Spicy Soup on a Hot Day

My lovely spouse always is trying to make me feel special and one of the ways she does so is by making me spicy food. She doesn’t really like spice. In fact, most of the time when we eat anything spicy, she has a glass of milk at the ready. But today she decided that she was going to make me some Szechuan hot pot — even though it’s July and we went on a hike earlier.

Why? Because, the last time we made it, we put in way too much of the flavouring packages and it upset both of our stomachs and therefore she is determined to get the recipe right. And every time she takes a bite and then goes diving for her glass of milk I am touched. I also remind her that it’s okay to just delete this one from our recipe file and opt for something milder. But she has a lot of determination and that is one of the things that I absolutely love about her.

The Context

As the 1960s began to fade into the 1970s, noir took a fascinating and complex turn. It wasn’t enough to just be about a crime — now it was about being relevant to the current moment. Simple escapism was left behind so that storylines could examine themes that went outside of the box and into social commentary. From systemic racism to the early days of the opioid crisis and then to colonialism and the American presence on foreign shores, complex characters with complex issues and plots surfaced. More than just a lot of moral grey areas, noir began to delve in different shades of grey, and the aftermath of crimes that escaped the confines of the letter of the law and crimes that were showing evidence of becoming widespread, global problems.

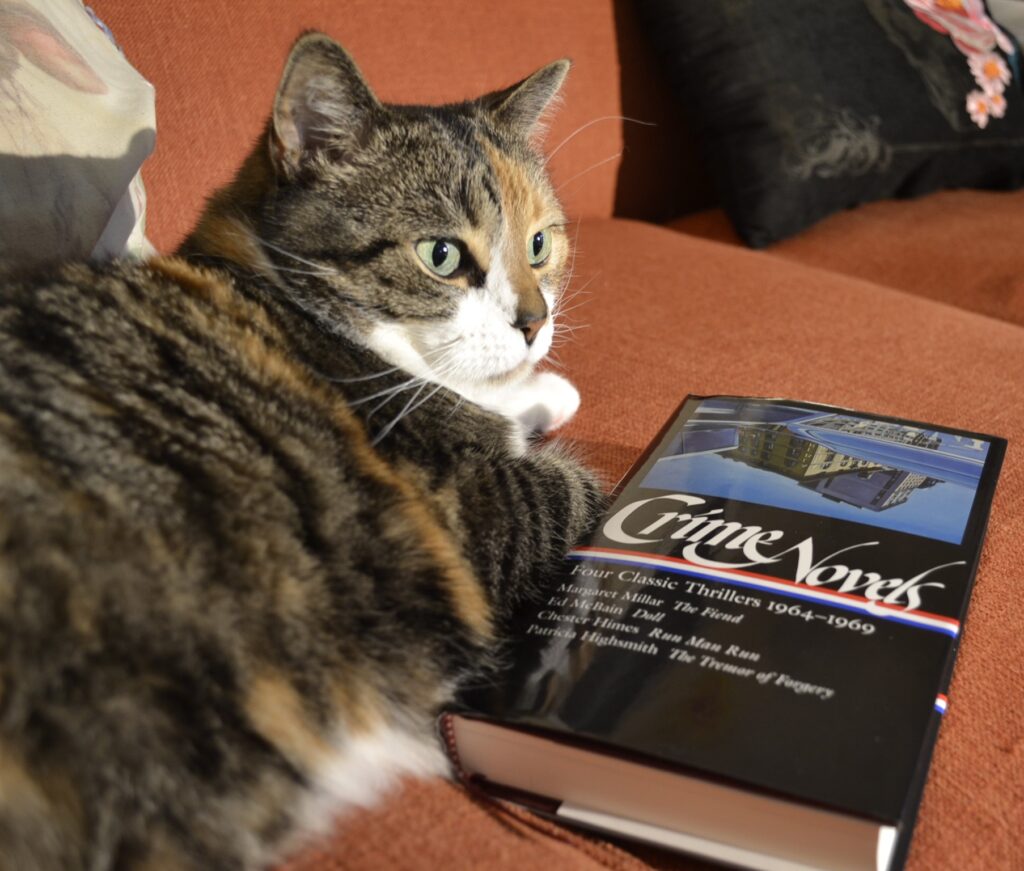

The Novels

The Fiend

In Margaret Millar’s The Fiend from 1964, the reader is taken on a deep dive into suburbia and the pettiness and jealousies that can lurk below the surface of a seemingly strict compliance to decorum and normativity. Millar’s writing is technically good, and the twists and turns she throws into the plot will keep you turning the page. However, times have changed and it’s hard to read a narrative where a child is blamed for ‘leading on’ and ‘inciting’ the behaviour of a mentally ill man. A child cannot consent and there is nothing a child can do that would in any way justify an adult’s deviant behaviour: it’s just victim-blaming. And, equally painful, it’s not believable — in the sense that there’s a false accusation plotline that just does not ring like it could ever be true. Also? There’s a hint of misogyny in the final twist. It wasn’t my favourite of the collection — even if it did read exceptionally well on a sentence level.

The Doll

Ed McBain’s The Doll was published in 1965, and delightfully, Library of America has included the images and illustrations that would have accompanied the first edition. A model has been murdered and what follows is a trip down a drug-fueled rabbit hole that involves a kidnapping, a doll, and an abandoned house. Mostly the star of the narrative is the homicide division of the 87th precinct, which is a focus of many Ed McBain novels. So, if you liked this book, there are plenty more for you to seek out. I will warn that there is sexual violence in this narrative.

Run Man Run

Run Man Run was written by Chester Himes and published in 1966, and unlike the Chester Himes book included in the 1950s collection (The Real Cool Killers from 1959), it is a standalone story focussed on systemic racism within the NYPD and what happens when a young Black man identifies a NYPD detective as his attempted murderer. Small spoiler? No one believes him, which leaves the murderer free to try to finish the job as a tense chase unfolds across the indifferent city. One thing I will note, the character of Linda Lou (the protagonist’s girlfriend) is a very disgustingly written character that is very hard to read. Also, there is a lot of sexual violence, and a flippant treatment of domestic violence.

Tremor of Forgery

Patricia Highsmith’s novel Tremor of Forgery was published in 1969, and I struggle to label this one a noir novel. Mostly it’s a literary novel in a very thin disguise. The plot revolves around an American that is currently living in Tunisia, where he may or may not have killed a man. There’s a lot of racism and colonialist ideas bandied about, but the bulk of the wordcount is spent on a philosophical discussion of what makes for cultural exchange and what makes for propaganda and whether or not morality is dependent on one’s place of birth. The novel took a long time to get going, and even then it never truly seemed to get anywhere. Not one of Highsmith’s best.

An Additional Note

As you may have noticed, this week’s review included a lot of warnings about sexual violence, misogyny, racism, etc. Part of the trend of the late 1960s version of noir involved pushing the envelope as these writers attempted to hold up a mirror to the society they were living in. The reflection wasn’t pretty and wasn’t meant to be. Unfortunately, these writers were holding warped mirrors, very much shaped by their own prejudices that were not yet recognized for what they were. It can be hard for a modern reader to get through an older genre work for this reason.

There’s a lot of to be learned from these novels, but just like with literature, it’s important to look at context and the era it was produced in.

Tummy Aches All Around

The last time we had hot pot? There were tummy aches, and my lovely spouse had to bow out of the leftovers. This time? My tummy doesn’t quite know what to make of the spice, but it is satisfied and there will be no rush to the bathroom.

Oddly enough, my lovely spouse seems to have completely digested it with the help of only a twenty-minute nap.