Mobbed by Chickadees

It’s cold and that means it’s the season of the chickadees at our local trail. Bring them seed and they will honour you by landing on your hand one after the other. However, with the few days of extreme cold, there probably haven’t been as many hikers willing to brave the temperatures. So when we went out to feed them yesterday, we basically got mobbed by the cute little cheeping things. I had some of them on my sleeves A few landed on my toque. There were so. Many. Chickadees. It almost made breakfast time with five cats (including specialty diets) seem calm.

Customs and Culture

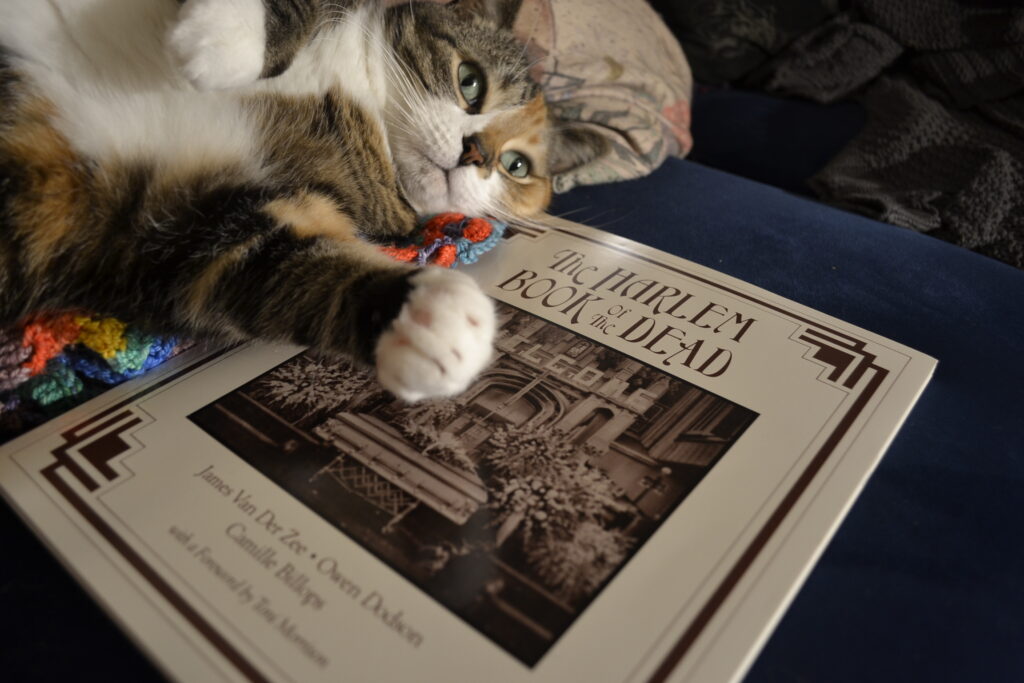

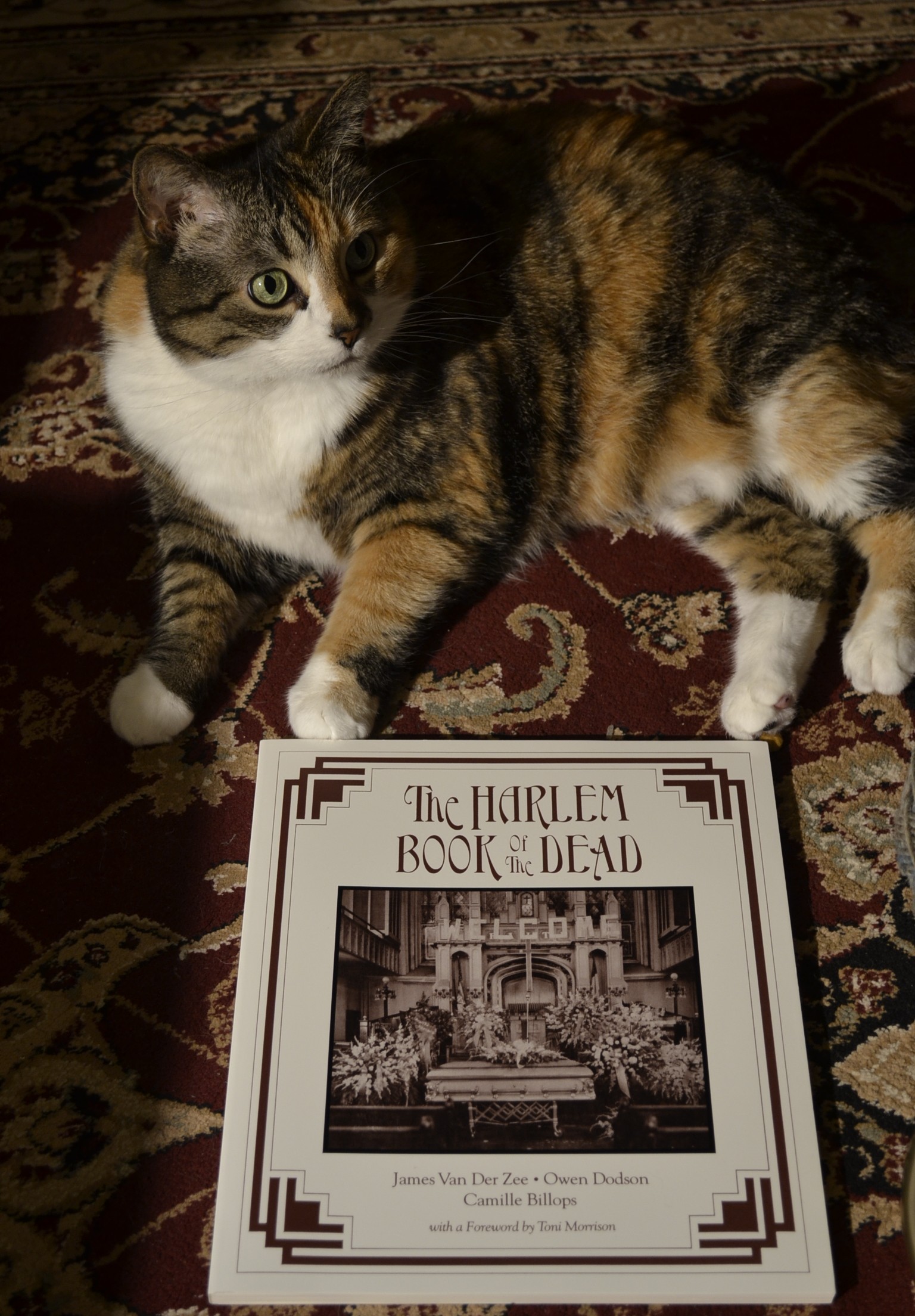

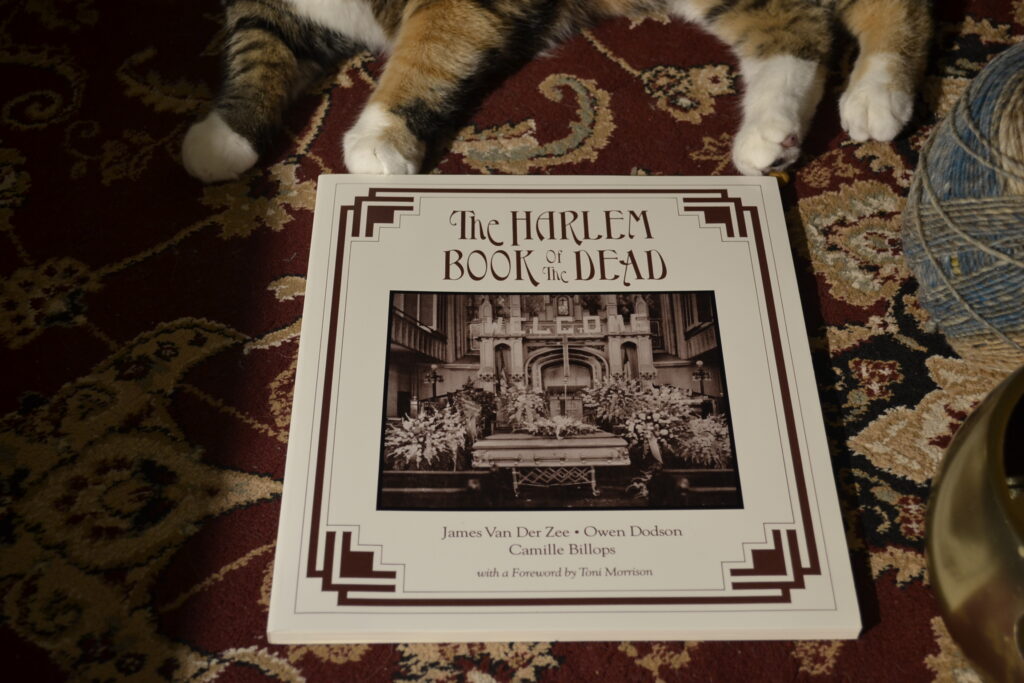

I’m a bit late to the Black History Month party, but that is what I get when I try to write reviews early and lose track of which week is in which month. However, I have decided to kick off a celebration of Black literature on the blog with a book that has recently come back into print — The Harlem Book of the Dead with photographs by James Van Der Zee, poetry by Owen Dodson, and an interview conducted by Camille Billops, who also organized the volume in general.

