The Longest Drive I’ve Been On

When I was a kid, I hated the car. My family never ceases to come up with stories upon stories upon stories about how I cried at the start of every small road trip and how difficult it was to get me to even go near a car. Part of the reason is that I was often carsick, but the other part of the reason was that I found the time spent on the road so endless.

I got a dose of that old feeling pre-emptively when we started talking about a drive to New York City. Seven hours in car seemed impossible. I was worried that I would get sick or that I would be bored enough to regret every kilometre we drove. But my lovely spouse encouraged me that it would be fun. She was right. Those seven hours flew by in the fall foliage of Pennsylvania and in the conversation we had about just about every subject that crossed our minds even for a fleeting second. It was an adventure that brought us closer as the distance lengthened between us and our hometown.

I look forward to road trips now, mostly because it’s an opportunity to get away from work and to just talk. About everything.

An Ode to Mobility and the Automobile

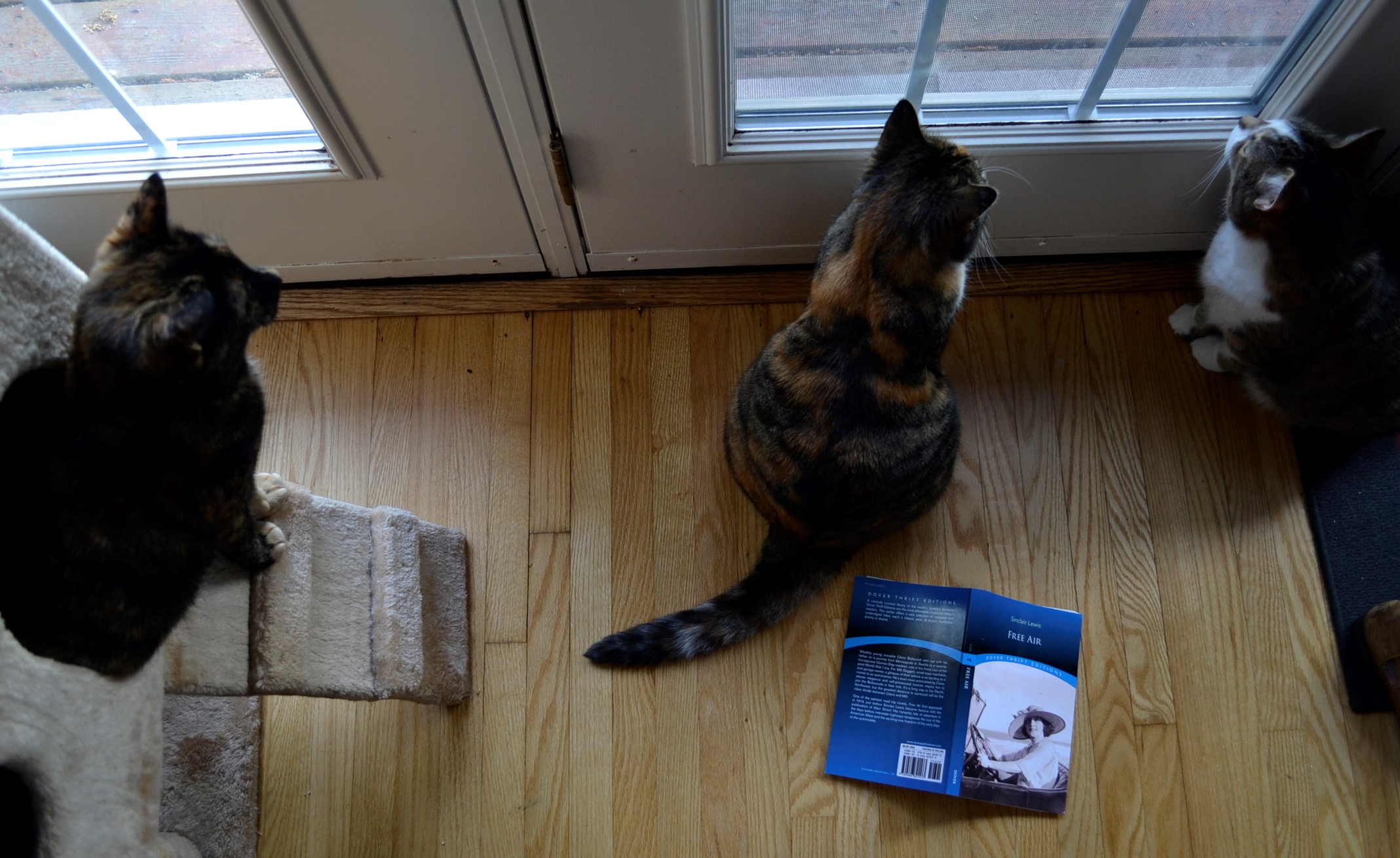

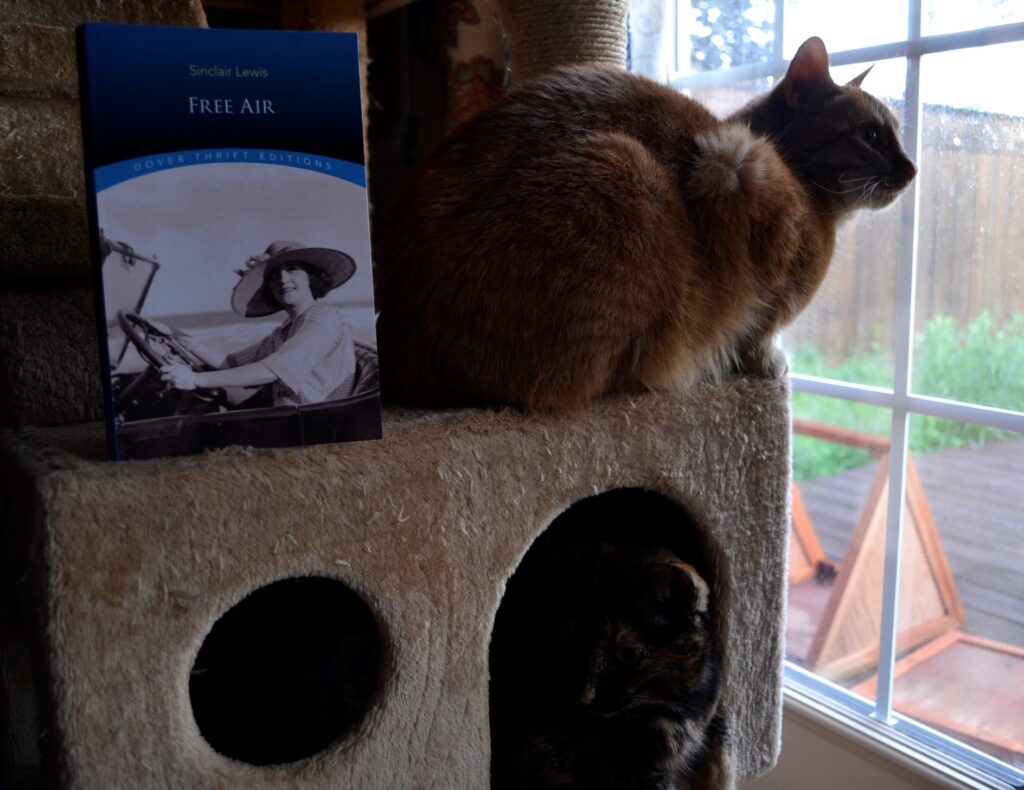

Sinclair Lewis’ Free Air from 1919 is a novel that is also a celebration of the new sense of mobility that the automobile gave to the American population at the turn of the century. Suddenly, you could jump in a car and drive across the country when previously you would have been limited by the reach of the train or else a horse and buggy.

