Purchasing by Edition

When I purchase books, I usually do a lot of research first. Either I’ve heard of a book from another book I liked, or I have gotten a recommendation from a literary magazine or I’ve seen it arrive at my local independent bookstore’s literary section and then researched it via the internet. I put a lot of thought into what I buy and what I read because I only have so much of a budget and only so much time. I can’t read everything that looks interesting, and I can’t buy every book whose design I’m drawn to.

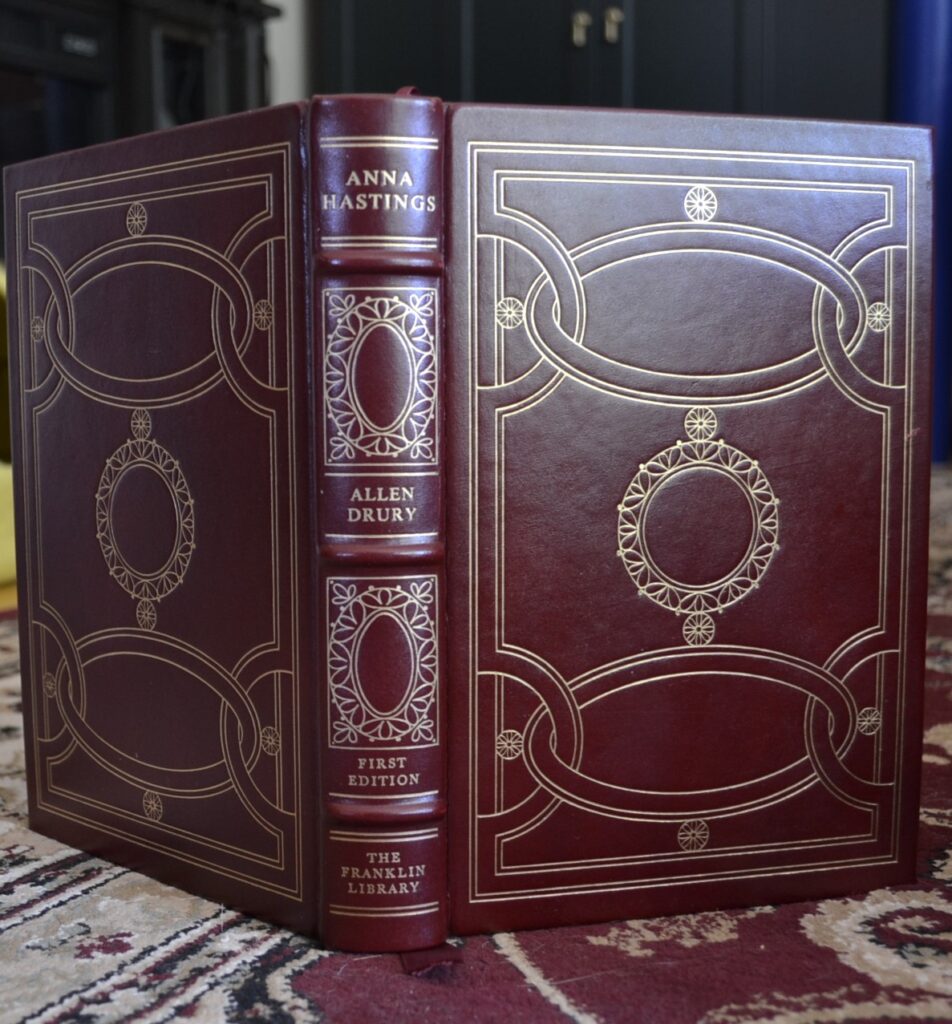

However, sometimes when I’m in an antiquarian bookstore, I tend to let myself be guided more by intuition and book design since I don’t have the luxury of prior research. And I don’t particularly want to sit on the floor and google every title I find interesting. Most of the time, these selections pan out and I’m at least treated to a read that maybe I wouldn’t choose again but still has some value.

But sometimes I end up with a very fancy book that I absolutely loathed. These books I usually donate, but I decided that I’ll put them to use before I do so by reviewing them first.

