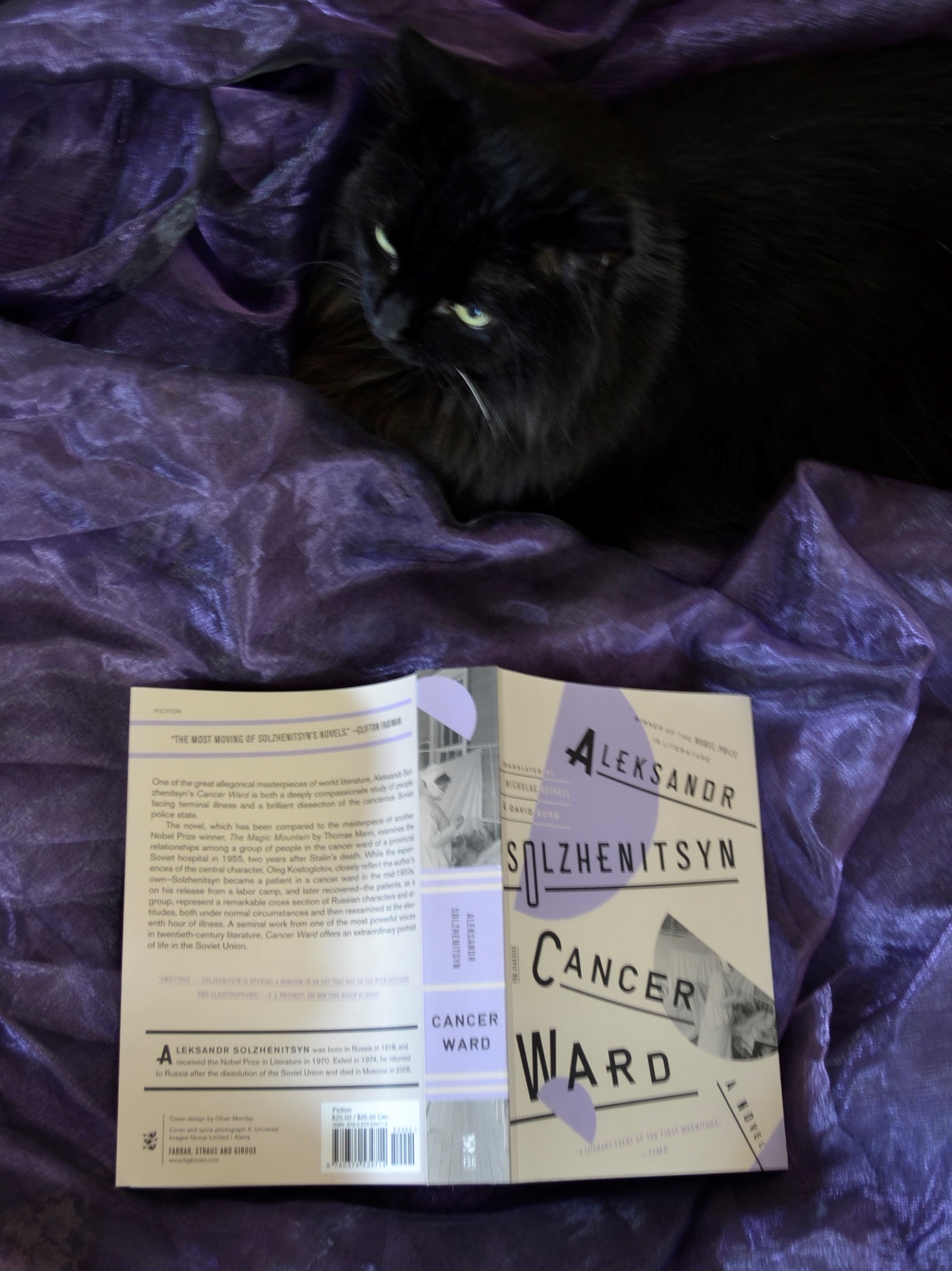

Before I begin reviewing Cancer Ward, I think something should be said about Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and his incredible perseverance. He is one of my favourite authors, not just because of his skill as a writer, but because of how dedicated he was to writing. He was imprisoned. He was the continual victim of a state that was actively trying to suppress his work. His manuscripts were destroyed. Attempts were made on his life. He was sent disturbing images of car accidents to try to psychologically torture him.