Every culture and region has a variation on funerary rites and customs associated with the dead and saying goodbye to their loved ones. Harlem in the 1920s through 1960s was no different. The Harlem Book of the Dead is a sampling of the work of James Van Der Zee, who was both a conventional as well as a funerary photographer, paired with the mourning laments of Dodson’s poetry. It’s a beautiful testament to the love and care that went into caring for the dead, as well as the images that survivors carried with them after the funeral was done.

The Power of the Photograph

These photographs aren’t easy to look at, especially the ones that show deceased children. But despite the death present and heavy in the frame, the love and devotion is still there. A father holds his baby. Two parents hold theirs. A child grips a teddy bear in a crib. These are the last moments at home before the body is taken away and passes forever out of their touch and care. I found these to be the most moving of the included work because it captures a moment of goodbye.

All of the photographs are so carefully done complete with overlays and touch-ups that made Van Der Zee a master of his craft. More than a memento, these photographs are meant to comfort as long as they are kept close to the mourning.

Process

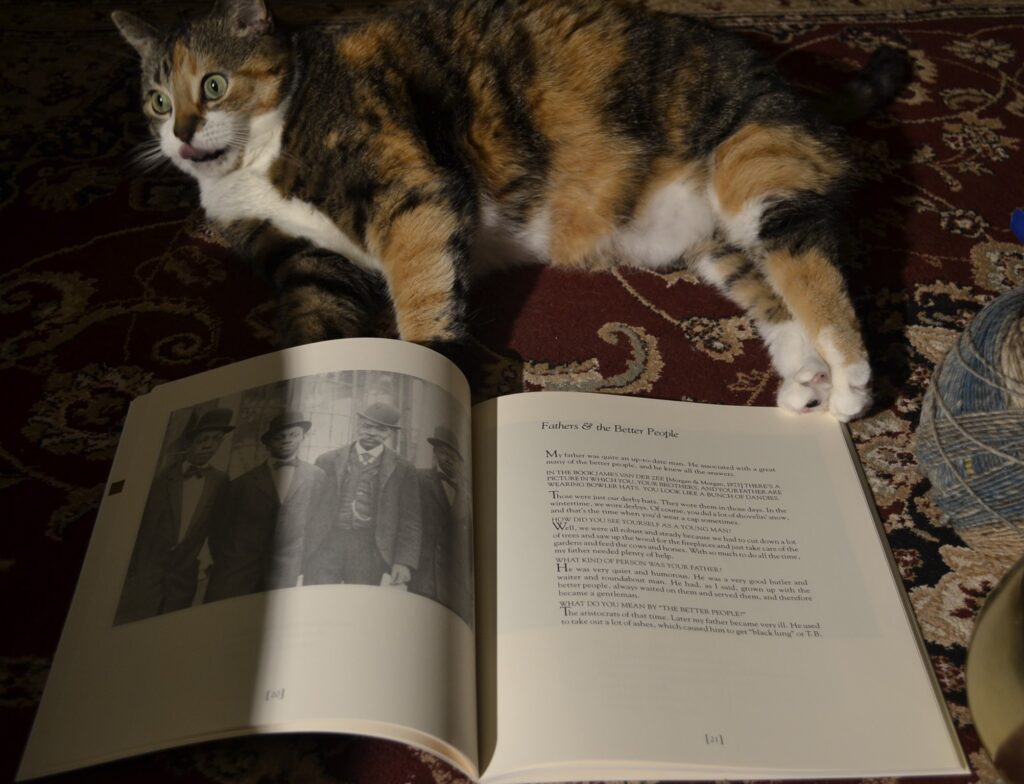

While Billops’ interview with Van Der Zee is interesting and sought to place this work in the context of Van Der Zee’s studio and the time in which he operated. I found that I really wanted to hear less about Van Der Zee’s personal life and more about his process for each photo or at least a general procedure that he followed to produce his work. Mostly in this interview Van Der Zee talks about his relationship with his wives, and while that is part of the picture of who he is, I’m not sure it’s exactly relevant to his photography or photographic practice.

However, I did love that there is an individual description of most of the plates at the back of the book that do provide some of these details and specific memories that Van Der Zee had of these clients.

Bunnies too!

My lovely spouse has a soft spot for bunnies, so she also has been leaving extra seed out for the wild rabbit that has made a home in our backyard. At this point, there is so much snow that the rabbit limits itself to the paths we have shovelled from the porch to the shed to the back gate, and then it squeezes itself into the front yard to leap to its bunny delight in the cleared-off driveway and around the courtyard that has also been cleared as much as possible. At least somebody enjoys the fruits of our shovelling labour. Right now, it feels like all I do is shovel so that I can get out of my driveway and get errands done.