Purely Spite

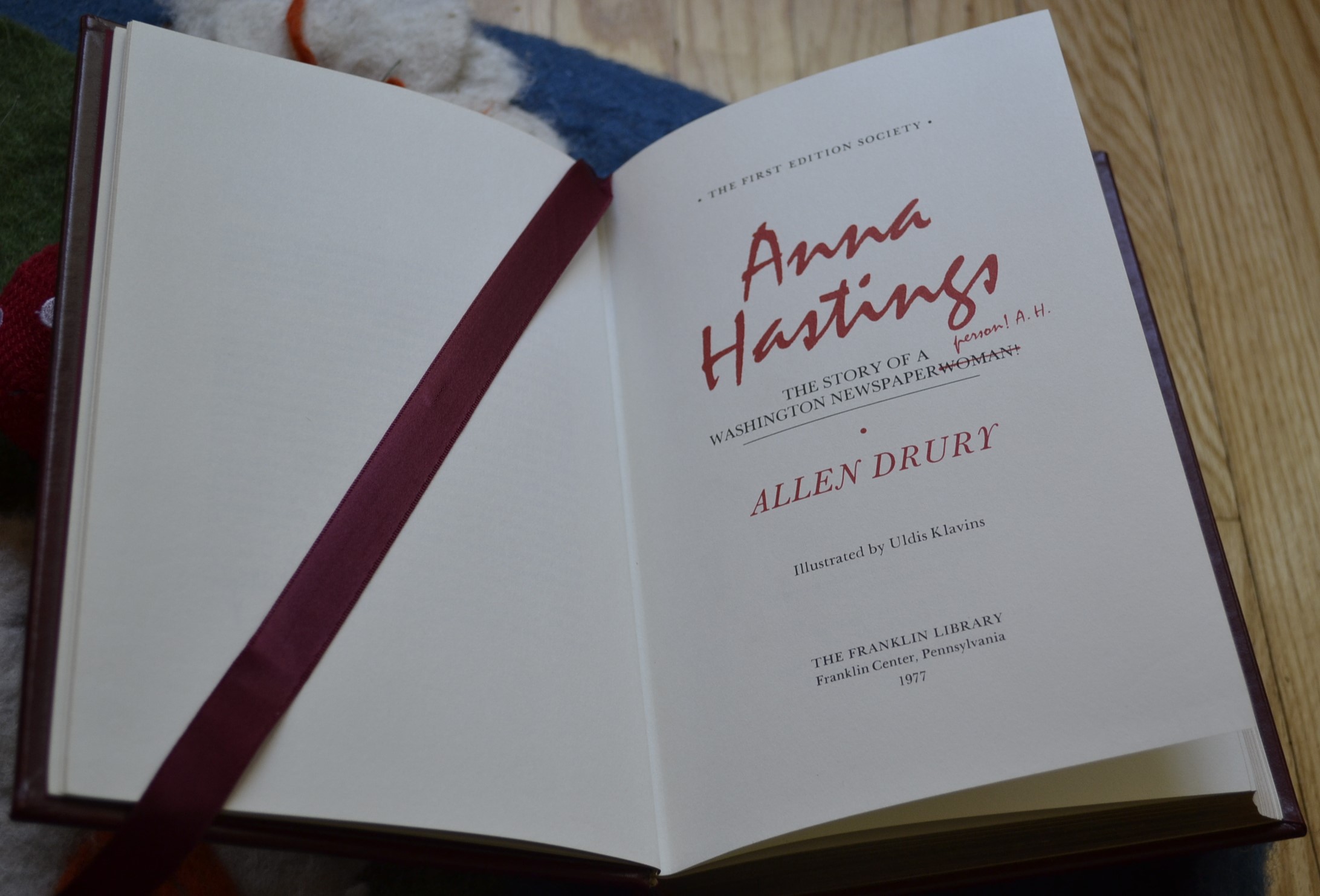

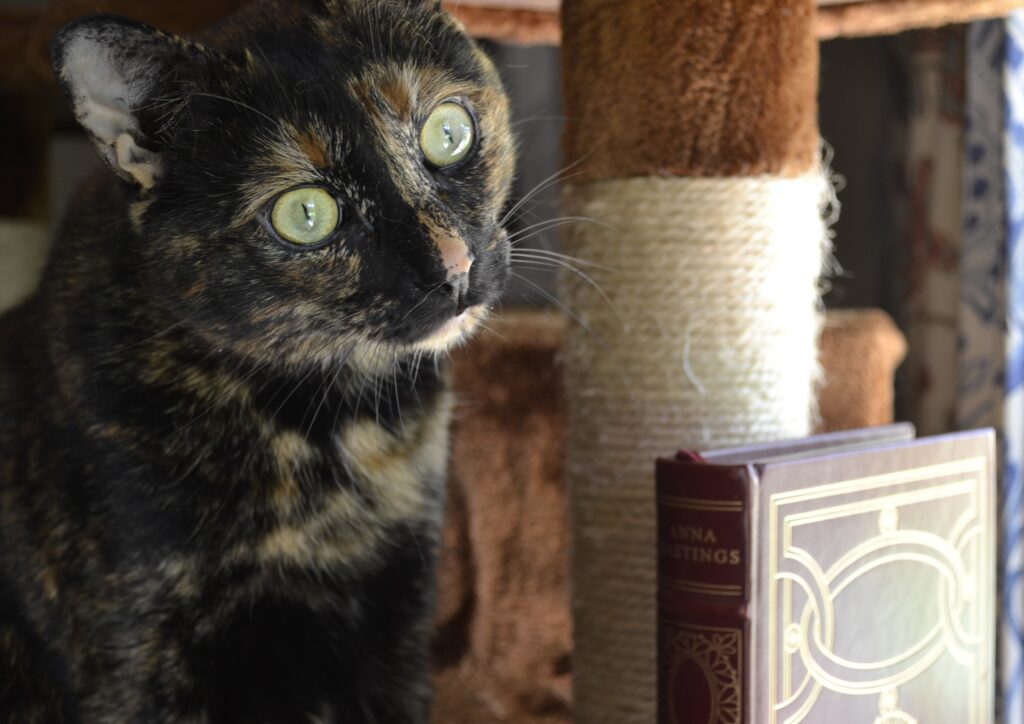

Allen Drury’s Anna Hastings was published in 1977, and it takes its plot and structure in the form of a fake exposé biography of a female journalist that makes her way to the top and promptly discovers that she’s there alone. Seems simple? Well, in essence it is. During the late 1970s, there was continually more discussion about the role of women in society as more and more chose to pursue careers in male-dominated fields and struggled to define themselves by more than motherhood or marriage. A lot of men had a problem with this. After reading this book, it becomes quite obvious that Drury was probably one of these men.

While Drury (and the character in the novel that is his stand-in) keep insisting that Anna Hastings is an effective journalist and that women do have value in the workplace, the character of Hastings is so utterly repugnant. She’s the cold, ruthless career woman that loves nothing but her job and, because she loves her job, she destroys everything around her. She uses sex to get ahead. She uses her looks. She uses everyone around her. She is a black hole of a human being. And somehow Drury thinks this is a positive depiction of women in the workplace.

It actually is a mean-spirited and sexist statement about women in traditionally male roles, positing that when women are working, they are inherently not fulfilling their assigned role in society and apparently everything crumbles around them. Even things that are not in any way Hastings’ fault — her husband’s infidelity and her children’s participation in 70s counterculture — are entirely blamed on Hastings. Because she’s not in the home. It’s so horrifying.

