Endings

December was busy. Far, far busier than even the holiday season had a right to be and more disturbingly, there was the feeling of endings in the air. We’d finished renovating our basement disaster a month ago, but now it felt like it was actually over and we had to deal with all the things that renovation had pulled out of the moldering walls. Namely how worn thin we were from work and how worried we were about money.

It really hadn’t been a good year and my favourite antiquarian bookstore was closing. Full of built-in shelves and rare books, even the air in that store was amazing. The scent of cared-for old paper and editions that were bound with consideration wrapped around you when you crossed the threshold and didn’t let you go until you had found at least five things that you weren’t even aware you were looking for.

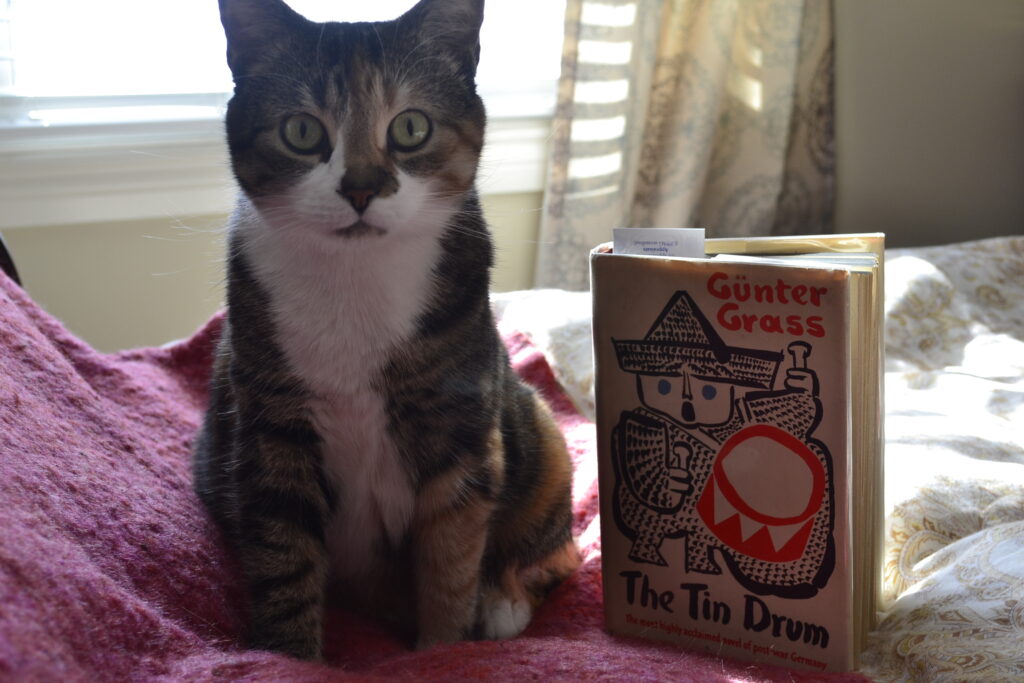

It was on our last trip there that the bookseller placed Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum into my hands. For the last few months I’d primarily been reading Russian literature, but in the final hour all bets were off and my very generous spouse wasn’t letting me say no to any kind of literature in translation. So we left the store with at least thirty books, including this one.