Solzhenitsyn kept writing. He had something to say and he said it. He kept going. When I think of what he went through, I think about the power of words, and even on the worse days, I keep writing. I keep reading.

I keep going.

In the Ward

Cancer Ward (Раковый корпус) is the story of several doctors, nurses, staff, and patients in a cancer ward at a provincial Soviet hospital in 1955, two years after the death of Joseph Stalin. As the patients deal with their illness and treatment, Solzhenitsyn takes the reader on an in-depth study of the different reactions to a cancer diagnosis, death, and hospital life.

He asks the reader to consider complex questions of life and death and decisions concerning quality of life. The patients struggle not just with death, but with what life means after an experience of health crisis. The doctors struggle with not just the death of patients, but with the realities of treatment and with the limitations of medicine.

Cancer as Metaphor

Solzhenitsyn skillfully uses the illness of the patients and their reactions to illness as well as life in the hospital in general to make a scathing critique of life in the Soviet Union. He uses the damage of disease to make a statement about what Stalin has done to Russia and the Russian people and what the state turned into after his death.

The characters he writes are representations of different attitudes present in Russian society at the time. There is a patient that is a corrupt government official that is blind to his own illness and blind to anything outside of his role as an official and what the state tells him. He reacts based on fear, anger, and regulations. Another patient is an exile that questions if he wants treatment or if he wants only to go back to his place of exile and accept a death that will come sooner rather than later. He also contemplates how his exile has changed who he is and the damage it has done. Another patient wants to leave a mark on the scientific community before he dies so he won’t be forgotten. Still another thinks about what the rest of his life will be like without one of his legs.

How these patients deal with their cancer is meant to represent their relationship to the Stalinist regime, the government, and what the government has done to the country and society. Some are blind to what has happened due to youth or willful ignorance. Others cannot think about anything but their illness and their fear and how they can keep going. They wonder what life is now and what it will be like and they think about what they have suffered and the suffering of others. They realize that there are shattered lives that will never be the same again. They wonder at what they have become.

It’s not an easy thing to write effectively, but Solzhenitsyn manages to do so beautifully. Effortlessly, he weaves in layers of concept, meaning, and metaphor that is incredibly complex but at the same time poetic and accessible.

Sickness

Solzhenitsyn’s insight on illness and the psychological impact of it in patients is remarkable and is what makes Cancer Ward stands out as a modern masterpiece, in my opinion. Raw and emotional, Solzhenitsyn presents a portrait of the sick and the dying that has an undeniable authenticity. He does the same with the doctors and staff that are trying to save them.

Cancer Ward takes pains to describe the realities of treatment at this point in history. It’s quite terrifying to see how radiation was used and the lack of precautions in x-ray facilities. The descriptions of the feeling of radiation in the air was particularly frightening. Also, the lack of knowledge that patients had about their treatment and prognosis was disturbing. Several are sent home with false hopes that they would return for more treatment when actually they were expected to die soon. Others aren’t told about what injection they’re receiving or what side effects to expect.

Too Short? Too Long?

Cancer Ward is five hundred and thirty-six pages and I don’t think that it could be shorter. Solzhenitsyn’s work tends to be on the longer side, but it never feels like it’s a long book because of how he uses the word count and the skillful way he connects multiple plots, characters, and details. He is continually presenting a new facet, a new comment, a new critique or statement that keeps the narrative fresh and pushing it further.

It takes time to read a Solzhenitsyn, but that time is well worthwhile. Even after you’re done reading Cancer Ward, you’ll be thinking about it and about everything that was in it. That phenomenon doesn’t happen to me often, but it does with Solzhenitsyn’s work.

Remnants

I’ll always remember the hospital and the hospital basement as one of the settings of my childhood. I spent a lot of time there and listening to my mother’s stories of what it’s like to work in healthcare. It always makes me grateful for my own health and the health of my lovely spouse. I try to savour every second I can and feel the happiness that comes just with being alive.

In times like these, healthcare and those that work in healthcare and essential services are so important to keep everyone safe.

So, thank you, healthcare workers.

Thank you, essential workers.

Thank you, everyone that is working to make the world keep turning and to make it healthy and safe as it does so.