Body Shaming

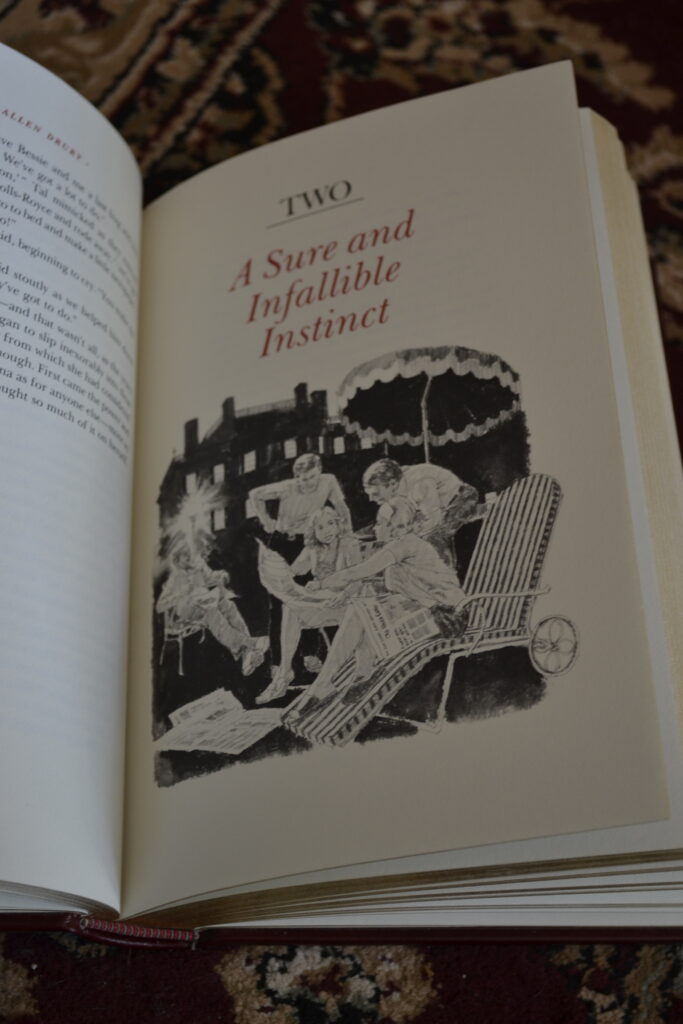

One of the more cringingly awful aspects of the novel is the character of Bessie Rovere. Drury uses Rovere to serve as a sharp contrast for Hastings, and thusly she is given all of the characteristics that Drury and his contemporaries have decided are more traditionally feminine. She is soft-hearted, writes society pages and hates politics, is shamelessly devoted to Hastings, and has no ghost of ambition at all. She cries all the time. She is sensitive. She represents what some pushed as the ‘acceptable’ woman in the office. The idea that it was okay for women to work as long as they still acted like ‘women’.

As if that wasn’t awful enough, Drury calls her fat every time she enters a scene. He marks time by how much weight she has gained. It is her primary characteristic. Her appearance is constantly ridiculed. This character is a punching bag for the writer, who seems to intensely dislike women. The writing is just so mean and petty. Books from their era often stray into the realm of fat-shaming, but this is by far the worst offender that I have ever seen.

As a bonus? Uldis Klavins’ illustrations show us a Rovere that is a completely normal weight. In fact, she is pretty much indistinguishable from Hastings in most of the full-page plates. Aggravating. Absolutely aggravating.

Is This Feminism?

It’s utterly rage-inducing to think that this book actually sold copies way back in 1977 on the back of being feminist. There is absolutely nothing feminist about it. Not at all. Not remotely. In fact, I would say Drury is more interested in keeping women in the tidy cage that the 1950s made for them and far out of the workplace — judging by this book alone.

Drury did have a history as a political correspondent, and a writer of political and historical fiction novels. He knew journalism, and he knew that journalists and journalism were changing to include more opinions, more diverse voices, and more critical thinking that did not necessarily agree with the powers that be. Anna Hastings was a book that attempted to address this, but all it did was reveal a very definite bias and a longing for the bad old days.

It’s important when reading all literature, but it’s especially important when you are presented with a work that is labelled as feminist or forward-thinking that you consider the writer as well as the context they were writing in — and what their ‘own voice’ may be, including the biases that voice might carry with it. There are a lot of things that were labelled one way decades ago, but now are laughably outside of that label.

Part Two Next Week!

On my last run to the antiquarian bookstore, I actually ended up with not one but two fancy books I didn’t like (and many other books I did like, but that’s neither here nor there). Stay tuned next week for part two: Fancy-Books-I-Don’t-Like Electric Boogaloo.