Claire Boltwood is on such a trip across the country — driving herself and her father from Minneapolis to Seattle in a very nice car on some not very nice roads. Lewis describes not just the scenery but also the reality of flat tires, car repairs, getting stuck in mud, and unpleasant hotels. The detailing of the mechanics of running a car when the technology was still relatively new to consumers as well as the newly formed ideas of etiquette on the road has historical value that is worth the read alone for those that love to learn about history through literature.

Of course, the novel isn’t just about the trip. It’s also about the romance between Boltwood and a mechanic named Milt Dagget who is from a world entirely apart from that of the high society of New York or Seattle. The romance forms a comment on the divide between these two characters in terms of class and how they attempt to bridge it by meeting one another on the common grounds of nature and the road.

Two Worlds Collide

As much as Lewis means for the worlds colliding to be that of Boltwood’s and Dagget’s, it at once becomes obvious to the modern reader that the colliding worlds are that of turn-of-the-century writing conventions and modern sensibilities.

The most obvious issue is that on which the plot revolves. Dagget sees Boltwood in a garage, overhears that she is headed for Seattle and then packs everything into his car and follows her. Without meeting her, speaking to her, or knowing the least bit about her. He follows her across hill and dale, and that really doesn’t sit right with a modern audience. It’s harassment. It’s stalking. And that’s what their relationship is basically built on.

It’s disappointing because it really takes the focus off of what the reader should be focusing on. Boltwood’s snobbish attachment to the luxuries of high society and Dagget’s desire to be part of that society and his fear and disgust of it that are each in direct conflict. Dagget wants to better himself and get an education that would take him beyond being a mechanic in a small town garage, but as much as he doesn’t wish to be mired in small town prejudices and closed mindedness, he also doesn’t wish to become part of the frivolous and flippant upper crust.

Boltwood has a similar problem, but Boltwood is struggling with being attached to luxury but not to the prejudices of high society and their scorn for anything that they see as ‘beneath them’. However Boltwood’s struggle is more frustrating to read because it’s described as longing for perfumed baths and also road trips. There’s an air of shallowness attached to Boltwood’s struggle that rapidly puts it in the back seat.

The Problem of Claire Boltwood

Though Free Air begins as being primarily about Boltwood, she starts to fade into the background as Dagget enters the narrative. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because there are a lot of things about Boltwood’s character that are hard to struggle through.

Lewis writes female characters that would have been incredibly complex and unique for the time he was writing them in. Boltwood drives herself across the country. She has thoughts and feelings and emotions and ideas that she isn’t afraid to voice. Lewis definitely intended to write a strong female character.

But, whatever the intention, that isn’t what Boltwood is. Male characters have to help her out of nearly every problem. She protests that women don’t want to be carried off into the sunset, but in the end that is exactly what she wants. She tells Dagget to stop following them, but doesn’t remain consistent to her word. She doesn’t know what she wants. She’s shallow and contradictory and constantly indecisive. She makes promises she keeps breaking. Her major conflict is mostly between two different men, and only tangentially between two different ideas.

In short, she’s a frustrating character because she is supposed to represent one thing but is in fact the opposite. To a modern reader it comes across as hypocrisy and sexist tropes in writing. However, when I struggle with a character like Boltwood, I try to take a step back and put the writing in a historical context. It doesn’t help every time, but it can help get through a book I wouldn’t otherwise finish.

Lady Vere de Vere

I do like Sinclair Lewis’ work, but even great writers sometimes have moments of not-so-greatness. In Free Air, I have to say that I really did not like what happened to Dagget’s cat — Lady Vere de Vere — and her sudden death. It reads like Lewis simply didn’t want to write about the cat any longer. It seems so unnecessary, like the cat should have never been there in the first place rather than the reader being forced to deal with an animal dying in text.

A Brief Word About Boats

Like many other Canadians, I can’t possibly talk about road trips and summer without talking about the nearly weekly trip out to the cottage or about what the lake meant to me and my childhood. Next week I’ll be talking about the drives to the water and the bright yellow paddleboat that was a staple of every weekend.

The literary road trip is going back to 1889 for a review of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat.