Where Christmas Falls

It’s funny, but when it comes to Christmas, the day of the week it falls on is usually left out when it comes to making plans and managing logistics. I guess the reason is that for most of them it really doesn’t matter if the 25th is a Tuesday or a Saturday, but I find that it is the week before Christmas when things suddenly take a turn. More than shopping days, for me it’s about managing the crowds that I know will be packing into the malls of nearby cities and swarming the downtown of this usually sedate town as I look at the countdown calendar and realize that most of those remaining days are weekend days.

Weekend days close to the holidays are seldom unchaotic as everyone tries to pack things around schedules that are too tight and too hectic to squeeze in not one event or gathering more. Concerts clash with errands and clash with visits to far-flung family, and everyone is just trying to get it all done and get the most out of these days of celebration before the January gloom. It’s important to slow down, as I’ve said every year I’ve written about Christmas, but it’s also important to have compassion and be generous with your patience to strangers, family, and yourself. I wish everyone all the best in this last hectic week before the holidays begin. May your preparations go seamlessly and may all of your days have at least a pocket of calm in them.

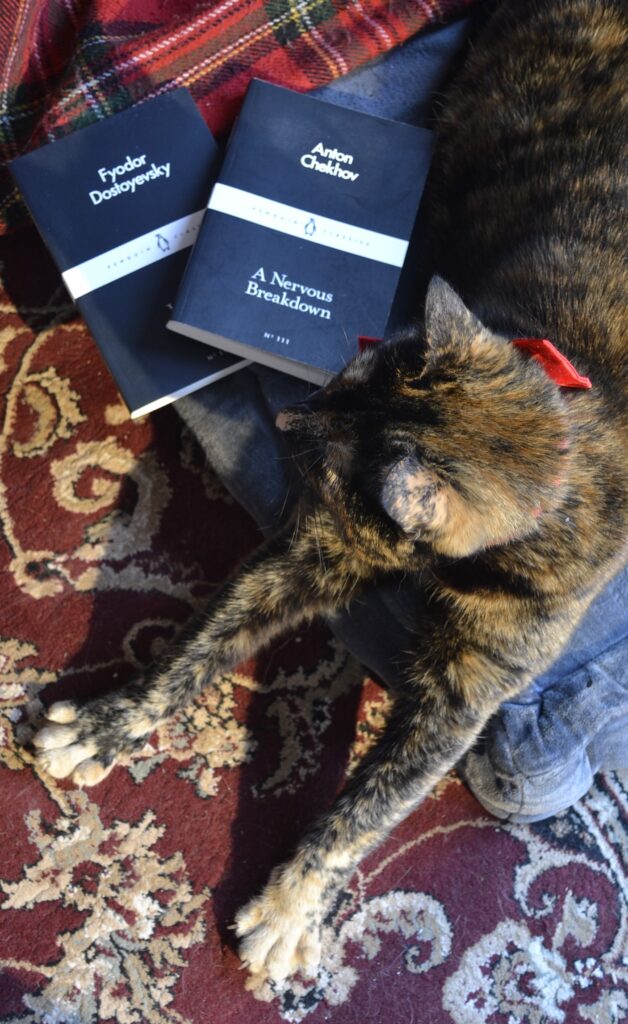

Two Small Books for Cold Winter Nights

I was skeptical at first, but I have grown to really appreciate the collection of Little Black Penguin Classics. They easily fit in a bag and, while they are short, they do not lack for substance. Because it’s the snowy season, I decided that I would review books from a snowy place this week, two Russian classics — Anton Chekhov’s A Nervous Breakdown (a collection of three stories, the titular one, ‘The Black Monk’, and ‘Anna Round the Neck’) and Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s White Nights (a collection of two stories, the titular one, and ‘Bobok’).

Both of these volumes are perfect for a night spent inside in the warmth of the fireside. Easy to get lost in, they are easily finished in a sitting and just begging to be turned over in your head or discussed with your favourite bookish friend. The content of the narratives is a bit closer to the spookier side of things than to the seasonal warmth of the holiday season, but, at least in our house, Halloween and Christmas are siblings, not distant cousins.

Chekhov

I think it’s safe to say that Chekhov is the (mostly) undisputed master of the Russian short story. We even have a writing rule named after him: Chekhov’s Gun. If you don’t know the rule, it’s that if you present information (the ‘gun’) in the first part or act of a piece, it needs to come back (or ‘be fired’) in the last act or conclusion of the narrative.

In the collection of stories, Chekhov takes a deep dive into the internal states of each of his characters and how they clash with those around them — to a darkly comedic effect. In ‘A Nervous Breakdown’, a young man is on his way to a brothel with his friends when, suddenly, he reels at the moral depravity he is descending into. Instead of listening to him, his friends declare him insane as Chekhov comments on just what is considered insane in a moral-less pilgrimage.

In ‘The Black Monk’, a man suffering from hallucinations of an approaching monk marries into a family that runs an orchard. As he struggles with mental illness, he is blamed for the garden’s dissolution as well as the dissolution of his marriage. And lastly, in ‘Anna Round the Neck’, Chekhov examines the pressures on Anna, a young poor woman, to marry and improve the fortunes of her family. When she does so, she gradually realizes that her family used her and that her husband has as well, leaving her adrift, before deciding to fit the mould of a married woman of means.

Dostoyevsky

I found that the Dostoyevsky stories were a little more atmospheric and mysterious than the Chekhov and, though they still contained some bitingly bleak satire, were more stories for the sake of stories with a light sprinkle of social commentary and absurdity thrown in.

In ‘White Nights’, a man who considers himself solitary and friendless is wandering around St Petersburg. He comes across a solitary woman who he saves from an assault, and, over the course of several nights, he talks to her, listens to her story, and shortly falls in love with her — but she does not return his affections. What follows is a story of unrequited affection and the reality of loneliness still being unbroken even when experienced in company. I enjoyed the story in general, but it’s a bit hard to stomach with modern sensibilities as it posits that women have some duty to talk to lonely men, or to give them some kind of consideration. They do not. And that fact alone maims the story’s general premise.

‘Bobok’, meanwhile, is a spooky and humorous tale of a drunk that sees some ghosts of nobility in a graveyard — and they are every bit as petty as they were when they were alive! It’s a nice little tale that serves to cleanse the palate after the heaviness of ‘White Nights’.

Trains in the Dark

We just came back from visiting family and it was a rough train trip home. The train was delayed (though for good reason, nothing to complain about there) which made the entire voyage one taken in the dark of the winter night. But in that dark, I got to watch the Christmas lights go by as various rural communities passed by the window. The quiet in the car was deep and unbroken by anything save the station announcements. It seemed outside of time and space and that is a rare experience during the holiday season.