The Absolute Basics

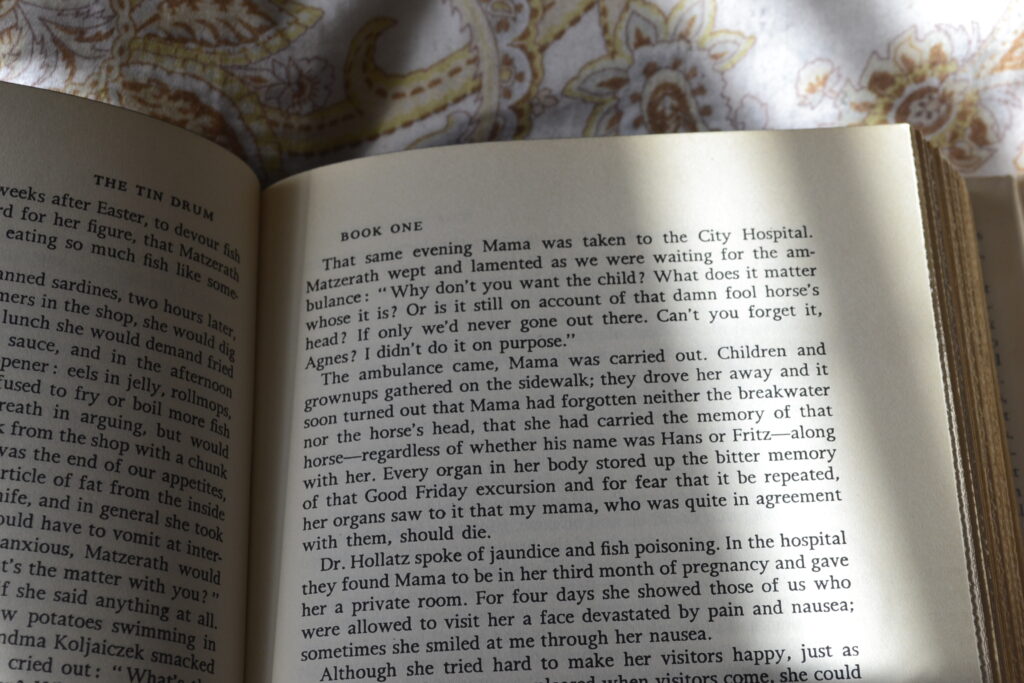

This book is the fictional autobiography of 30-year-old Oskar Matzerath, beginning with his birth, his childhood, and his fixation on a tin drum given to him on his third birthday and ending with his commitment to a mental asylum. The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel) is considered an essential of both German and general postwar literature.

The Cover and the Old Paper

The Tin Drum actually didn’t spend as much time in my stacks as some of the books I get do. There was something about the plastic-wrapped, slowly yellowing cover that drew me to read it as soon as possible. Grass’ picture of a blue-eyed boy drawn with harsh bold lines, holding a red and white drum screamed out from the page with a style that is at home in posters pasted on telephone poles. It calls to mind both a child’s near abstraction in their first drawings as well as having a certain starkness to it perfectly appropriate to a work that is at the same time rife with details and devoid of them in places. The image itself is a self-portrait that only gives a few details of the subject. It is also unreliable, just like the narrator.

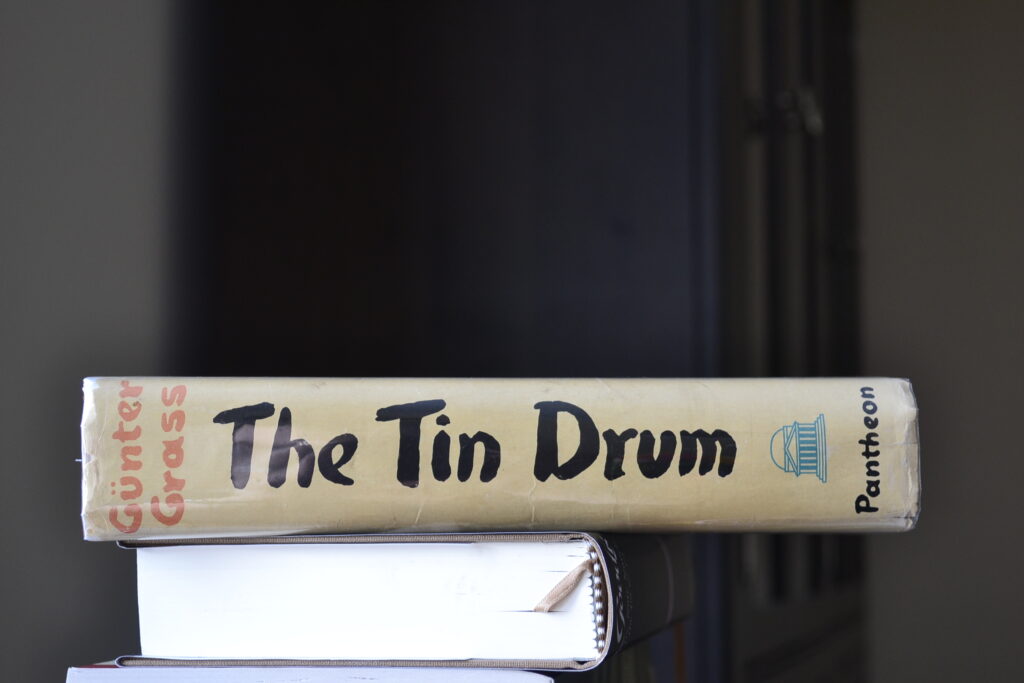

The first American edition is the one I have, published in 1962 by Pantheon, with the smell of old paper that specifically reminds me of going through my grandparents’ paperbacks at their cottage. The cover is wrapped in plastic like an old library book. The size is squat. It fits in the hands and is comfortable, just like the size and spacing of the type. It needs to be comfortable, since you’ll be reading this nearly six-hundred-page narrative for quite some time.

Interestingly, I saw a copy of The Tin Drum identical to mine in the background of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? when we watched the movie on TCM a few weeks ago. It sat on a shelf behind a bed with the distinctive lettering on the spine starkly sticking out amongst the books around it.

To Beat a Tin Drum

Wikipedia describes the genre of this book as ‘magical realism’.

‘Magical realism’ are not the two words I would use to classify The Tin Drum. Are there elements of that genre in the book? Well, yes. Oskar Matzerath describes his own birth, shatters glass with his voice, and uses his drum to make people behave in strange ways at times. But would I recommend this book to someone that enjoys the magical realism genre? No, I would not.

Why? The elements of magical realism are not meant to be very magical. They’re meant more as a way to illustrate a vital thread of the novel — the unreliable narrator.

It’s a popular device that is rarely used well — or even correctly — but here Grass shows a great deal of skill in the way he layers the murkiness between Oskar’s inner world and reality. Oskar describes an event that seems to have happened, but then drifts off into describing things that couldn’t have happened or else his own delusions and symbols. His knowledge is too extensive but also steeped in ignorance at the same time. He sees himself as in control of events that clearly are out of his control. In this constant confusion, Grass draws the reader into the chaos of the population of post-war Germany. And, interestingly, he decides to use objects as touchstones — the most obvious being the drum itself. Oskar uses drumming to literally conjure his memories and uses the acquirement of drums as a marker of time. The drums are real, but the memories are again subject to the delusions of the narrator. One gets the sense that the history is only objective in terms of these objects, highlighting the subjectivity of memory and storytelling in general.

But what is the tin drum? As a symbol, it’s a manifestation of pain, futility, and horror at the complacency Oskar sees all around him. Oskar beats the drum in the psychological climaxes of the book and at the moments of the novel’s twists and turns. The noise of the drum constantly hammers in the background when something is happening that Oskar cannot control and goes on to reshape in his own mind. Matzerath, Jan Bronski, Agnes, Maria — almost every character displays a willing blindness in spite of the horror they experience and the horror around them, and in spite of the beating drum.

Grass is trying to say something that is profound yet ugly at the same time. Grass weaves a story full of deception, illusions, and outright lies that is not for the faint of the heart. He speaks to how, no matter what horrible things happen, some individuals will always remain willfully blind and willfully ready to forget that anything happened and will go back to their mistaken idea of normalcy no matter how broken it may be. How far some will go to keep up the illusion of power and control.

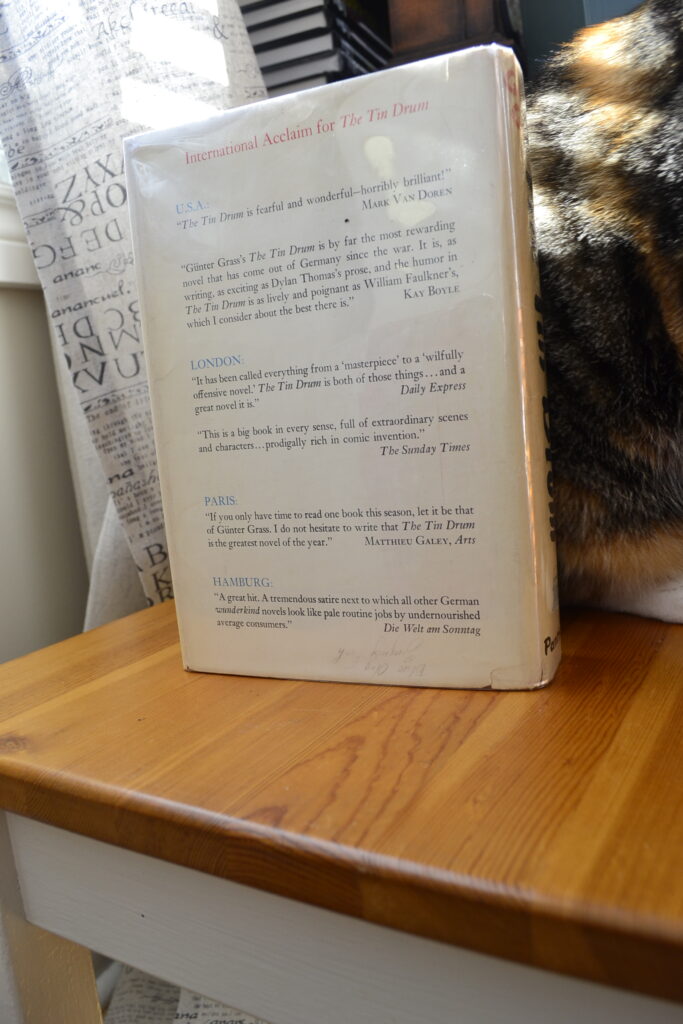

Mixed Reviews from Other Sources

The back of the book is a list of reviews that are quite contradictory. And doing a bit of research, I discovered that reception and criticism of The Tin Drum was quite mixed when it was originally published in English. Some called the book willfully obscene. Others called it a masterpiece from the start.

As for myself, I don’t agree that the book is obscene; though there are disturbing scenes that are described with detail, it’s not gratuitous nor meant to shock. Grass uses the grotesque to point out something ugly, not to wallow in his own grotesqueness. That being said, I can see the imagery being too much for some readers, so do be aware of that before you start reading.

Parting Thoughts

Despite being a difficult book in many ways, some of which involve graphic content and some very intricate and sometimes hard to interpret technique, Grass has written a work that deserves its acclaim. It is worth the read if only for the example of unreliable narration used skillfully and to maximal effect.

However, The Tin Drum requires patience and a willingness to do some research into the context it was written in as well in regard to a few of the specific historical events mentioned in it. Again, the reward is worth the patience required. I learned a lot about structure and metaphor from reading Grass’ unique writing and use of literary devices.

New Beginnings

Though I bought this book without so much as checking the summary, it has convinced me to read more German works in translation and more Günter Grass. Like when I start reading any new area of literature, I’m excited to see where it leads me.

I’m still sad that the bookstore is closing, but I’m grateful for the year I had of their phenomenal stock and gathering a lot of rare literature in translation. I’m also grateful for the many, many stacks of books I have from that shop to get me through the cold months ahead. True, I have to get them under control because my wife just stubbed her toe badly on the edge of the stack in the hallway, but I never dislike organizing old books.

If only the cats would stop insisting on climbing them like mountain goats.